Hector Barajas served in the legendary 82nd Airborne, but was never a citizen. Now, he says, he's been banished.

TIJUANA, Mexico – They served the United States on battlefields from Korea to Iraq, but now they live in the shadow of the nation they once served, deported to Mexico for offenses as minor as getting caught with marijuana.

While many U.S. veterans find adjusting to civilian life difficult, writing a bad check, possessing marijuana or getting into a bar fight are enough to get some veterans banished from the nation they fought to protect. That’s because they were not citizens when they donned the uniform and took up arms for America. Any U.S. obligation to them ended when they got in trouble with the law.

“Some people get out of the military and go back to communities with good support systems and some don’t,” said Hector Barajas, 38, one of several veterans who lives in the Deported Veterans Support House, a modest building in the Otay Centenario neighborhood on the east side of Tijuana. “Many of the men being deported served in Vietnam and didn’t get the treatment that we’re supposed to get.”

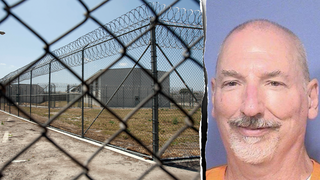

Reminders of their service and evidence of their patriotism adorn the walls of the home known as “The Bunker.” Draped in flags, decorated with military memorabilia and photos, the 1,000-square-foot, three-room building is a step up from the cramped apartment Barajas used to share with fellow “banished veterans.” At any given time, there are half a dozen or more men living in the home, just 3 miles from the San Ysidro border crossing.

“I knew the risk and I know I’m paying for it. I just hope I don’t have to pay for it forever.”

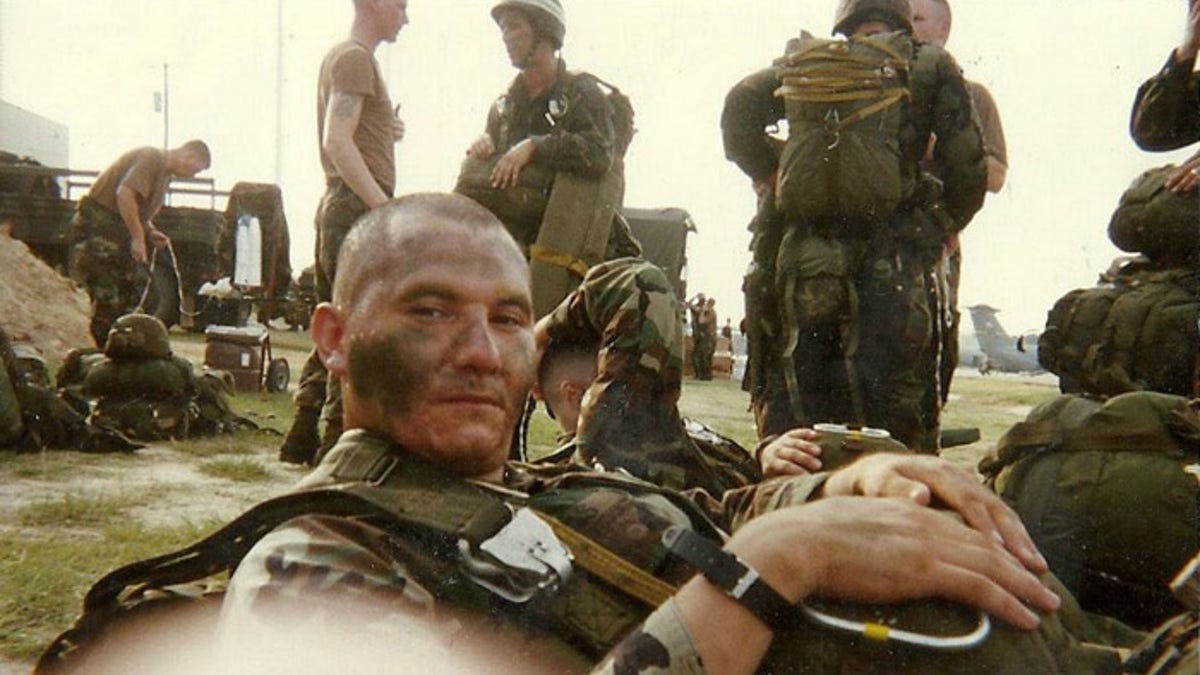

Although Barajas has become the patron saint of deported veterans, his journey to The Bunker is not unique. He moved to the U.S. as a 7-year-old, and became a legal resident through his parents. When he was old enough, he joined the U.S. Army, landing in the fabled 82nd Airborne Division where he served from 1995 to 2001.

Part halfway house, part nonprofit nerve center, "The Bunker" is Barajas' home. (FoxNews.com)

Not long after he was honorably discharged, Barajas was arrested after an incident in which a firearm was discharged from his vehicle. No one was hurt, but he pleaded guilty and did two years in prison. He was deported for the first time in 2004, and again in 2009. He left his wife and young daughter behind in California.

In Mexico, Barajas battled drug addiction for years before getting himself clean in 2013. By then, he also had found an underground community of similarly situated veterans who had come back from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq only to be sent across the border. He opened his apartment to as many as he could, and nearly two years ago, Barajas and his band of brothers moved into their current digs.

Veterans who were deported despite serving in the military have found a home in Tijuana, but they hope it's not permanent. (FoxNews.com)

Structure, chores and self-reliance help the veterans tap the discipline they once knew in the military, and aid Barajas in keeping order. When one lodger moves on, another is always there to take his or her place.

For Barajas, it is more than just a halfway house. From The Bunker and through the nonprofit deportedveteranssupporthouse.org, he tries to help U.S. vets who show up at his door or find themselves sent to as many as 22 different nations, including Bosnia, Ghana and Ecuador. Much of his time is taken up by long-distance counseling and political advocacy.

“We support deported veterans on their path to self-sufficiency by providing assistance in the realms of food, clothing, and shelter as they adjust to life in their new country of residence,” reads the organization’s mission statement. “Ultimately, we hope to see an end to the need of our services as we advocate for political legislation which would prohibit the deportation of United States service personnel, both former and current. We advocate for veterans and their families.”

According to Barajas, the soldiers and sailors he helps face endless problems -- from the possible loss of native citizenship to the possibility of criminal charges awaiting them in their original country for their service in the war.

No federal agency tracks the number of deported U.S. veterans, but some immigration advocates estimate there are hundreds, if not thousands. Barajas says he is aware of more than 300 spread throughout the world and typically sent home to their birth countries even though they often have no family or connections there.

Patriotism still runs deep at "The Bunker," where deported veterans help each other survvive. (FoxNews.com)

Most deported veterans were permanent residents, or green-card holders, at the time they enlisted, according to Department of Defense spokesperson Lt. Cmdr. Nate Christensen. He said about 5,000 documented noncitizens sign up for the military every year.

The military does not require citizenship, just status as a lawful permanent resident. The Pentagon estimates that up to 65,000 noncitizens are now serving in the U.S military. A prominent incentive for joining is that the resident will be fast-tracked to naturalized citizenship. But a brush with the law before the paperwork is complete means expulsion.

In one particularly cruel irony, honorably discharged veterans like Barajas remain eligible for VA benefits and medical treatment for injuries suffered during their service. But most of these benefits lie in the U.S., beyond their reach.

“I’m still entitled to a military funeral and the VA will pay for the marker,” he said. “I can’t come back now, but I can be buried in Arlington. Only then will they give me an American flag and say, ‘Thank you for your service.’”

At the heart of the issue lies the question of whether non-citizen veterans earned special treatment on the battlefield. Former Marine Dominic Certo, author of “Gold in the Coffins,” and an adviser to the veterans advocacy organization Operation Homefront, believes they do.

“Anyone who has served our country and risked their lives or provided service for the citizens of this country as a veteran deserves amnesty -- especially when there are so many who have done nothing to earn citizenship or provide a military service to our country,” Certo said.

William Gheen, president of the Americans for Legal Immigration, disagrees.

“Americans want both legal and illegal immigrants that commit crimes to be deported in the interest of protecting American property, jobs, taxpayer resources and lives,” said Gheen. “Immigration laws should be enforced equally.”

Often, noncitizen veterans are deported without even getting to tell their side of the story, said Margaret Stock, an Alaska-based attorney, retired Army lieutenant colonel and West Point professor. Stock has taken on several veterans’ deportation cases, and says the situation has become significantly worse under the Obama administration.

“The administration is deporting as many criminal aliens as possible for the numbers, but it doesn’t take into account military service,” Stock said. “Most people also don’t understand how complicated immigration law really is and how easy it is to run afoul of these complex laws.

Making matters worse, Stock said, is that defendants in deportation cases are not automatically given attorneys and often can’t afford to hire their own, resulting in many being wrongfully deported.

Any lawful permanent resident, veteran or not, can be deported upon conviction of a crime that falls under the extremely broad umbrella of a Crime Involving Moral Turpitude. This can be either a misdemeanor or felony, and typically includes anything from assault, fraud and perjury to robbery, theft and bribery. The rulings are often viewed by immigration lawyers as arbitrary and the immigration code now includes scores of petty offenses listed alongside the severe ones, all punishable by deportation.

Still, the federal government is very deliberate in its review of cases involving veterans, insisted Gillian Christensen, spokeswoman for the U.S. immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“Any action taken by ICE that may result in the removal of an alien with military service must be authorized by the senior leadership in a field office, following an evaluation by local counsel,” she said. “ICE specifically identifies service in the U.S. military as a positive factor that should be considered when deciding whether or not prosecutorial discretion should be exercised.”

The final order of removal is issued not by ICE, but a federal immigration judge.

Tijuana’s proximity to the U.S., together with the fact that many deported veterans were originally from Mexico, makes it an all-too-familiar landing spot. At shelters and barrios throughout the city, men of all ages who served in the U.S. military can be found.

Andres de Leon, 72, crossed into the U.S. as a teenager, fought in Vietnam and was honorably discharged from the Army in 1969. Six years later, drugs and joblessness led to a brush with the law. He was deported in 1975, and has lived in Tijuana ever since. His dream of returning to the U.S. still burns.

“My friends are all dead now,” he said from the kitchen of the Tijuana shelter that has affectionately been named “Chow Hall." “But I still want to go back.”

Other cases are more complex. Daniel Torres, 29, came to the U.S. illegally with his family as a child, but enlisted as a Marine in 2007 and was soon deployed to Iraq. Technically, he was not a lawful resident and should never have been accepted.

“I just didn’t want to be another Mexican living in the United States,” Torres said. “I wanted to say I had contributed, that I had done something for the country.

“After Iraq, they needed volunteers for Afghanistan and I liked military life and was considering being a lifer,” he added. “But my legal status was always in the back of my mind.”

Torres lost his wallet during pre-deployment training. When he went to obtain a new one, his secret got out and he was dismissed with a general discharge – largely on the strength of high recommendations from his superiors.

Torres missed the military, and sought to join the French Foreign Legion. But injuries sustained in Iraq disqualified him and, unable to legally return to his family in the U.S., Torres drifted to Tijuana. He works as a paralegal during the day and goes to law school at night.

“It would be easy for me to play the victim, but I don’t feel I should,” he said. “I knew the risk and I know I’m paying for it. I just hope I don’t have to pay for it forever.”