Fox News Flash top headlines for March 11

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

Several new forms of chlamydia-related species have been discovered "deep below the Arctic Ocean," according to a new study.

The research, published in Current Biology, notes that finding chlamydia and related bacteria (collectively known as Chlamydiae) in the region was unexpected, given its propensity for causing sexually transmitted infections in humans, animals and amoeba. The chlamydia relatives were found between 0.1 and 9.4 meters under the seafloor and with no apparent host organism.

“Finding Chlamydiae in this environment was completely unexpected, and of course begged the question what on earth were they doing there?” the study's lead author, Jennah Dharamshi, from Uppsala University in Sweden, said in a statement.

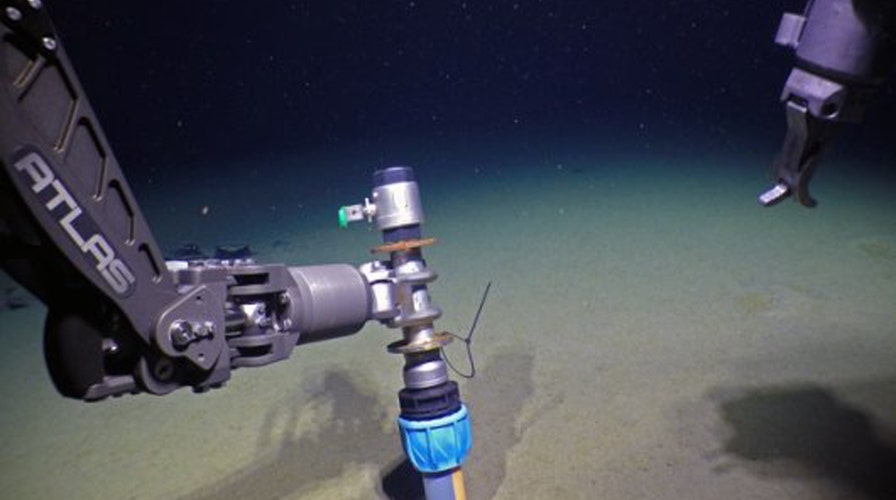

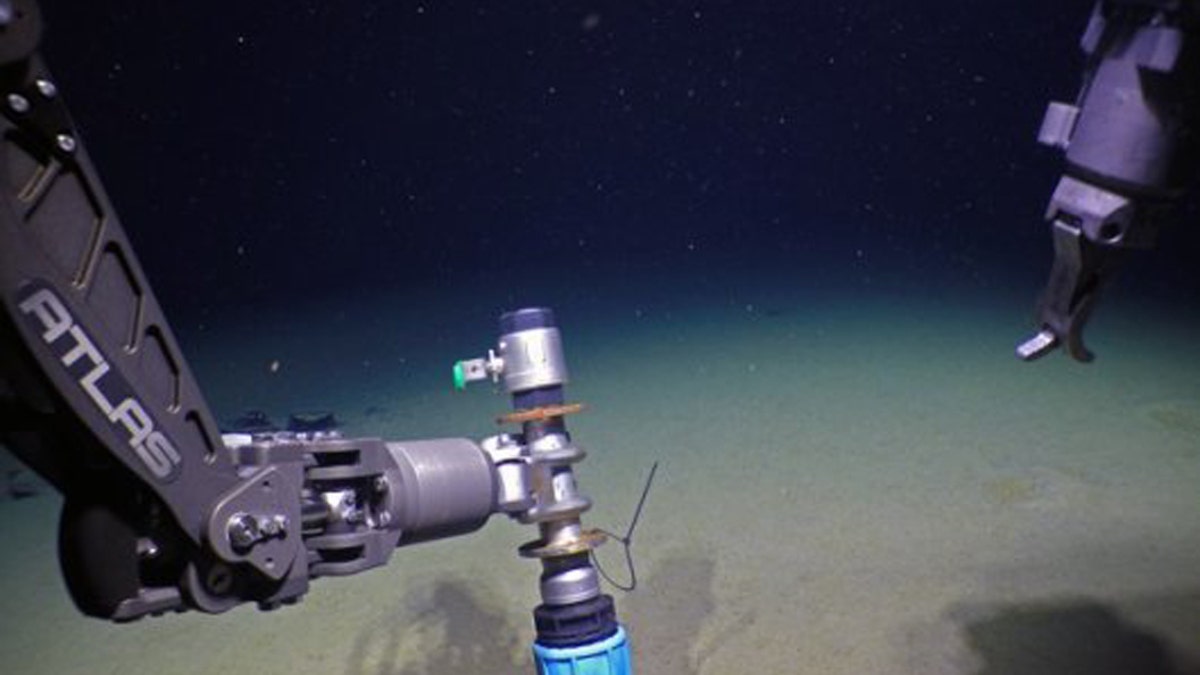

Deployment of sediment coring device in the Norwegian-Greenland sea from R/V G.O. Sars during Centre of Geobiology expedition 2015. (Credit: Wageningen University & Research)

MELTING PERMAFROST IN ARCTIC WILL HAVE $70 TRILLION IMPACT, NEW STUDY SAYS

The samples were collected from Loki’s Castle, described as "a deep-sea hydrothermal vent field located in the Arctic Ocean in-between Iceland, Norway, and Svalbard."

The experts believe they can further learn how the bacteria began to affect humans, given that there were no host organisms discovered this time around.

“Finding that Chlamydia have marine sediment relatives, has given us new insights into how chlamydial pathogens evolved,” Dharamshi explained, adding that chlamydiae has a significant impact on the ecology and the ecosystem.

“Chlamydiae have likely been missed in many prior surveys of microbial diversity,” the study's co-author, Daniel Tamarit, said. “This group of bacteria could be playing a much larger role in marine ecology than we previously thought.”

"The vast majority of life on earth is microbial, and currently most of it can’t be grown in the lab,” Thijs Ettema, professor in Microbiology at Wageningen University & Research in The Netherlands, said. “By using genomic methods, we obtained a more clear image on the diversity of life. Every time we explore a different environment, we discover groups of microbes that are new to science. This tells us just how much is still left to discover.”

In January, researchers discovered 28 never-before-seen virus groups that have been trapped in a massive glacier on the northwestern Tibetan Plateau for 15,000 years.