Fox News Flash top headlines for June 8

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

Many patient advocacy groups representing the 6 million Americans suffering from Alzheimer’s disease are hailing the FDA’s approval of a new treatment for Alzheimer’s, aducanamab – the first since 2003. Some in the medical community have opposed the decision, arguing that the therapeutic benefit has not been established. Nevertheless, doctors may now prescribe the drug, and additional research will be needed to confirm its efficacy at slowing cognitive decline, which it appears to do, at least modestly, for some patients.

Having cared for hundreds of Alzheimer’s patients over my 40-year career and been intimately involved as a researcher since the earliest days of investigation into this disease, I understand the concerns. But I’ve firmly landed on the side of hope and excitement for what this milestone promises for the future.

Today, there are approximately 120 clinical trials underway, several of which may prove critical in combating the disease— more than half tackling a variety of aging-related pathways. This makes me very optimistic about the potential for future breakthroughs.

Alzheimer’s research has progressed dramatically in the last decade. Before then, researchers faced two challenges that set Alzheimer's apart from, say, cancer or heart disease. First, animal models were not useful, since animals in the lab don't possess exclusively human ("executive function") brain capabilities that are diminished and lost as Alzheimer’s progresses.

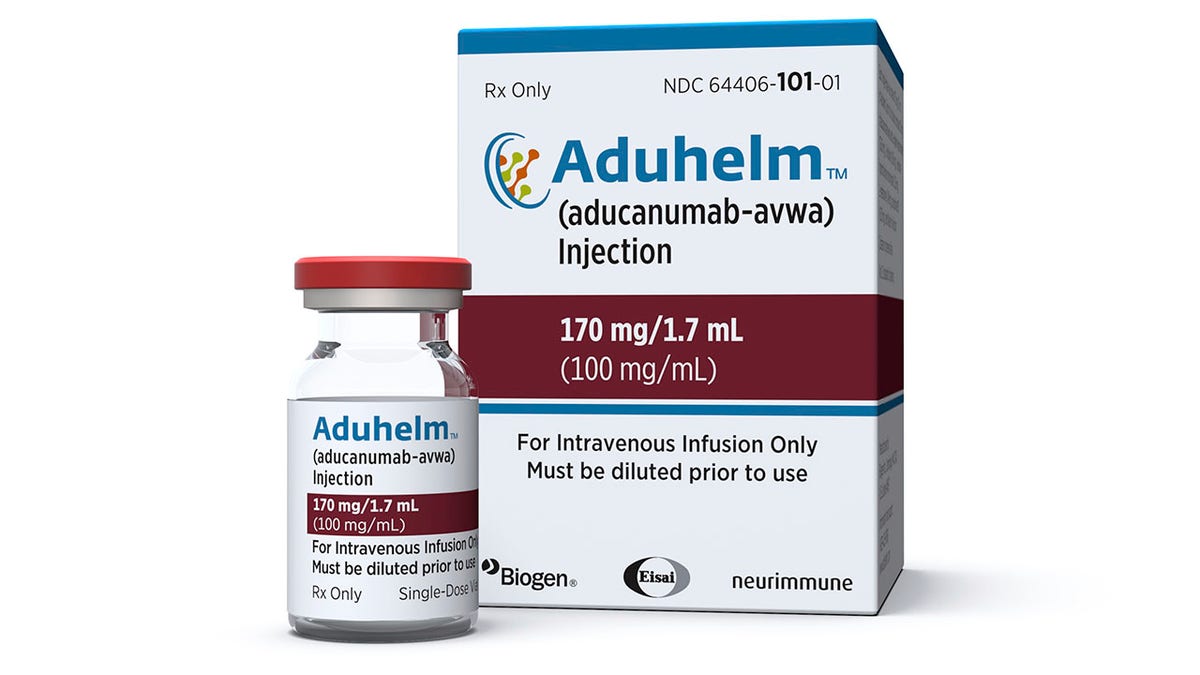

This image provided by Biogen on Monday, June 7, 2021 shows a vial and packaging for the drug Aduhelm. On Monday, June 7, 2021, the Food and Drug Administration approved Aduhelm, the first new medication for Alzheimer’s disease in nearly 20 years, disregarding warnings from independent advisers that the much-debated treatment hasn’t been shown to help slow the brain-destroying disease. (Biogen via AP)

Second, until recently, we had no way to definitively diagnose Alzheimer's in living human patients. While there are many underlying causes and various forms of dementia, the hallmarks of Alzheimer's—the accumulation of beta amyloid plaques and tau proteins in the brain—could be detected only through autopsy.

For years, we could only test drugs in patients who were presumed to have Alzheimer's. We now believe that approximately 30 percent of patients in Alzheimer's trials just a decade ago did not even have the disease. This means the data in those earlier clinical trials were flawed and inadequate to prove a drug's effectiveness.

All that changed in 2012 with the FDA’s approval of the Amyvidä PET scan, which could identify amyloid plaques in the living brain—empowering researchers for the first time to ensure that clinical trials included only those patients who in fact had amyloid plaques. This breakthrough is what made the trials for aducanumab, which specifically targets amyloid, revolutionary.

In this 2019 photo provided by Biogen, a researcher works on the development of the medication aducanumab in Cambridge, Mass. On Monday, June 7, 2021, the Food and Drug Administration approved aducanumab, the first new drug for Alzheimer’s disease in nearly 20 years, disregarding warnings from independent advisers that the much-debated treatment hasn’t been shown to help slow the brain-destroying disease. (Biogen via AP)

Since 2012, more diagnostic tests have been authorized, including PrecivityADä, a blood test that makes testing for Alzheimer's more widely accessible and affordable. (Disclosure: The Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation was an early funder of Amyvidä and PrecivityADä research.) Other promising blood tests are also on the way.

FDA APPROVAL OF BIOGEN'S ALZHEIMER'S DRUG LEAVES SOME ‘DISAPPOINTED’

This means that patients with memory problems can now go to the doctor for a blood test to determine if they have Alzheimer’s disease and receive a definitive diagnosis for care and life planning, and determine eligibility for clinical trials.

More from Opinion

Perhaps most exciting is that new tests are helping researchers evaluate an array of factors that may contribute to the disease. Because aging is the most important risk factor, research today is addressing a broad range of characteristics of the Alzheimer's brain, including inflammation, metabolic disturbances, vascular problems and genetic mutations.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Drugs currently in development are focusing on these targets and others, which will open the door to new precision combination therapies, similar to those used to treat many cancers today.

I expect that soon clinicians will have a range of medications from which to customize treatments, and patients will benefit from a combination of drugs—maybe one to address amyloid buildup, another to address tau problems, plus an anti-neuroinflammatory drug, and one that helps signals cross the brain’s synapses. New therapies will slow the progression and allow patients to better retain their cognitive function and quality of life.

Howard Fillit, M.D., is founding executive director and Chief Science Officer of the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation. He is a clinical professor of Geriatric Medicine, Palliative Care & Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. (Mt. Sinai)

Today, there are approximately 120 clinical trials underway, several of which may prove critical in combating the disease— more than half tackling a variety of aging-related pathways. This makes me very optimistic about the potential for future breakthroughs.

I am excited to see broader consensus in the research community for the need to take fresh looks at what we are now learning about the biology of aging.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

I am also hopeful about a future that offers effective preventative measures—including medications and lifestyle changes—so that those who are at risk for developing the disease can prevent or delay its onset.

It only gets better from here for patients and their families afflicted by this disease.