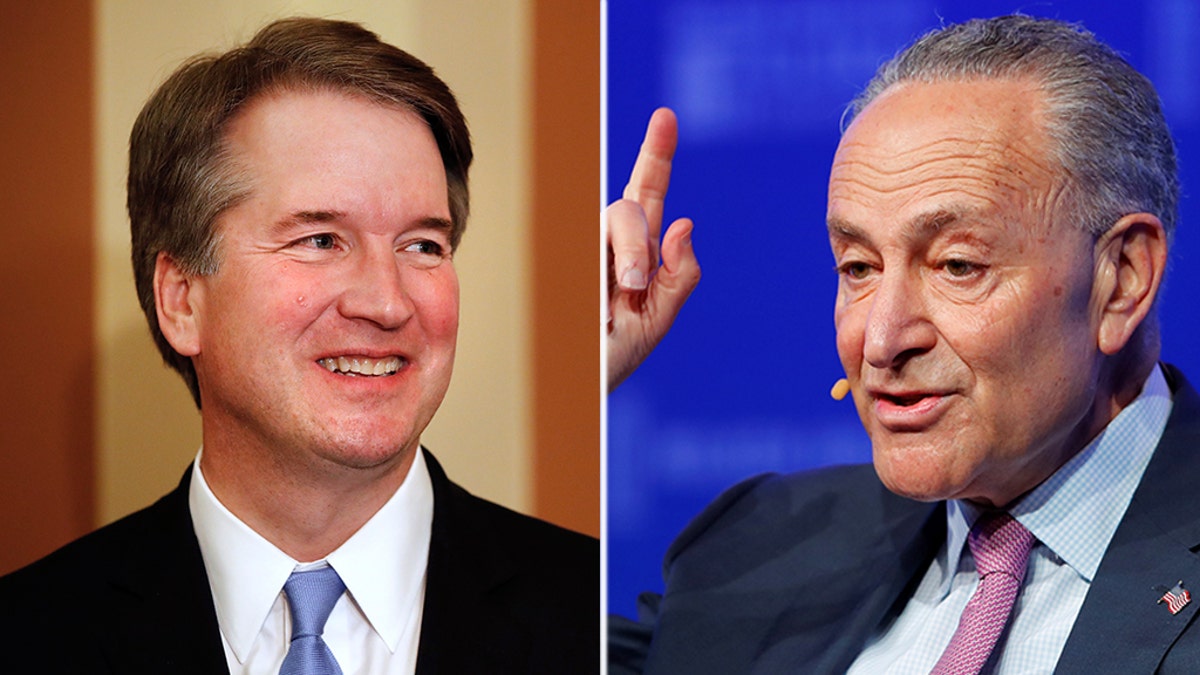

In their efforts to stymie the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, Senate Democrats are now claiming that he will destroy affordable health care.

This attack on Kavanaugh is nonsense – like so many other attacks leveled by Democrats against the judge, who sits on the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District Columbia.

"We Democrats believe the number one issue in America is health care and the ability for people to get good health care at prices they can afford,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said recently. “The nomination of Mr. Kavanaugh will put a dagger through the heart of that cherished belief that most Americans have."

Democrats’ exaggerated attacks on Kavanaugh may provide good political theater – for a while. The attacks might even help the increasingly fractured Democratic minority in the Senate hold together a bit longer.

And the attacks could provide some cover for vulnerable Democratic senators up for re-election in November – including several who represent states that voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

But as a reason for objecting to Kavanaugh’s appointment, the claim that the judge would destroy affordable health care is not supported by records from his many years of government service.

The simple truth is that Schumer has no idea how a Justice Kavanaugh would vote if another legal challenge to ObamaCare reached the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court has decided two such challenges already – a constitutional case in 2012, and a statutory case in 2015. In both cases, the high court rejected the challenges to ObamaCare.

Chief Justice John Roberts, an alleged conservative appointed by President George W. Bush, voted in both cases with the four liberal justices to uphold ObamaCare. Justice Anthony Kennedy – whose retirement created an opening that Kavanaugh would fill if confirmed by the Senate – voted to strike ObamaCare down.

There is every possibility that a Justice Kavanaugh would vote with Chief Justice Roberts in a future ObamaCare case. Kavanaugh might agree with Roberts’ conclusion that ObamaCare’s penalty for failing to buy health insurance was actually a tax, and thus within the limited constitutional powers of the federal government. Or Kavanagh could simply refuse to re-examine the ObamaCare precedent and treat it as settled law.

It is not the business of Supreme Court justices to decide whether ObamaCare is good or bad policy. It’s for elected members of Congress – like Schumer – to debate and decide what kind of national health care policy we ought to have.

We don’t know, because as a judge on the federal court of appeals in Washington, Kavanaugh has not authored any significant opinions on the reach of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause or the spending and taxing powers under which the Obama administration justified its effort to nationalize health care.

But Democrats truly run off the road in thinking that Kavanaugh’s vote would matter. Even if Kavanaugh were to hold the same views on ObamaCare as Justice Kennedy, neither could lift the court’s blessing of the law.

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan voted solidly to uphold ObamaCare; they generally vote against any judicial efforts to limit the federal government’s power over the economy and society.

Justices Antonin Scalia, Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito agreed, however, that Washington could not use its powers over interstate commerce to force unwilling Americans to purchase health insurance and could not use its control over federal spending to coerce states to cooperate with ObamaCare mandates.

But Chief Justice Roberts, in a decision that many conservative legal scholars criticized heavily at the time, joined the four liberals in concluding that the Constitution allows the federal government to use its taxing power to punish those who would not buy health insurance.

Thus did Roberts save ObamaCare. Kavanaugh’s replacement of Kennedy cannot change that outcome. And of course, we can only guess how Trump-appointed Justice Neil Gorsuch (or, for that matter, any of the conservative justices), would vote.

Furthermore, in the one case where Kavanaugh himself encountered the constitutionality of ObamaCare, he did not welcome conservative arguments. In 2011 – before the Supreme Court heard the first challenge to ObamaCare – Kavanaugh concluded that plaintiffs could not challenge the law because they were attempting to attack a tax before it was collected.

Under the Anti-Tax Injunction Act, Kavanaugh argued, the plaintiffs first had to pay the ObamaCare tax penalty and then ask for a refund – only then could they raise constitutional problems with the law.

In a nutshell, Kavanaugh took the view that the penalty for refusing to buy health insurance was a “tax” – basically the same position that Roberts would take in siding with the Obama administration, though he and the four liberals brushed aside Kavanaugh’s claim that the case was premature.

Kavanaugh indeed anticipated Roberts. After concluding that the lawsuit was barred by the Anti-Injunction Act, Kavanaugh went on to add (gratuitously, perhaps) that Congress might later go on to reconfigure ObamaCare and make the individual mandate a (constitutional) tax. If Congress did that, Kavanaugh opined, the mandate would fit “comfortably” under Congress’ taxing power.

That is the part of Kavanaugh’s opinion at which some of his conservative critics balk. Their charge is that he provided a “roadmap” for the Obama Justice Department to defend the health care law, and for Roberts to uphold it. As Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, has noted, Kavanaugh “frankly was criticized by conservatives for not going far enough.”

A careful reading of Kavanaugh’s opinion shows that he would likely have come out on the same side as Chief Justice Roberts – and President Obama and Sen. Schumer, for that matter. Schumer is not just mistaken in making his predictions, but he has read Kavanaugh’s opinion exactly opposite to its actual meaning.

If Schumer can correctly read Kavanaugh’s opinion, then he must believe that Kavanaugh opposes the policy of national health care, rather than its constitutionality. But it is not the business of Supreme Court justices to decide whether ObamaCare is good or bad policy.

However, by saying that a Justice Kavanaugh would “put a dagger through the heart” of affordable health care, that is exactly what Schumer is implying. It’s for elected members of Congress – like Schumer – to debate and decide what kind of national health care policy we ought to have. The task of the Supreme Court thereafter is two-fold: to interpret what Congress has done, and to measure it against the yardstick of the Constitution.

Ironically, Democrats are accusing Kavanaugh of blurring the lines between policy and law – the very fault that Kavanaugh’s nomination will begin to correct.

Robert J. Delahunty is a law professor at St. Thomas University.