(AP1931)

When Republicans gathered in Chicago on June 2, 1880, the frontrunner was a familiar face – former President Ulysses S. Grant, who after serving in the White House from 1869 to 1877 had stayed out of politics for four years. But by seeking an unprecedented third term, Grant had roused strong opposition from two other hopefuls, Maine Sen. James G. Blaine and Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman.

The two men’s supporters helped stop Grant from after installing his personal choice, Sen. Don Cameron of Pennsylvania, as Republican National Chairman.

Grant was counting on Cameron to restore the unit rule where a majority of a state’s delegation could bind all its members, but Blaine and Sherman threatened to remove Cameron if he persisted in trying to lock in the unit rule.

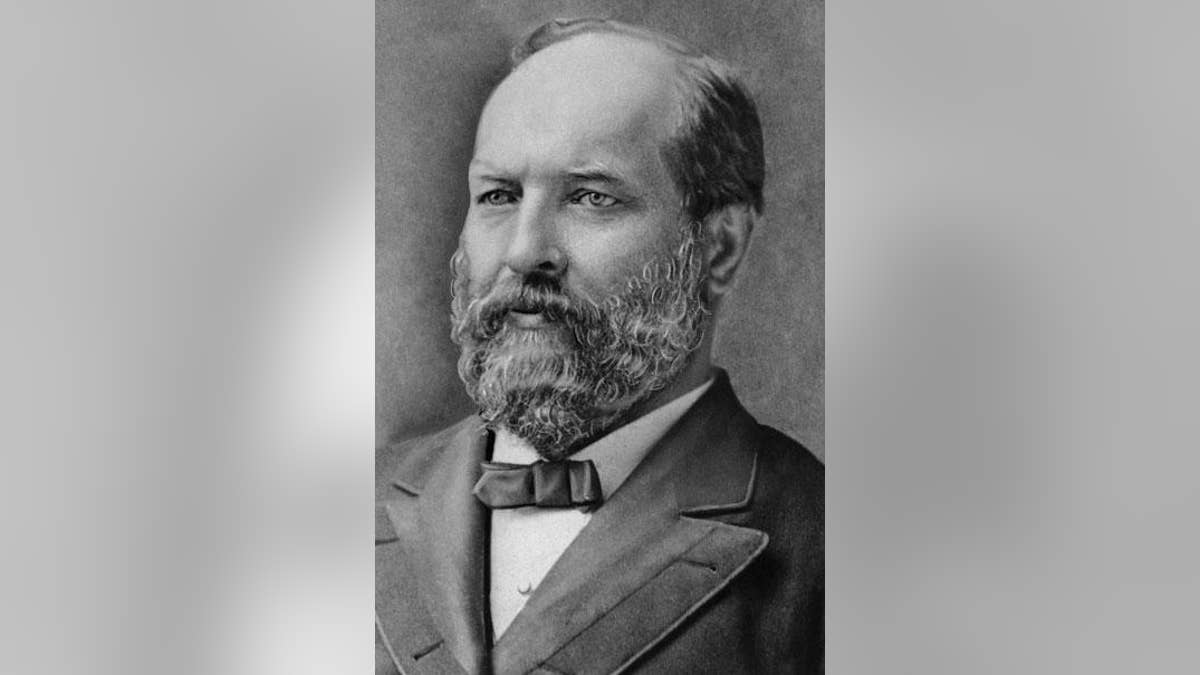

At the convention, Blaine was the first candidate placed in nomination, followed by Grant. Sherman was placed in nomination by Ohio Rep. James A. Garfield, who gave a history of the GOP, discussed party harmony, and described in a general way the kind of man needed in the presidency before finally mentioning the candidate’s name in his final sentence.

Garfield had wanted to be considered himself but knew as long as his state’s deeply respected former U.S. Senator and current Treasury Secretary was a serious contender to lead the party’s ticket. Two more senators and a former ambassador to France were put into the race before the session adjourned.

When balloting began the next morning, Grant led with 304: just 75 short of what was needed for a convention majority. Blaine was close behind with 284, followed by Sherman with 93 and 74 for the other three hopefuls. The convention then proceeded to cast 28 more ballots that day with Grant stuck between 303 and 313 votes before the convention adjourned for the night.

The next morning, Sherman rallied for five ballots but starting on the 34th, Midwesterners began voting for Garfield, who in order to protect his reputation protested that he was not a candidate. The next ballot, both Blaine and Sherman began bleeding delegates to Garfield. By the 36th ballot, it was over as the Ohio congressman took 399 votes and the nomination, followed by the former president at 306 and Blaine at 42.

This made Garfield the GOP’s only presidential candidate whose name was not formally placed in nomination. He went on to win that fall with a substantial margin in the Electoral College – 214 electoral votes to Democratic Winfield Hancock’s 155 – but a popular vote plurality of only 1,998 nationwide.