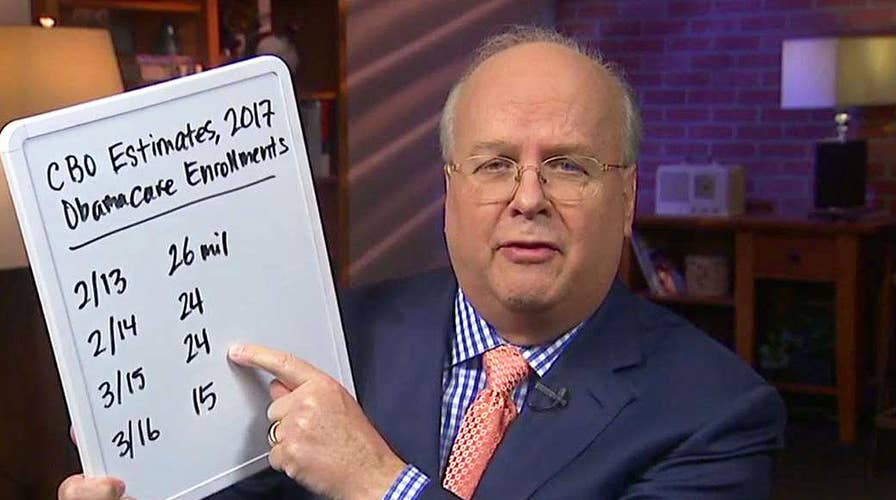

Karl Rove fact checks CBO report on health care bill

Fox News contributor provides insight on 'The Story with Martha MacCallum'

Republicans have tasked themselves with fixing ObamaCare—repealing and replacing it with something better, that lowers premiums and offers greater choice, without pulling the rug out from under the millions of Americans who have gained coverage under the law.

Reading Wednesday’s Congressional Budget Office score of the American Health Care Act, you’d think this was Mission Impossible, and that states would “race to the bottom” in pursuing waivers that would give them more flexibility in how insurance is priced and regulated. CBO projects, for instance, that costs for older or sicker patients could rise sharply for patients living in states that pursued the most aggressive waivers.

The CBO’s job is to score legislation as written—and they’ve certainly pointed out some shortcomings in how the AHCA is currently structured. But CBO has also highlighted key improvements Republicans in the Senate could make to stabilize markets: increasing reinsurance funding for high-cost patients, offering means-tested cost sharing subsidies for the low-income uninsured, and strengthening incentives for young, healthy populations to get and hold coverage.

The Dept. of Health and Human Services could be tasked with studying, in real time, the effects of state waivers on important measures like access to care, health outcomes, and out of pocket costs.

Taken together, these three fixes would enable states to experiment with more affordable plan designs while still providing robust coverage to patients with expensive pre-existing conditions.

The Republicans are on the right track in one critical respect, noted in the latest CBO score. Although the coverage score still gives many pause (23 million more uninsured compared to the ACA by 2026), CBO projects that both the AHCA's Patient and State Stability Fund and the Federal Invisible Risk Sharing Program would help to put downward pressure on premiums.

Well-designed and well-funded risk pools or reinsurance would certainly go a long way in stabilizing state insurance markets. By offsetting claims associated with high cost patients, these programs can lower premiums across the board, keeping them affordable for the vast majority of healthy enrollees. The AHCA’s programs simply need more funding (some estimates have suggested $15-20 billion annually.)

The next step is to offer cost sharing subsidies for lower income enrollees, in addition to the AHCA’s flat tax credit. Adding means-tested cost-sharing subsidies will help keep coverage within reach for the populations who need it most. As long as cost sharing subsidies are available for these populations, higher deductible or catastrophic plans could offer lower premiums for healthier enrollees who just need protection against major medical events.

Finally, the Senate needs to address the AHCA’s penalty for going without coverage. CBO expects that, as currently structured, the law would encourage younger, healthier enrollees to stay uninsured because the penalty for going without coverage is too weak. In this respect, it suffers from the same problem as ObamaCare, which hasn’t attracted enough young, healthy enrollees.

The truth is, no one really knows a single, blanket solution for this problem. The best approach is to allow the states to come up with their own coverage strategies. Some might choose auto-enrollment in a zero-deductible catastrophic plan, larger or longer penalties for buying coverage after you become sick, or other approaches. Over time, we could learn what works best.

The Senate can also reassure skeptics of state flexibility by explicitly including guardrails that help protect patients, and ensure that states focus on meeting clear goals for vulnerable populations.

The Department of Health and Human Services, for instance, could be tasked with studying, in real time, the effects of state waivers on important measures like access to care, health outcomes, and out of pocket costs. HHS could also help states model and evaluate waiver proposals, collect data, and ensure greater transparency around health plan costs and quality.

Congress should also tie reinsurance funding to states reforming their health care markets to promote competition and transparency—helping patients and consumers to find providers who deliver better care at lower cost.

ObamaCare’s one-size-fits-all plan design has driven up costs, and locked healthier patients out of the market. States should be encouraged to make greater use of health savings accounts, allow insurers to design different cost sharing or provider networks within established categories of essential health benefits that provide comparable access to care at lower cost, and offer more value-based insurance designs that waive co-pays or deductibles for high value services.

House Speaker Paul Ryan, speaking at an Axios event recently, said, “Let's just pay for the people who are catastrophically ill. Let's just do that. Because I don't think anybody, Republican, Democrat, whatever, thinks that if a person gets breast cancer in her 40s, she should go bankrupt for getting it."

He’s right. Doing so will not only allow Republicans to answer serious critics of the AHCA, but empower states to find ways to supercharge health care competition that improves health outcomes at less cost to patients and taxpayers.

The CBO score isn’t cause for abandoning waivers. It’s a call to get serious about making them work.