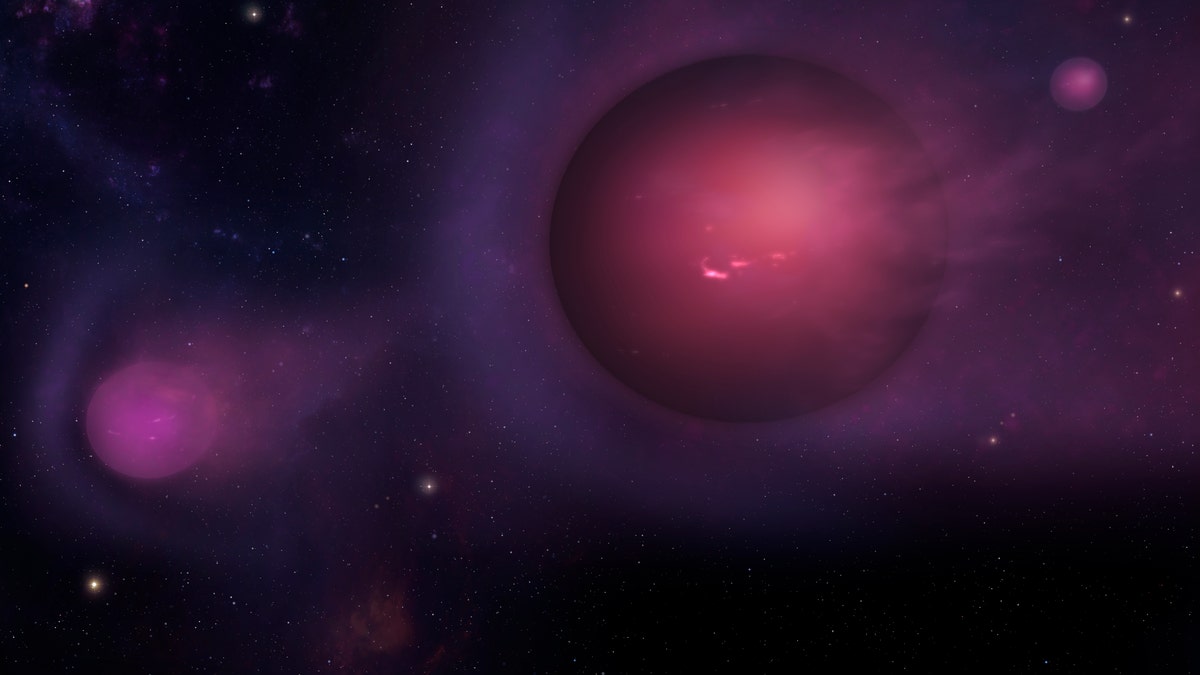

This artist's conception portrays a collection of planet-mass objects that have been flung out of the galactic center at speeds of 20 million miles per hour (Mark A. Garlick/CfA)

Apparently no one told the black hole at the center of our galaxy that it’s impolite to spit in public.

Theoretically, after a star is shredded in a tidal disruption event by the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole, the remnants of that star could form into a planet-sized gob that gets flung away at incredible speed, even out of our galaxy. These speeding objects are kind of like spitballs, according to the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

"A single shredded star can form hundreds of these planet-mass objects. We wondered: Where do they end up? How close do they come to us? We developed a computer code to answer those questions," Eden Girma, the lead researcher behind the work and an undergraduate at Harvard University, said in a statement.

The stellar leftovers could be traveling at incredible speeds: about as fast as 20 million miles per hour. And they don’t stick around in our galaxy forever— an estimated 95 percent of them zoom out of the Milky Way. This new research has calculated the amount and destinations of these theoretical cosmic spitballs, according to James Guillochon of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

“Some simulations by others have suggested that the debris from a star being disrupted by a black hole can clump up into planet-sized fragments, but those others did not calculate how many would be produced nor where they ended up,” Guillochon said in an email to FoxNews.com. “I think the most exciting aspect is that there are expected to be about 100 million of them in the Milky Way, with the closest one being a few hundred light years away.”

Galaxies like Andromeda could even be expelling these stellar spitballs, too.

“They will be very cold and very dark as they have no parent star heating them up,” Guillochon added.

A star is sucked into the black hole and torn apart “every few thousand years,” according to the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, beginning the process that forms the fragments. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, the space agency’s next-gen replacement for Hubble, could theoretically detect them.

The research is being described in a forthcoming study, Guillochon said.

Follow Rob Verger on Twitter: @robverger