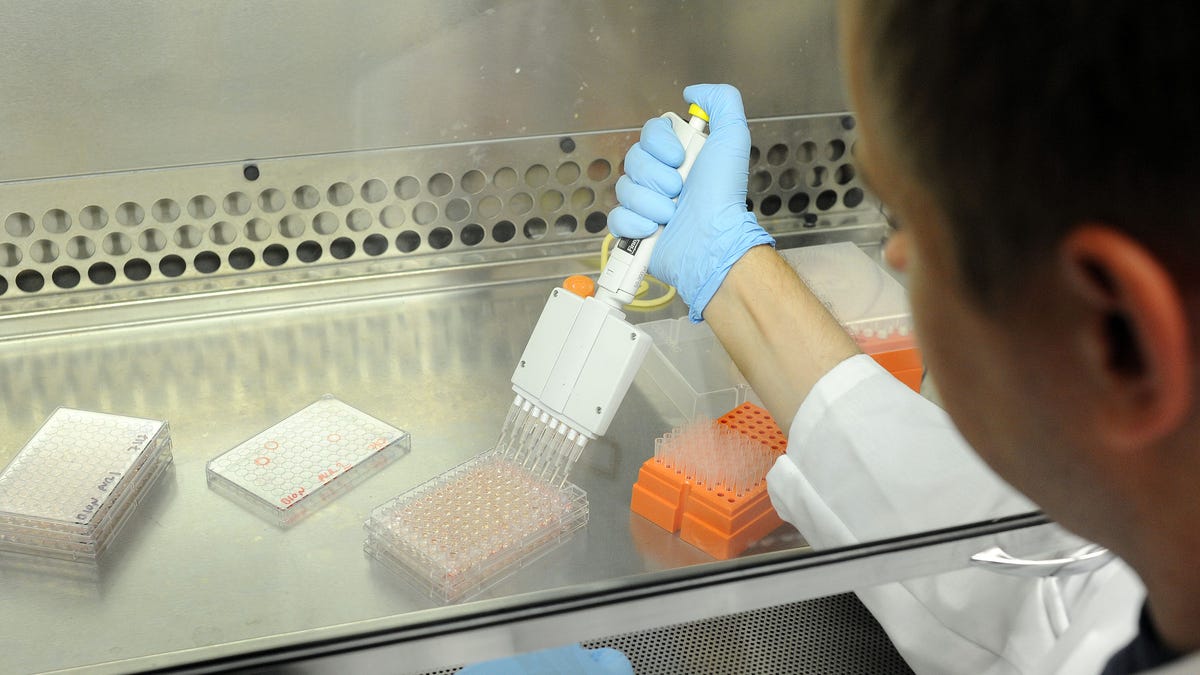

PHILADELPHIA, PA - JULY 31: Scientist Rafal Kaminski, a member of the research team works to introduce cells into lightly infected HIV virus cells as part of the HIV elimination process July 31, 2014 at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Researchers have developed a way to eliminate HIV from cells in the laboratory. There is no time frame for clinical trials. (Photo by William Thomas Cain/Getty Images) (2014 Getty Images)

This week we celebrate National Latino HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. I say celebrate because, in New York, we have much to be proud of.

Over the past decade, New York has reduced its new HIV cases by 40 percent. Furthermore, we are the first state in the nation to commit to ending the AIDS epidemic — an announcement made by Governor Cuomo on the morning of the annual Pride March last June. His plan, “Bending the Curve,” aims to bring the total number of new HIV infections below the number of HIV-related deaths in New York State by 2020.

Perhaps we have failed to provide successful prevention measures in the Hispanic/Latino community because we have failed to understand the diverse cultural identities, norms, and values that exist within the community itself.

Despite our advances, 50,000 Americans still become infected with the virus each year. If nothing were to change, by 2024, that number would increase by a half-million. We have a problem — a problem that only deepens when it comes to Hispanics/Latinos, the largest minority group in the U.S.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Hispanics/Latinos account for 21 percent – one-fifth – of all new HIV cases in the United States. This is a rate three times as high as that of whites. Unpack this statistic a little further: it is expected that 1 in every 36 Hispanic/Latino men and 1 in every 106 Hispanic/Latina women will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime.

We are failing this population. Earlier this month, I attended the 18th Annual United States Conference on AIDS held in San Diego, California. The theme was “Transforming Together,” and the conference opened with a plenary session that put the spotlight on HIV among Latinos, setting the tone for the week.

- Latin America makes its mark in the 2015 Guinness World Records

- Non-Latinos Who Married Latinos: Hollywood’s Famous Mixed Couples

- Paul Rodriguez, skateboarding’s Latino ambassador of cool

- Celebrities Who Said ‘I Do’ In Latin America

- Obama to appear before Hispanic group to address immigration reform delay

- Ted Cruz and other GOP presidential hopefuls look to Romney for help

- Drop In U.S. Poverty Rate Largely Attributable To Improved Economic Outlook For Latinos

- Jeb Bush more focused on business ventures than 2016 presidential bid

We listened to first-hand accounts, discussed the issue with experts in the field, and debated the topic in the larger framework of constantly shifting methods of HIV prevention. Many of these issues are familiar to us at Harlem United, where we run the only Spanish-language AIDS Adult Day Healthcare Center in the state.

While it is generally understood that high rates of infection are linked to socioeconomic factors, such as poverty and/or homelessness, unemployment, migration patterns, language barriers, or lower educational accomplishment, the single most important barrier to HIV prevention in the Hispanic/Latino community is stigma — a mark of shame that persists amidst so much progress.

“The stigma associated with HIV and AIDS is huge,” says Jackie Nieves de la Paz, Managing Director of the HOME program at Harlem United. HOME stands for Helping Our Members Evolve and is the prevention arm for Young Men who have Sex with Men and Young Transgender Females of color.

“It’s cultural. Gender roles, stigma around the disease, stigma around homosexuality — all of these are barriers to prevention, education and treatment in the Latino community,” she adds.

It is not easy to cut through the HIV-equivalent of a “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach in a community that is characterized by rigid machismo/marianismo fears around immigration and a conservative value system.

Taboo and shame are often the only things standing in the way of someone getting tested. (Latinos typically test late, which means they are frequently diagnosed with AIDS within one year of testing positive.)

But maybe we – the health care providers and the community-based organizations – are part of the problem. Perhaps we have failed to provide successful prevention measures in the Hispanic/Latino community because we have failed to understand the diverse cultural identities, norms, and values that exist within the community itself.

The idea that all Latinos speak Spanish, for example, is a common misconception. Nearly 17 percent of Mexicans residing in New York City speak an indigenous language other than Spanish, many only learning the language well after they arrive here. Furthermore, the differences – linguistic and otherwise – between U.S.-born Latinos and foreign-born Latinos are huge. I think it is clear: any solution to reach the Hispanic/Latino population requires an approach as multi-pronged as the community itself.

The question becomes: How do we tailor our services to fill in the gaps? As community-based organizations, we need to take the time to explore non-traditional outreach methods that deliver the message in a way that works. Social networking has proven an important conduit for information on counseling, testing, and referrals to travel peer-to-peer through existing social connections. Social media sites like Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr and Twitter have a similar effect, creating a sense of “virtual” community and camaraderie.

In the case of Harlem United, we use both tactics to spark discussion about the tough stuff, market the importance of early detection, and remind clients they are not alone.

As the Bending the Curve initiative kicks off this week, and as we celebrate National Latino HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, we also need to think big-picture. If we truly aim to end AIDS by 2020, the advancement of a policy, funding, and programmatic agenda that supports the full complexity of the Hispanic/Latino population is imperative. Simply put, it is an essential piece to the puzzle.