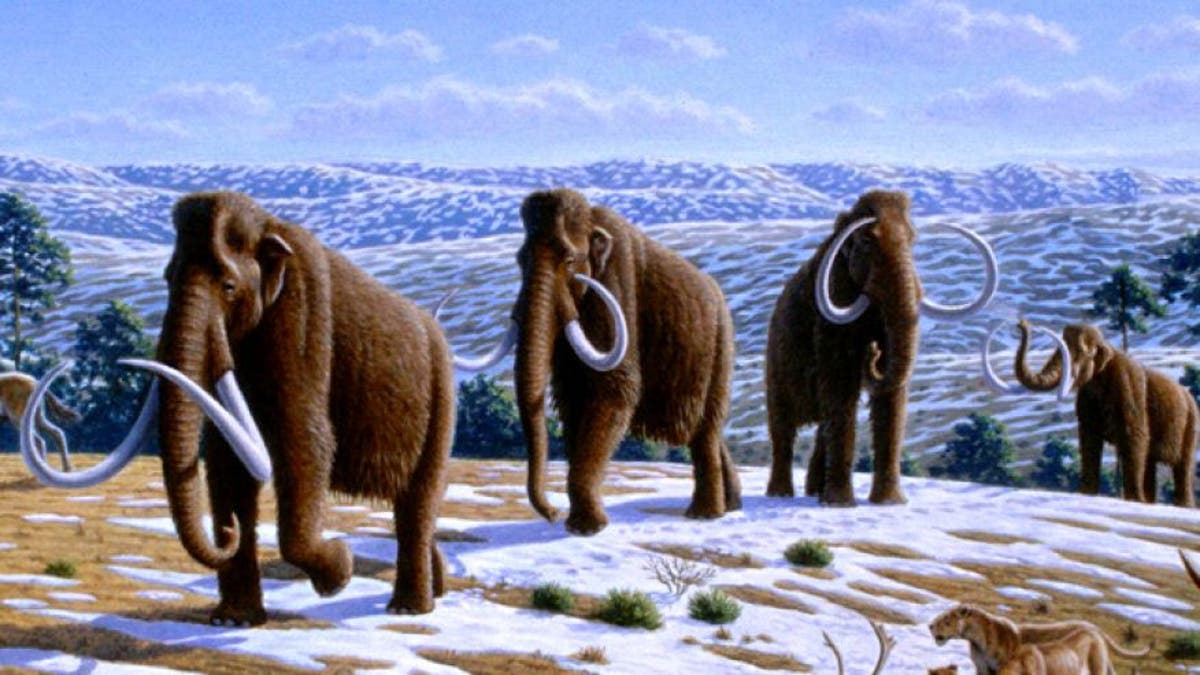

An artist's illustration depicts a herd of woolly mammoths. (Mauricio Anton/PLoS)

The idea of bringing extinct animals back to life continues to reside in the realm of science fiction. But scientists have taken a small step closer to that goal, by inserting the DNA of a woolly mammoth into lab-grown elephant cells.

Harvard geneticist George Church and his colleagues used a gene-editing technique known as CRISPR to insert mammoth genes for small ears, subcutaneous fat, and hair length and color into the DNA of elephant skin cells. The work has not yet been published in a scientific journal, and has yet to be reviewed by peers in the field.

Woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) have been extinct for millennia, with the last of the species dying out about 3,600 years ago. But scientists say it may be possible to bring these and other species back from the grave, through a process known as de-extinction. [Photos: 6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life]

But we won't be seeing woolly mammoths prancing around anytime soon, "because there is more work to do," Church told U.K.'s The Times, according to Popular Science. "But we plan to do so," Church added.

Splicing mammoth DNA into elephant cells is only the first step in a lengthy process, Church said. Next, they need to find a way to turn the hybrid cells into specialized tissues, to see if they produce the right traits. For instance, the researchers need to make sure the mammoth genes produce hair of the right color and texture.

After that, the team plans to grow the hybrid cells in an artificial womb; scientists and animal-rights advocates have deemed it unethical to grow them in a living elephant's womb.

If the researchers can get these hybrid mammoth-elephants to survive, they hope to engineer an elephant that can survive in cold climates, where it should face fewer threats from humans. Only once the team can get these hybrid creatures to survive will they incorporate more mammoth DNA into the elephant's genome, with the ultimate goal of reviving the ancient beasts.

But woolly mammoths aren't the only candidates for de-extinction. In 2003, scientists briefly revived the Pyrenean ibex, which went extinct in 2000, by cloning a frozen tissue sample of the goat. However, after being born, the clone survived for just 7 minutes.

Several years ago, a group of researchers took DNA from a 100-year-old Tasmanian tiger specimen at a museum in Melbourne, Australia, and inserted it into mouse embryos, showing the genes were functional.

And Church himself has been working on trying to bring back the passenger pigeon, a bird whose flocks once filled the skies of North America but went extinct in the early 20th century. The researchers extracted about 1 billion DNA "letters" from a 100-year-old museum specimen, and are attempting to splice them into the DNA of a common rock pigeon.

But even if these efforts succeed, they pose some ethical challenges.

For example, the ability to revive once-extinct creatures in a lab could encourage support for the destruction of natural habitats, Stuart Pimm, a conservation ecologist at Duke University, told Live Science in August 2013.

"It totally ignores the very practical realities of what conservation is about," Pimm said.

Other scientists have been cautiously accepting of the idea. Stanley Temple, an ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison told Live Science in August 2013, "We can use some of these techniques to actually help endangered species improve their long-term viability."

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Skin and Bones: Inside Baby Mammoths

- Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.