Political parties haven’t always chosen their presidential candidates through national conventions. Before 1832, caucuses of each party’s members of Congress selected them.

But on September 26, 1831, America’s original “third party” was forced by circumstances to find a different way. Since the Anti-Masonic Party had no members of Congress, local party leaders from twelve states gathered in Baltimore’s Athenaeum and selected William Wirt for president.

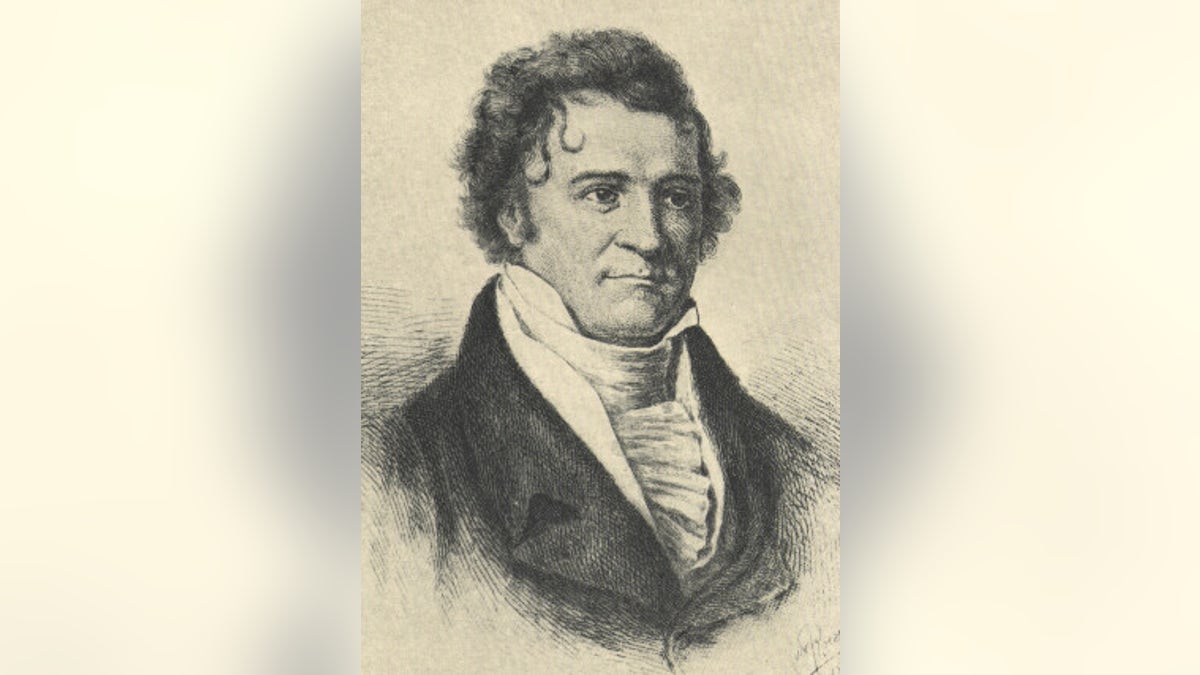

Public domain (William Wirt)

The party had emerged following the disappearance and supposed murder in September 1826 of William Morgan, a disaffected western New York Mason, on the eve of the publication of his book revealing Free Masonry’s secrets.

His body was never found, but Morgan’s disappearance sparked allegations that Masons were a powerful secret conspiracy bent on subverting the country’s republican government. Springing into existence rapidly, the Anti-Masonic Party sought to remove all Masons from public office.

On September 26, 1831, America’s original “third party” was forced by circumstances to find a different way. Since the Anti-Masonic Party had no members of Congress, local party leaders from twelve states gathered in Baltimore’s Athenaeum and selected William Wirt for president.

This populist, anti-establishment movement was limited in influence to the Northeast but won the Vermont governor’s office and legislature. It also had a supporter in the Pennsylvania governor, and emerged in New York as the principal opposition to the Democratic Party of President Andrew Jackson, a prominent long-time Mason.

The Anti-Masonic candidate for president was a respected lawyer whom Jefferson had picked as Aaron Burr’s prosecutor in 1804. Wirt was also the longest-serving Attorney General in history, having labored for twelve years under Presidents James Monroe and John Q. Adams. Upon leaving office, he represented the Cherokees in court battles opposing Jackson’s forced relocation of the tribe to what is now Oklahoma. Ironically, Wirt had been active in Masonry for a few years. He received nearly 8 percent of the vote in 1832 and carried Vermont.

Within a few years, the party was co-opted by Henry Clay’s Whigs. Anti-Masons and Whigs shared many common views, including support for protective tariffs and federal support of internal improvements and, most important of all, opposition to Jackson whom the Anti-Masons saw as a leader of a dangerous scheme to destroy the freedoms of ordinary Americans.

Some Anti-Masons went on to become active in the Whigs and then Republicans, including William Seward, Thurlow Weed and Millard Fillmore of New York and Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania.