Clock ‘doctors’ help keep old clocks ticking

A group of clock 'doctors' are working to preserve the art of horology in hopes that the next generation can learn about the way humans used to keep time before the digital age

A team of clock “doctors” is working to preserve some of the country’s oldest clocks before time runs out.

Lindsay Rasberry and many people like him fell in love with clocks at an early age. He has several of them scattered throughout his home in Tupelo, Miss. and many of them can be heard chiming at the top of every hour. The oldest piece he has is from the 18th century. The front room of the house has been turned into a workshop where he repairs clocks from across the country.

“It started at such an early age for with me,” Rasberry told Fox News. “[My mom] says that I would be standing next to her in a car seat and she would be driving down the road and she would notice a clock inside a storefront and I would yell clock, clock,” he said.

Rasberry has repaired thousands of clocks over the years. He has also trained at least 10 people in the art of horology and hopes that more people get in involved in the rare practice.

“Horology is the study of time,” Rasberry said. “[Or] anyone who deals with clocks or any facet of time keeping.”

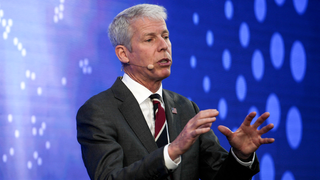

Lindsay Rasberry poses for a photo at his clock repair workshop located inside his home in Tupelo, Miss. Rasberry has trained ten people over the years and hopes more people practice horology. (Fox News)

He noted that he first gained a professional interest in clocks after meeting a man by the name of Ellis Tomsky, an avid clock collector in Tupelo. Rasberry apprenticed with Tomsky for 10 years to learn how to repair clocks. Since many of the manufactures that made the old clocks have since disappeared, a network of horologists and clock enthusiasts like Rasberry work to repair them. Repairs for the timepieces range from under $100 to thousands of dollars.

Rasberry is one of 13,000 people who are members of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors (NAWCC). Many of the members meet regularly to discuss their collections of rare clocks and watches and also to share tips about repair techniques. Donna Kalinkiewicz is a member of an NAWCC group in Birmingham, Ala. and Atlanta. She was also one of Rasberry’s apprentices when he operated a shop in Georgia. She said teaching the next generation how to read analog clocks is important.

“I think everybody should teach a child how to read an analog dial,” Kalinkiewicz said in her clock repair workshop in Birmingham. “You’re always going to have those people who rely on digital [because] that’s all they know [and] that’s all they care about. All they understand is 12:48 [but] they don’t understand that that’s 12 minutes to one,” she said.

Kalinkiewicz explained that phrases such as ‘a quarter past the hour’ or ‘fifteen minutes til’ may be lost forever. She hopes young people take an interest in time keeping since many of the members of NAWCC groups around the country are in their golden years.

Donna Kalinkiewicz works on a clock at her workship inside her home in Birmingham, Ala. Kalinkiewicz says children need to be taught how to read analog clocks instead of just relying on digital devices to tell time. (Fox News)

“Unfortunately, a lot of the people who are doing the work right now are getting very old,” Kalinkiewicz said. “It is an art that may die if we don’t try to preserve it.”

Gary Landis, a member of the Birmingham group, agrees. Landis remembers a time when clocks had to be wound up every day. He is betting that nostalgia catches the eye of young people.

“Everybody has grandma’s clock in the attic and it’s a nostalgia thing and they want to bring it down,” Landis said. “They remember as a little child that grandma had that clock.”

According to Landis, NAWCC often works to get children interested in horology by hosting field trips at its national headquarters in Columbia, Pa. He also said he and other members try to spark interest among their children and grandchildren.

“By ignoring the history of clock making and watch making, you don’t get the full advantage of where we’ve come as far as technology is concerned and so to me they fit together,” Landis said. “We don’t want to lose sight of that.”