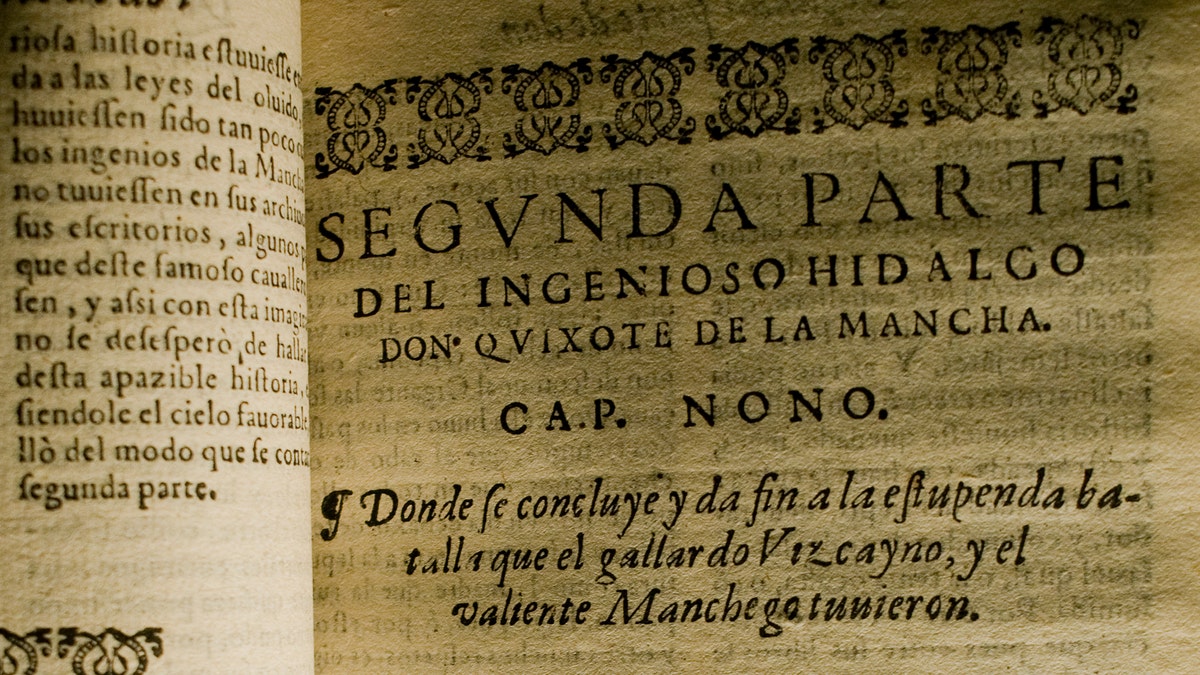

Second edition of Don Quixote, printed in Lisbon in 1615. (Getty Images)

Why is it that from one original language text, nine individual translators come up with nine different translations? Can they be trusted? Are they presenting true versions of the one-and-only, genuine original?

As the Latin saying goes, De gustibus non est disputandum, there is no accounting for tastes, to which I give a tiny twist to say that there is no accounting for translations.

Cervantes did not begin his novel with obscure words, convoluted syntax or complex phraseology, and yet translators manage to complicate, to entangle the start of Don Quixote’s adventures twisting the original to a point that, at times, appears as a pale shadow of the original.

If you pick a copy of El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha written by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra in 1605, you will be reading the original version. If you prefer to read a translation into English, you might fall prey to the whims of translators who will offer “their” personal versions, their interpretation of the Quixote.

Let me roll up my shirtsleeves and instead of telling you about translations, allow me to show you because, after all, the taste is in the pudding, is it not?

Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote’s famous beginning words go like this in the original Spanish:

En un lugar de La Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo que vivía un hidalgo…

Twenty simple words that, seemingly, would offer no problem to a translator. Twenty words of common use, with a simple word order. Possibly the “no ha mucho” could be replaced by the modern “no hace mucho”… the rest is not convoluted or intricate; the syntax is understandable, the meaning plain. However, nine different translators give us nine unlike translations of those 20 words; 18 really because we must deduct La Mancha, which has no translation.

Now read the different versions and judge for yourself:

Thomas Shelton “There lived not long ago since, in a certain village of La Mancha, the name whereof I purposely omit, a gentleman…

Charles Jarvis: “In a village of La Mancha, in Spain, there once lived one of those gentlemen…”

John Ormsby: “In a village of La Mancha, the name of which I have no desire to call to mind, there lived not long ago since one of those gentlemen…”

Samuel Putnam: “In a village of La Mancha the name of which I have no desire to recall, there lived not so long ago one of those gentlemen…”

Clifford H. Galloway: “In one of the villages that dot the Spanish plain of La Mancha –I have no desire to recall its name- there lived not long ago an hidalgo…”

Richard Emery Roberts: “At a certain village in La Mancha, there lived not long ago an hidalgo of the familiar type…”

Walter Starkie: “At a village of La Mancha, whose name I do not wish to remember, there lived a little while ago one of those gentlemen…”

Gerald J. Davis: “Not long ago, in a village of La Mancha, the name whereof I purposely omit, there lived a country gentleman…”

Edith Grossman: “Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago…”

Cervantes did not begin his novel with obscure words, convoluted syntax or complex phraseology, and yet translators manage to complicate, to entangle the start of Don Quixote’s adventures twisting the original to a point that, at times, appears as a pale shadow of the original.

We can assume that the rest of the novel, which at times will pose true challenges of interpretation, even in Spanish, will follow the course that the nine translators have set for themselves. Where there are reeds, there is water, of course, and we must assume that all of them grappled and fought tooth and nail with 17th century Spanish, trying to be original themselves, changing words, adding words, preserving words –hidalgo- distorting the word order –syntax– and trying desperately to present to the English reader a universal work of fiction dressed in Anglo-Saxon garb.

The essence of the 18 words is there. The gist is preserved in the nine versions of En un lugar de La Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo en que vivía un hidalgo… and yet the English in all those versions has something lacking, something that does not ring true, making it sound like a faux Quixote.

Alas, we are all at the mercy of translators and must approach great works of literature in second-hand versions. There is no other way. Or is there?