Conner's close friends say he never talked about the war, but a box full of medals and old records brought his story back to life. (Courtesy: Conner family)

The true story of Garlin Murl Conner’s heroism in the face of a Nazi onslaught might have gone to the grave with the soft-spoken Kentucky farmer if not for a chance phone call from another military man trying to piece together the last days of his uncle’s life.

That call -- and the heartbreaking developments that followed -- left Richard Chilton with no answers, but gave the tenacious former Green Beret a cause: Seeing that Conner, who on one day in 1945 killed 50 German soldiers and saved his storied battalion on the front lines in France, is recognized with the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for acts of valor above and beyond the call of duty.

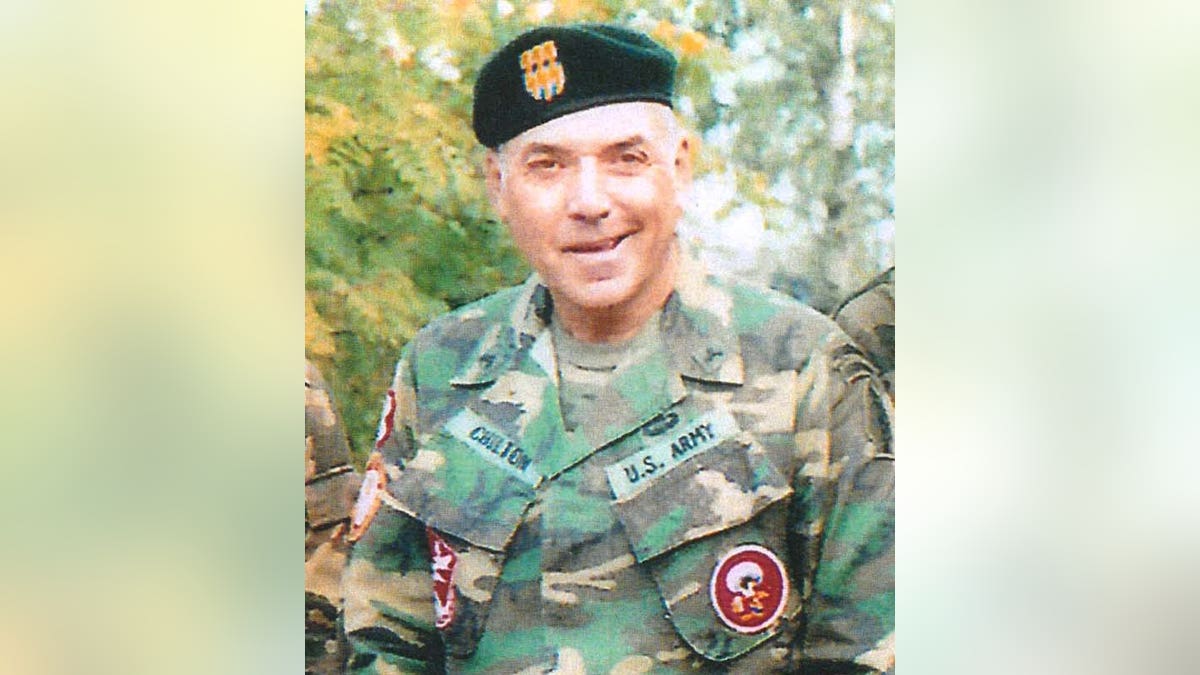

“This man may have been the greatest soldier of our time,” said Chilton, whose bid to get Conner the Medal of Honor began in 1998, wended its way through a series of military panels and federal courts, and now stands closer than ever to fruition. “I owe it to him to fight like hell to make damn sure the Army gives him what he earned.”

“This man may have been the greatest soldier of our time. I owe it to him to fight like hell to make damn sure the Army gives him what he earned.”

After a series of denials that led Chilton and advocates including retired Air Force Col. Dennis Shepherd, an attorney for the Kentucky Department of Veterans Affairs, to turn to the federal courts for help, the effort took a leap forward last week. The Army Board for Correction of Military Records bucked its own staff and ignored a federal judge’s ruling that the statute of limitations barred consideration and recommended Conner for the award, which can only be bestowed by the president.

The bravery of Conner, who died in 1998 at the age of 79, is well-documented. The first lieutenant, who was wounded seven times, earned an incredible four Silver Stars, four Bronze Stars, seven Purple Hearts and the Distinguished Service Cross for his World War II heroism. But it was what he did on Jan. 24, 1945, near Houssen, France, that elevated his courage to mythical status.

And the story would have remained in obscurity, alive only in Conner’s mind and packed away in a cardboard box near his Albany, Ky., home, were it not for Chilton.

Lt. General Alexander M. Patch awards Garlin Murl Conner the Distinguished Service Cross, Feb. 10, 1945 for extraordinary heroism in action.

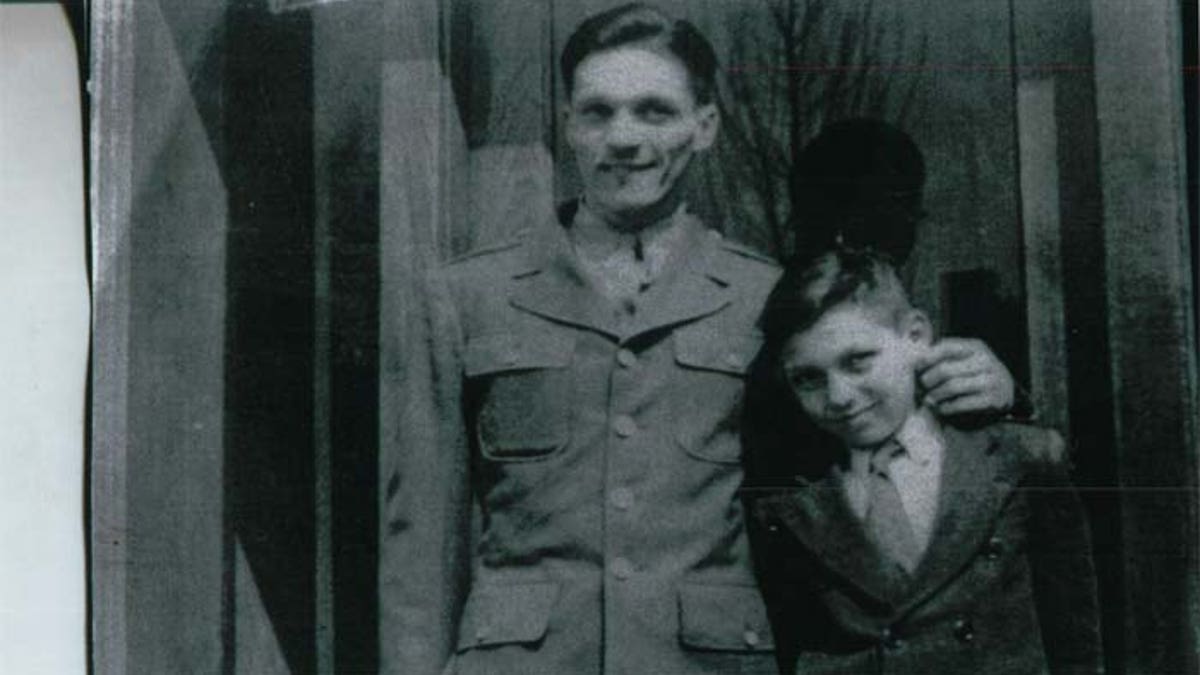

Chilton, a veteran of the Korean War who later trained Israeli fighters during the Gulf War, wanted to learn more about his uncle, Army Pfc. Gordon Wesley Roberts. All he knew was that the brave man he remembered from his boyhood had served in the 3rd Infantry Division and had never made it home from World War II. It was 1995, and Chilton, now 82, started tracking down men from the division, which included movie star Audie Murphy – himself a Medal of Honor recipient – and which lost more men than any other in the war.

“I’d called about 200 men, and no one really was able to tell me much about my uncle,” Chilton recalled. “I was ready to give up but I tried one more. I left a message with Garlin Murl Conner.”

A few days later, Chilton got a cryptic message on his answering machine.

The Medal of Honor is the military's highest honor, and is awarded by the Commander-in-Chief.

“I knew your uncle,” Conner said. “I was with him the night he died. He died from small arms fire. More to follow.”

But that was the last Chilton heard from Conner. When he finally mailed a letter to him, Conner’s wife, Pauline, wrote back to say her husband had had a stroke days later and could no longer speak. Chilton, who lives in Genoa City, Wis., drove more than 500 miles to Conner’s home in the desperate hope that a face-to-face meeting might yield information.

But it did not. As a dejected Chilton was walking out the door of the Conner home, Pauline suggested he look through her husband’s records. Maybe there would be a clue about his uncle there, she said. She emerged from a back room with a box full of medals, commendations, yellowed newspaper clippings and faded photographs.

Chilton found nothing on his uncle, but his amazement grew as he spent the next few hours digging through the box.

“I discovered the most decorated soldier I’d ever heard of,” Chilton said. “I was blown away. I’ve never seen a man with four Silver Stars.”

Chilton, a Green Beret who served in the Korean War, knew a brave soldier when he saw one. (Courtesy: Richard Chilton)

Through the pictures, medals and testimony of Conner’s superior officers, including legendary Maj. Gen. Lloyd Ramsey, the story of Conner’s heroic actions more than 50 years earlier in France came back to life. Earlier that day, Conner, who had been badly wounded in the hip, sneaked away from a field hospital and made his way back to his unit’s camp. His commanding officer was seeking a volunteer for a suicide mission: Run 400 yards directly toward the enemy while unreeling telephone wire all the way to trenches on the front line. From that point, the volunteer would be able to call in targeting coordinates for mortar fire.

Conner's story was revealed when Chilton, shown here as a boy with his uncle, Army Pfc. Gordon Wesley Roberts, sought to find out what happened to his relative. (Courtesy: Richard Chilton)

Conner grabbed the spool of wire and took off amid intense enemy fire. He made it to the ditch, where he stayed in contact with his unit for three hours in near-zero-degree weather as a ferocious onslaught of German tanks and infantry bore down on him.

“My God, he held off 600 Germans and six tanks coming right at him,” Chilton marveled. “When they got too close, his commander told him to vacate and instead, he says, ‘Blanket my position.’”

The request meant Conner was calling for artillery strikes as he was being overrun, risking his life in order to draw friendly fire that would take out the enemy, too.

Circumstances conspired to thwart Chilton’s initial effort to have Conner awarded the Medal of Honor, which 471 men received for their efforts in World War II. His commander did not fill out necessary paperwork, an oversight he later apologized for. Records, which included testimony from fellow soldiers, were lost with millions of others in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. But perhaps most of all, Conner never told his story.

Chilton's application in 1997 on behalf of Conner was rejected. An appeal supported by the Kentucky Department of Veterans Affairs three years later was similarly nixed. But Shepherd and his team, with the help of Rep. Ed Whitfield, R-Ky., managed to find duplicate documents in which soldiers attested to Conner’s exploits in the National Archives.

Shepherd’s team took those papers and the recommendation of Ramsey, now 96, to federal court in 2013, seeking to have the Army re-examine the application. District Judge Thomas Russell rejected the motion, noting the seven-year Statute of Limitations had passed since the last appeal. But his reluctance was clear in his decision, in which he said a technicality should not diminish Conner’s “extraordinary courage and patriotic service.” Shepherd said Russell’s words helped set the table for an appeal to the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.

In a dramatic proceeding in the Cincinnati court, the three-judge panel heard all the testimony about Conner’s actions, and the courtroom was stunned when Assistant U.S. Attorney Candace Hill told the judges her own father served with Conner.

For Shepherd and Chilton, the difficult part is getting someone to listen to the evidence.

“Anytime I’ve been able to put the facts regarding Garlin Conner in front of someone, we get results,” said Shepherd. “As soon as these judges saw what he had done that day, they didn’t care about the statute of limitations.”

The 6th Circuit ordered both parties into mediation, which led to last week’s ruling by the Army Board for Correction of Military Records. That recommendation will likely carry weight with the Senior Army Decorations Board, though it could take “several months” for a decision.

If the decorations board recommends the award, the Senate Armed Services Committee takes up the case and makes its own recommendation to the president.

If the words written by Ramsey, who went on to serve in Korea and Vietnam, where he commanded the Americal Division, when Conner’s bravery was fresh in his mind, hold sway, Conner’s ailing wife and numerous supporters could yet help repay an American hero.

"I just sent one of my officers home,” Ramsey, then a lieutenant colonel, wrote to a colleague in Kentucky in 1945, when Conner was discharged. “I'm really proud of Lt. Conner. He probably will call you and, if he does, he may not sound like a soldier, will sound like any good old country boy, but, to my way of seeing, he's one of the outstanding soldiers of this war, if not THE outstanding."