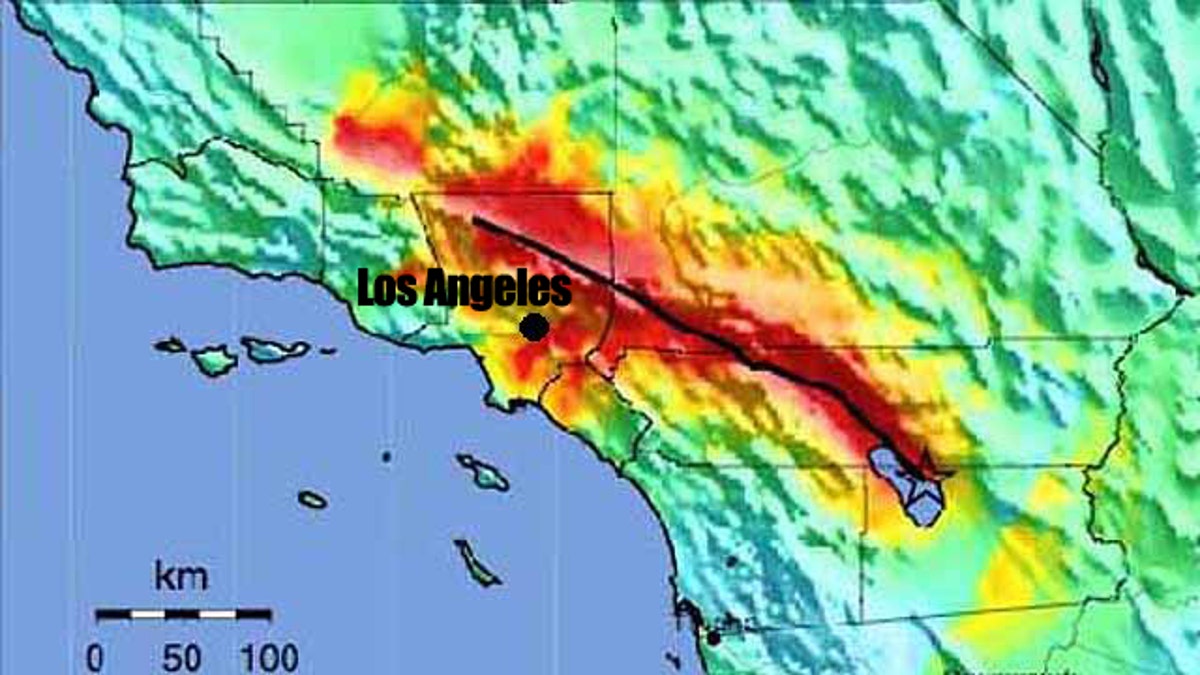

The effects of a magnitude 7.8 earthquake striking the San Andreas fault, modeled here, could cause 1,800 deaths and $213 billion of economic losses, the USGS said. Warmer colors representing areas of greater damage. (USGS)

Gigantic, devastating earthquakes have happened more frequently at the San Andreas fault than previously thought -- and we're overdue for the next one, according to a new study.

Geologists from the University of California Irvine and Arizona State University concluded that the largest quakes strike San Andreas every 45 to 144 years -- and the last big one was in 1857, over 150 years ago. While it’s possible the fault is experiencing a natural lull, the scientists think it’s more likely a major quake could happen soon.

“If you’re waiting for somebody to tell you when we’re close to the next San Andreas earthquake, just look at the data,” said UCI seismologist Lisa Grant Ludwig, principal investigator on the study.

The researchers based their analyses on the study of centuries-old charcoal samples in the Carrizo Plain portion of the fault, about 100 miles northwest of Los Angeles. The charcoal fragments during earthquakes, and radiocarbon dating pinpointed the exact time of the fragment, and therefore of the quake. Their findings were published Friday in the journal Geology.

The field data confirmed what Ludwig had long suspected: The widely accepted belief that a major earthquake happened on the fault every 250 to 400 years was inaccurate. Not all quakes were as strong as originally thought, either, but they all packed a wallop -- ranging between magnitude 6.5 and 7.9.

"People used to think you always had earthquakes similar to the 8.5 magnitude quake that struck" California in 1857, Morgan Page, a geophysicist with the United States Geological Society, told FoxNews.com. They can't all be tremendous quakes, she agreed.

Though smaller than the 1857 quake, a 7.8 magnitude quake would still cause a major disaster -- enough that California's Emergency Management agency has been planning and prepping for just such a situation.

The Great California Shakeout recently assessed the effects of such a temblor striking the southern tip of the San Andreas fault -- the Los Angeles region.

"You would see buildings collapse, you'd see people trapped, you'd see roadways collapse. You'd see widespread destruction," said Kelly Huston, assistant agency secretary for public and crisis communication at CEMA.

Still, the new data in Geology magazine is hardly conclusive, Page explained.

"Paleoseismic evidence isn't always cut and dried," she told FoxNews.com. And more evidence is needed before these theories about the frequency and strength of San Andreas quakes become accepted as fact.

"It's rather controversial. Some people support the work, and some people think there may be problems with it," she told FoxNews.com.

Sinan Akciz, the other UCI researcher on the study, remained focused on the conclusions.

“What we know is for the last 700 years, earthquakes on the southern San Andreas fault have been much more frequent than everyone thought,” said Akciz. “Data presented here contradict previously published reports.”