NJ high school students turned civil rights lesson into federal law

NJ teens that tweeted their civil rights bill into law, will travel to Washington to lobby for funding

HIGHTSTOWN, N.J. -- For three years, teens at Hightstown High School worked to turn a school project into federal law. They researched endlessly, drafted legislation and even tweeted to President Trump.

Last month, Trump signed the bill they helped create into law -- and these teenagers became an important part of history. The bill set up a review board to examine unsealed and unredacted records of civil rights crimes.

The effort started when they began studying the civil rights era during an AP government class.

They began by filing FIOA request on old cases and then waited for a response. They grew frustrated waiting for answers and they quickly began imagining what the victims' families must go through when their questions go unanswered for years, even decades.

“Many people died before they could even get justice and that's because of a failure to disclose information of records,” said teacher Stu Wexler.

Unsatisfied with the process, the teens began to mobilize.

For three years teens at Hightstown High had researched, drafted, and even tweeted to the President to turn their class lesson into federal law. The AP government class, studying the Civil Rights era, drafted a bill that would create a review board to examine unsealed and unredacted records of civil rights crimes.

“The information is out there it’s sitting out there, it’s just not available to these people," said high school senior Caitlin Yang. "And I really just felt like they needed to know. I know if it was me, I’d want to know.”

They learned of the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, which collects records at the National Archives from the assassination. This provided a model for the legislation they wanted.

TRUMP BOASTED HE'D OPEN ALL JFK FILES, BUT NOW SAYS HE CAN'T

Students drafted and lobbied for the bill's approval.

They traveled to Capitol Hill to pass out folders. They eventually got the support of Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill., who introduced the bill in 2017.

During the course of a year, Sens. Doug Jones of Alabama, a Democrat, and Ted Cruz of Texas, a Republican, signed on. And on January 8, just hours before it would expire in a pocket veto, President Trump signed the bill into law.

“This is something way outside of the normal scope," Wexler said. "No teacher, class, set of students, have ever done this before successfully in the country.”

Former student Oslene Johnson, who was a part of the original class that began drafting the bill but is now a sophomore in college, said everyone was determined to make a difference.

EMMETT TILL KILLING REOPENED BY GOVERNMENT OVER 'NEW INFORMATION'

"The thing that has always motivated me and will continue to motivate me and my classmates are the families who have lived with questions about what happened to their loved ones 50 years or more ago,” she said.

With one victory down, the young lawmakers say they aren’t finished -- yet.

The group plans to take on Congress again, this time hoping to gain funding for the bill.

“We are not giving up and we are looking to work with those in power to protect the spirit of this law,” Johnson said.

The students, many who are not old enough to vote, say they don’t plan on giving up until the families who have gone decades without answers have a sense of closure.

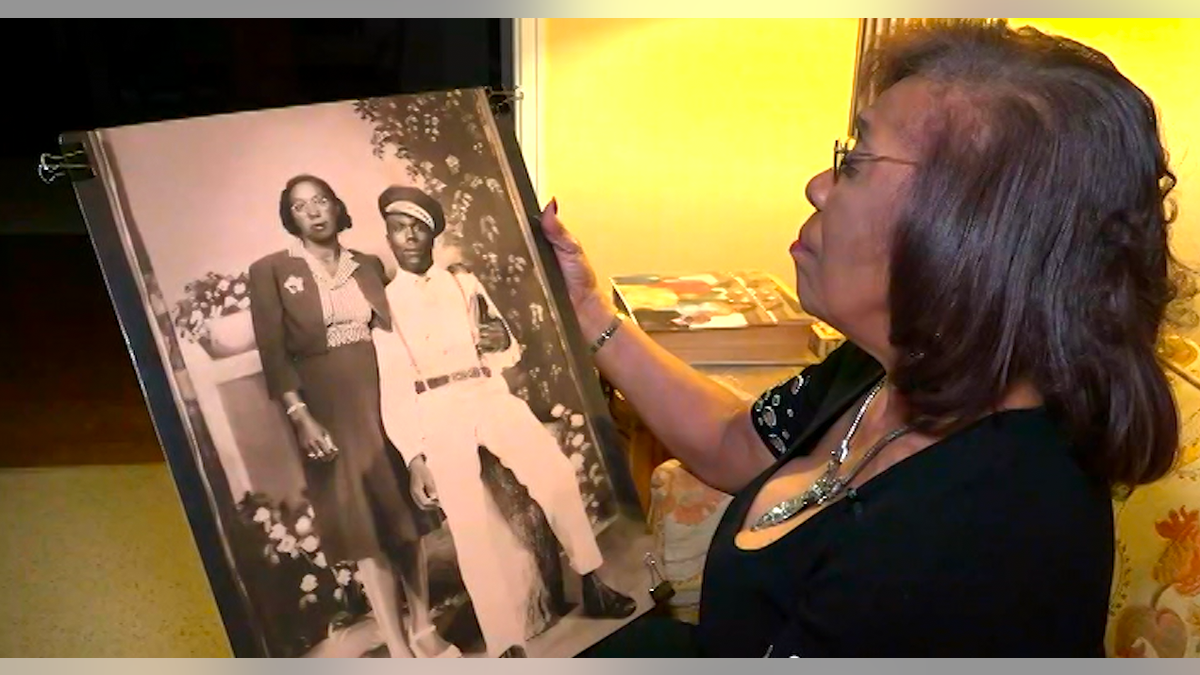

Families like Josephine McCall, whose father was murdered in Alabama in 1947.

Josephine McCall's father was murdered in Alabama in 1947.

“He had a farm that employed about 40 to 60 people, a store, and the trucking business,” said McCall, “[I guess] he was too prosperous as a Negro farmer.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

McCall believes her father was lynched because of the families perceived wealth. But for nearly half her lifetime, she went without any answers.

“I was 35 years old when I read an article clipping that detailed my father’s murder,” said McCall. “He was shot six times, the article said.”

McCall is not alone in her fight. Northeastern University professor Margaret Burnham believes the students’ efforts are encouraging for not only families but also historical institutions -- and the nation.

“This is important and will help to correct the history of Congress's failure to meet its obligations to provide security to the victims of racial violence in the Deep South,” she said.