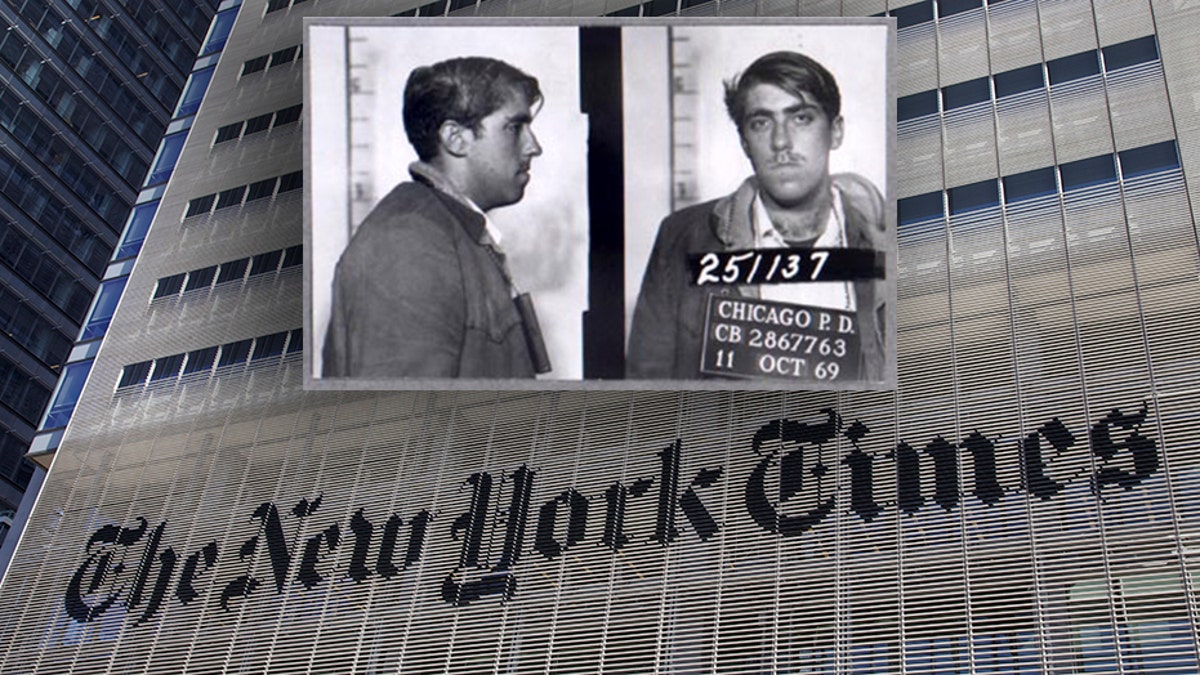

The New York Times fails to mention the criminal past of op-ed contributor Mark Rudd. (MoMorad)

The New York Times published an op-ed by Mark Rudd about the role of black students during the infamous Columbia protests of 1968 on Sunday -- without mentioning that the column’s author was a widely controversial far-left, anti-American activist known for his ties to the deadly Weather Underground.

The piece headlined, “The Missing History of the Columbia ’68 Protests,” describes Rudd as a leader of the campus protests at Columbia University and the president of the Columbia branch of Students for a Democratic Society. Rudd was also a key member of the militant Weatherman faction – but Times readers wouldn’t know that detail of his life.

Rudd and the Weathermen were a divisive group that once essentially declared war on the United States. They went by the name Weather Underground once they came under fire for blowing up a New York City townhouse.

The New York Times did not respond when asked why it didn’t disclose Rudd’s controversial past.

“The Times clearly didn't do enough in identifying Rudd for this op-ed. He is, indeed, an educator and community organizer, but he's probably more famously known for his Weather Underground activities,” media analyst Jeffrey McCall told Fox News.

McCall, a respected DePauw University professor, feels that leaving out such an important detail was “unwise” and misleading to the audience.

“I doubt it was an accidental omission,” McCall said. "I believe a news organization should always give the audience full context on sources and opinion writers."

Rudd’s column attempts to fill in the gaps of the narrative surrounding the ’68 protests against Columbia University’s role in the Vietnam War and its plans to expand its campus. Rudd wrote that popular memory considers the protests a “high point” in the campus anti-war movement and “a mile marker in its radicalization,” but claims the storyline is incomplete.

“It misrepresents what made the protests so powerful -- the leadership of the black students,” Rudd wrote. He explains that he arrived on campus in 1965 and started hanging out with “a group of campus radicals” who felt the war was unjust, illegal and a “war of choice.” He also says his group combatted racism that plagued the university.

“We had grown up in the wake of World War II and watched the civil rights movement take shape in the South, and the university’s support for the war and its institutional racism shook us to our core,” Rudd wrote.

By 1968 Rudd’s group had teamed up with Student Afro-American Society, which he says was comprised of “the more politicized of the few black students” at Columbia. They eventually occupied the campus’ main building and held the dean of the college hostage.

“There was a difference between us, though. We white kids were ragtag, messy, arguing constantly with each other,” Rudd wrote. “But the black students, inspired by the civil rights movement in the South and by their own parents’ lifelong struggles, were certain that they had to barricade the building as their own disciplined statement.”

Throughout the Times column, Rudd went on to praise the black students for amplifying the protests that eventually resulted in the school shutting down for the remainder of the semester.

“Because of their stand, hundreds and then thousands of students and local residents rallied to the cause, and within two days three more buildings were occupied,” he wrote.

Rudd’s piece was praised on social media for finally giving the black students a place in the history book when it comes to the uprising of 1968, but it’s unclear if people praising Rudd are aware of his shady past.

The Times refers to Rudd as an “educator and community organizer,” but the late political activist Tom Hayden once used drastically different rhetoric to describe him.

“This is the same Mark Rudd I met in the heat of the 1968 Columbia University student strike, the Mark Rudd who ended a letter to Grayson Kirk, Columbia’s president, by declaring, ‘Up against the wall, mother-----r!’, the Mark Rudd who proudly led Students for a Democratic Society to close its offices and end its organizing efforts in the midst of the greatest student rebellion of the 20th century, the same Mark Rudd who went underground and supported a plan to bomb Fort Dix, which went awry and killed three of his friends — all by the time he was 22 years old,” Hayden wrote.

Rudd went into hiding in 1970 when the Weathermen exploded a bomb in the basement of a New York City home, killing three members of the group and destroying a four-story townhouse. Rudd wrote years later that his intention was to detonate the bomb at dance of non-commissioned American officers and their dates to “bring the war home.”

“I escaped an FBI entrapment on 23rd St. in Manhattan by running down into the subway and up again onto the street and hopping onto a bus,” Rudd once wrote before bragging that he had planned ahead and always carried spare change for the bus.

Rudd was in hiding for over seven years and only turned himself in after federal charges related to the bombing and conspiracy were dropped amid disclosures of the Watergate scandal.

Weather Underground was also responsible for a variety of anti-American actions, including bombing the Pentagon in 1972 and other violent, sometimes deadly, acts.

These days, Rudd brags about his controversial past on his website and documented his time with the Weathermen in a 2009 memoir.

Lucky for Rudd, the Times helps glorify his past by allowing him to write opinion pieces without disclosing the skeletons in his closet.