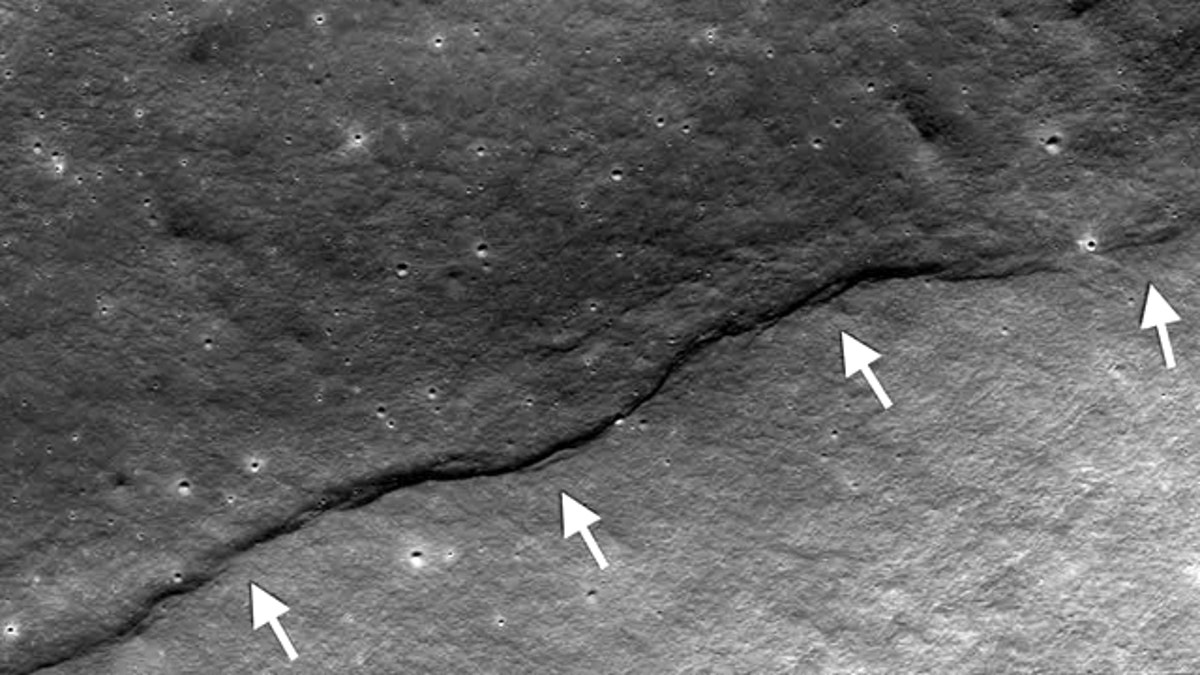

By analyzing new photos of faults such as this on the moon, scientists have concluded that our nearest heavenly body is shrinking. (NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University/Smithsonian)

The moon is shrinking ever so slightly, but there is no cause for alarm, according to a new study that has discovered a clutch of previously unseen faults on the lunar surface from photos taken by a NASA probe.

In all, 14 previously undetected small thrust faults -- the physical markers of contraction on the lunar surface -- were found to be globally distributed around the moon in thousands of photos returned by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. [10 Cool New Moon Discoveries]

These fault structures -- called lobate scarps -- are among the youngest landforms on the moon. Their distribution across the lunar surface (as opposed to regional distribution) suggests that cooling in the moon's interior is the likely cause of the contraction, or shrinkage, said study leader Thomas Watters, a scientist with the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

The surface is pushed together by internal forces," Watters told SPACE.com. "When it breaks, it literally thrusts material upward because the surface is contracting. That contraction, we think, is coming from internal cooling of the moon. We now know that's a global process, so it means the moon is shrinking globally -- very likely because it is continuing to cool."

The research is detailed in the Aug. 20 issue of the journal Science.

Surprise moon finding

Lobate scarps were first recognized in photographs taken of the moon's equatorial region by panoramic cameras flown on the Apollo 15, 16 and 17 missions in the early 1970s.

"Since the Apollo missions were designed to land men on the moon, coverage from the Apollo photography was very limited, and only in the portion of the equatorial zone," Watters said.

Photos from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera have now revealed how widely distributed these landforms actually are on the lunar surface.

"We found that these landforms occur not only elsewhere in the equatorial zone, but also at high latitudes," Watters explained. "At least half of the 14 that we report on were at latitudes higher than 60 degrees. Several of them are near the lunar poles."

He expects that as the LRO mission continues researchers will discover even more of these structures.

"The ultra-high resolution images from the Narrow Angle Cameras are changing our view of the moon," said study co-author Mark Robinson, who is the principal investigator of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera at Arizona State University. "We've not only detected many previously unknown lunar scarps, we're seeing much greater detail on the scarps identified in the Apollo photographs."

The incredible shrinking moon

According to the study, there has been about 328 feet (100 meters) of change in the moon's radius over the course of about 1 billion years, said Watters.

"This is a very small amount," he said. "I don't want to give the impression that the moon is dramatically shrinking away."

Watters was able to approximate the age of the fault scarps by comparing them to other geological landforms, and using a method of dating that examines the presence of impact craters on the structures themselves.

He found that the lobate scarps were small and narrow -- the largest ones being no more than 6.2 miles (10 km) in length. Their pristine appearance was also a good indication of their young age.

"We don't see any impact craters superimposed on them," Watters said. "They have not been partially obliterated by impact craters that have hit them, so this tells us that they are very young. Features of this size would not be expected to survive very long un-degraded on the lunar surface, simply because they would typically be obliterated by impact."

Since the scarps were undestroyed and in good condition, Watters was able to assign an upper limit for the age of the landforms.

"They can't be any older than a billion years, which is pretty recent in lunar history," Watters said. "They are so un-degraded and pristine looking that they could be very much younger than that. One of the intriguing prospects is that these faults could be very recent, so we can't exclude the possibility that the moon is tectonically active today."

Will the moon keep shrinking?

If the moon's interior is still cooling, it would provide evidence that the moon is still geologically alive and active -- which has been an area of study since seismographs first detected moon quakes during the Apollo era.

"We knew things were going on inside the moon, but now one of the questions is whether the lunar seismic activity that was recorded is possibly connected with some of these young thrust faults," Watters said.

Watters is now hoping to use LRO's capabilities to create a global, high-resolution image map of the moon, which could help researchers find more of these lobate scarps. But, since the Narrow Angle Cameras on board LRO only capture very small portions of the lunar surface per image, building the map will take time.

In the meantime, Watters is quick to stress that even if the moon is continuing to shrink, there is no reason to be alarmed.

"Over a billion years, a 100-meter change in the radius is not very much," Watters said. "The moon is not shrinking so much that you would ever detect it, and it's not going to shrink away. There are other planets, like Mercury, that have a lot more contraction."

Lobate scarps have previously been found on Mercury, and the largest one is over 620 miles (1,000 km) in length.

"Mercury is an example of a much greater radial-contracting body," Watters said. "This is due to the same process of interior cooling as on the moon, but it's happening on the moon in a much smaller way."

Copyright © 2010 Space.com. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.