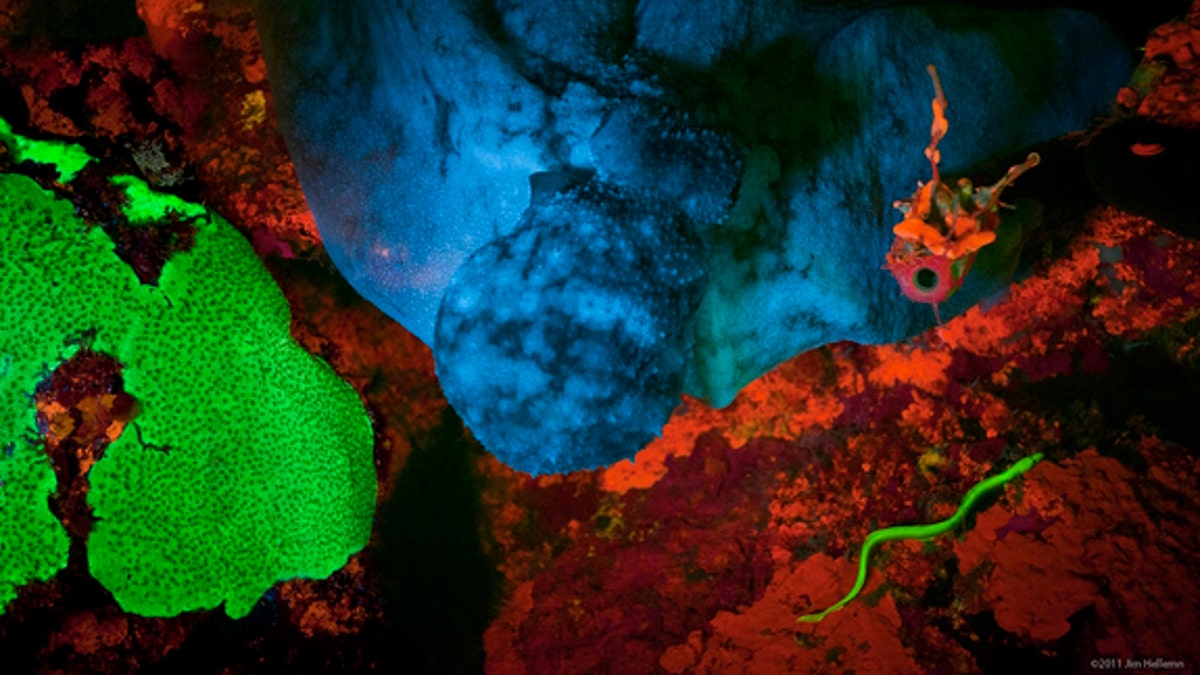

This biofluorescent green eel (lower right corner) surprised scuba-diving scientists, and prompted them to study its glowing proteins. (Copyright Jim Hellemn)

When scuba-diving scientists serendipitously spotted a glowing green eel in January 2011, they had no idea what caused it to light up like a brilliant neon sign.

But now, after hours spent studying the fluorescent proteins of two eels, the researchers have solved the mystery. These proteins, found throughout the eels' muscle and skin tissues, actually originated in vertebrate brains more than 300 million years ago, a new study finds.

"It started as a brain protein and then became this fluorescent protein in muscle," said study lead researcher David Gruber, an associate professor of biology at Baruch College in New York City. [See Photos of the Glowing Green Eels]

Once the protein made its switch from a neural to a fluorescent protein, it spread like crazy throughout the eel population. Natural selection favored it so much, it's likely fluorescence plays a crucial role in the eel world, Gruber said.

For instance, maybe it helps them spawn the next generation, he said. One anecdotal report of such spawning describes a "big, green fluorescent mating event" with a dozens of eels getting it on under a full moon in Indonesia, Gruber said. Typically, these eels are reclusive and shy, spending most of their lives hiding in the holes and crevasses around coral reefs and sea grass beds. But maybe the moonlight stimulates their fluorescent proteins, making them more visible to potential mates, he said.

"We're hoping to witness one of these spawning events to see what they're doing," Gruber told Live Science. Moreover, the fluorescence may also play a role in eel communication, predator avoidance or even prey attraction, like the anglerfish's glowing 'fishing rod,' which lures in fishy meals, according to Gruber.

Eel expedition

After seeing the stunning 2011 photo, the researchers wanted to learn more about the little green eel. They found two eels (Kaupichthys hyoproroides and another species of Kaupichthys) during an expedition in the Bahamas, and brought both back to Gruber's lab in New York City.

K. hyoproroides is small — no longer than two human fingers — about 9.8 inches (250 millimeters) long, Gruber said. It's likely that the other eel is a new species in the Kaupichthys genus, he added, but the specimen wasn't in good enough condition to describe it, he said.

A tissue analysis showed fluorescence throughout the eels' muscle and skin. But a protein analysis didn't yield any green fluorescent protein (GFP) — a protein famously identified in a hydrozoan jellyfish in 1962. Nor did it match fluorescent proteins found in other glowing sea creatures, such as some fish and sharks, Gruber said.

Instead, it bore a resemblance to a fluorescent protein found in Anguilla japonica, an eel species used in sushi whose proteins can fluoresce a weak green color when bound to bilirubin. (Bilirubin is a yellow waste product that comes from broken-down red blood cells. People with jaundice have yellowish skin and eyes because of increased levels of bilirubin in their blood.)

The protein from the Kaupichthys eels also needed bilirubin to fluoresce, but a key part of the chemical makeup of this protein was different from the sushi eel's proteins. "It turns out that every one of these new proteins that has this key little region in it has the ability to glow, and glow very bright," Gruber said. [Images: Fish Secretly Glow Vibrant Colors]

Intrigued, Gruber and his colleagues teamed up with Rob DeSalle, a curator with the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. DeSalle is an expert in evolutionary biology, and determined that the eels' fluorescent protein is a newly identified family of fluorescent proteins, Gruber said.

DeSalle also studied the evolutionary history of the Kaupichthys protein. He saw that it was closely related to a fatty acid-binding protein found in the brain of most vertebrates. This protein likely plays a role in fatty-acid uptake, transport and metabolism in the brain, and may help young neurons migrate and establish cortical layers in the brain, DeSalle told Live Science.

However, over time this genetic code for this brain protein underwent three duplication events, meaning there were more copies of the protein available for the organism to play around with, DeSalle said. The duplicated genes for these proteins could then mutate over time, eventually leading to the fluorescent, bilirubin-binding protein that glows bright green in certain eels, the researchers said.

The study researchers didn't pinpoint when the three duplication events happened, but DeSalle estimated that the first two happened between 450 million and 300 million years ago, in the common ancestor of jawed vertebrates. The third duplication led to the creation of the newly identified fluorescent protein, DeSalle said.

There's still much to learn about fluorescent proteins, but the discovery of fluorescence in eels and other fish suggests that they played a large role in marine vertebrate evolution, said Matthew Davis, an assistant professor of biology at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota, who was not involved in the study.

"The surprising aspect of this study is that the fluorescent fatty acid-binding proteins may have impacted the evolution of this lineage of marine eels, and they also expand the suite of fluorescent probes available for experimental biology in other disciplines," Davis told Live Science in an email.

The study was published online Nov. 11 in the journal PLOS ONE.

- Bioluminescent: A Glow in the Dark Gallery

- Photos: The Freakiest-Looking Fish

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

- Glowing Eels? Sex Drives Brain Protein to Evolve Brightly | Video

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.