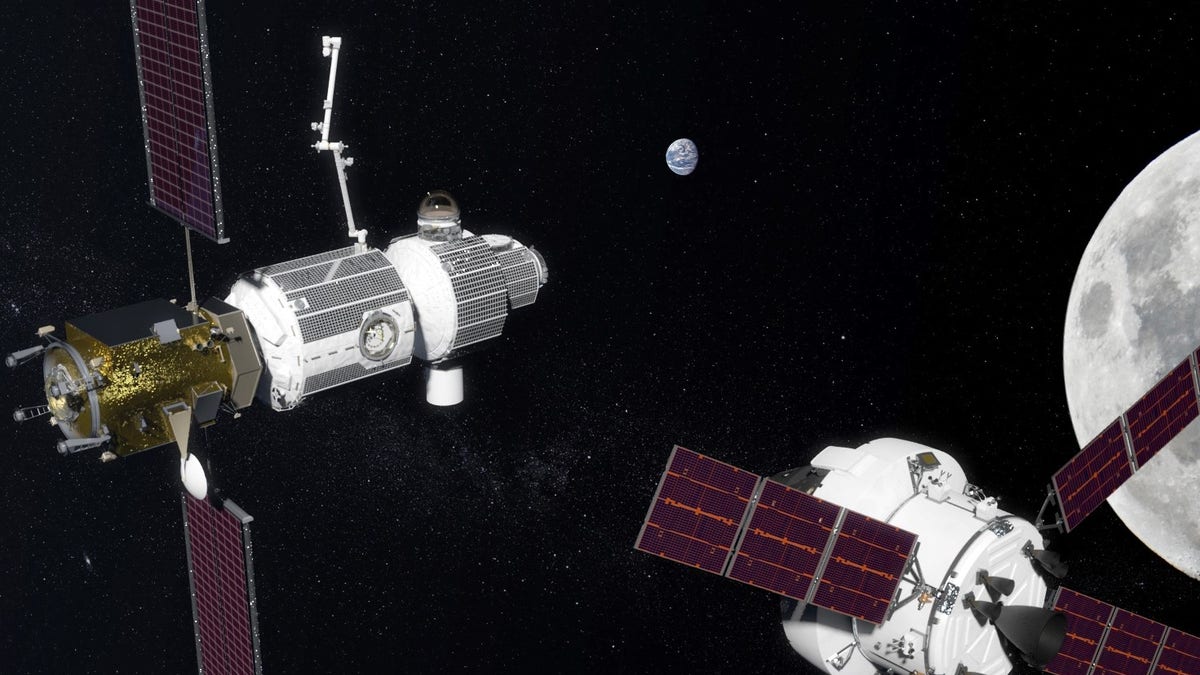

Artist’s illustration of NASA’s planned Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway outpost (left), being approached by an Orion spacecraft. (NASA)

MOFFETT FIELD, Calif. — Sending humans back to the moon won't require a big Apollo-style budget boost, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said.

During the height of the Apollo program in the mid-1960s, NASA gobbled up about 4.5 percent of the federal budget. This massive influx of resources helped the space agency make good on President John F. Kennedy's famous 1961 promise to get astronauts to the moon, and safely home to Earth again, before the end of the decade.

NASA's budget share now hovers around just 0.5 percent. But something in that range should be enough to mount crewed lunar missions in the next 10 years or so, as President Donald Trump has instructed NASA to do with his Space Policy Directive 1, Bridenstine told reporters yesterday (Aug. 30) here at NASA's Ames Research Center. [In Photos: President Trump Aims for the Moon with Space Policy Directive 1]

The key lies in not going it alone and continuing to get relatively modest but important financial bumps, he added. (Congress allocated over $20.7 billion to NASA in the 2018 omnibus spending bill — about $1.1 billion more than the agency got in the previous year's omnibus bill.)

More From Space.com

"We now have more space agencies on the surface of the planet than we've ever had before. And even countries that don't have a space agency — they have space activities, and they want to partner with us on our return to the moon," Bridenstine said in response to a question from Space.com.

"And, at the same time, we have a robust commercial marketplace of people that can provide us access that historically didn't exist," the NASA chief added. "So, between our international and commercial partners and our increased budget, I think we're going to be in good shape to accomplish the objectives of Space Policy Directive 1."

Those objectives call for a sustainable human return to the moon, rather than the transient, flags-and-footprints approach of Apollo. Establishing a permanent presence on and around the moon is an aim in itself, but it will also teach NASA and its partners the technologies and skills required to push out even farther into the solar system, to Mars and beyond, Bridenstine and other agency officials have said.

For example, water ice mined from permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles could be split into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen — prime components of rocket fuel. This propellant could then be hauled up to off-Earth depots, which could fill the tanks of spaceships bound for Mars or other distant destinations. This strategy could spur a new era of exploration, freeing humanity from the need to launch huge amounts of fuel out of Earth's substantial gravity well, space-mining advocates have stressed.

The centerpiece of NASA's crewed moon plans, at least in the short term, is the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway. This small, moon-orbiting space station will be assembled and visited with the aid of NASA's Space Launch System megarocket and Orion capsule, both of which are in development.

The Gateway will house up to four astronauts for a month or two at a time and serve as a hub for robotic and crewed exploration of the lunar surface, NASA officials have said. [Moon Base Visions: How to Build a Lunar Colony (Photos)]

The first element of the Gateway — its power and propulsion module — is scheduled to launch in 2022. Other key pieces will be lofted shortly thereafter. If all goes according to plan, astronauts could visit the outpost as early as 2024 and start making trips to the lunar surface a few years later, before the end of the 2020s, NASA officials have said.

That will be a milestone when it happens; no boots have pressed into the gray lunar dirt since the Apollo 17 astronauts departed for Earth back in 1972.

The Gateway will be compatible with a variety of vehicles, to encourage the cooperation that NASA officials deem so crucial.

"We want to have strong partnerships, not just commercially but internationally, so that we can do more than we've ever done before and build this sustainable architecture that is our direction under Space Policy Directive 1," Bridenstine said.

Indeed, NASA is encouraging the progress of private landers, such as those in development by the American companies Blue Origin, Moon Express and Astrobotic. The agency plans to buy some rides down to the lunar surface aboard such commercial craft, rather than have to build or purchase every moon lander itself.

Eventually, commercial vehicles may even ferry NASA astronauts — not just robotic payloads — from the Gateway to the moon's surface and back, Bridenstine said.

This approach is in keeping with the agency's recent push to commercialize low Earth orbit. SpaceX and Northrop Grumman already launch uncrewed cargo missions to the International Space Station for NASA, and SpaceX and Boeing both hold multibillion-dollar deals to ferry agency astronauts to and from the orbiting lab. The first crewed flights of these private astronaut taxis are scheduled to take place next year.

Originally published on Space.com.