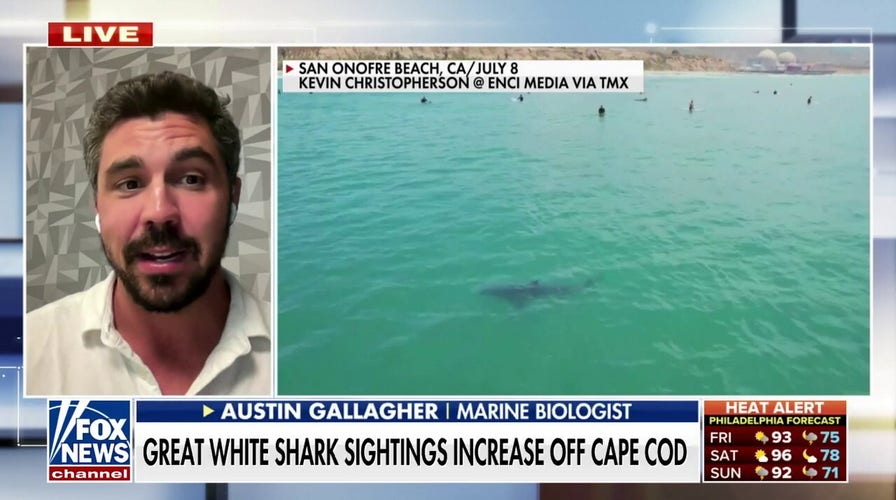

Great white shark sightings increase off Cape Cod

Marine biologist Austin Gallagher says warmer temperatures, advanced technology, and a growing population contribute to the spike in shark sightings in the U.S. on ‘America Reports.’

Approximately 800 great white sharks have visited Cape Cod waters from 2015 to 2018, researchers say.

A population study was published Thursday in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

The team of scientists from the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth's School for Marine Science and Technology and the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries conducted a mark-recapture survey to estimate the size of the newest white shark hotspot.

The conservancy tweeted that it represents the "first estimate of white shark abundance ever produced in the North Atlantic Ocean."

SHARKS MIGHT BE CONSUMING COCAINE AS AMERICA'S DRUG CRISIS SPILLS INTO THE SEA

Research vessel looks for Great White Sharks, off the coast of Chatham, Massachusetts, on Oct. 21, 2022. (JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images)

The number of white sharks was found to peak in the late summer and early fall when water temperatures were the warmest.

Mark-recapture uses repeated surveys of uniquely marked animals to estimate population size – although sharks can also be identified based on unique markings and notches in their dorsal fins.

Dr. Greg Skomal, shark researcher for Massachusetts Marine Fisheries, captures video footage of a great white shark while the crew listens for its radio tag off the coast of Chatham, Massachusetts, on Oct. 21, 2022. (JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images)

From over 2,800 videos compiled during 137 survey trips over the summer and fall of 2015-2018, the scientists identified 393 individual white sharks included in its model.

"By comparing the number of previously identified individuals to new individuals encountered over time, we were able to estimate the number of sharks visiting the site in each month of the survey, as well as the total for the four-year period," Megan Winton, lead author of the study and a staff scientist for the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, explained to The Boston Herald.

An Atlantic White Shark Conservancy research vessel looks for great white sharks off the coast of Chatham, Massachusetts, on Oct. 21, 2022. (JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images)

CAPE COD SHARK ACTIVITY CLOSES BEACH TO SWIMMING

Winton first revealed this population estimate last month during a new National Geographic special.

On board a boat, Izzy Lutz, an intern with the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, checks on one of the receivers in Chatham harbor that helps track sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. (David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

"Their movements are very dynamic, they trickle in and out," Greg Skomal, who leads the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries' Shark Research Program, told the outlet. "Some white sharks simply stop by on their way north while others spend more time along the Cape, likely because they have success feeding on seals."

He noted that it is important for the public to understand there are not hundreds of sharks swimming off Cape Cod beaches all at the same time.

Dr. Greg Skomal, shark researcher for Massachusetts Marine Fisheries, re-attaches a tag after a failed attempt at tagging a Great White Shark off of Chatham, Massachusetts, on Oct. 21, 2022. (JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images)

The study concluded that the need for a consistent means of assessing white shark population size still stands and said the team hoped its model could be a step towards that goal as shark populations in several regions are seemingly recovering due to protection.

Megan Winton, 38, research scientist for the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, watches as a great white shark swims next to the boat off the coast of Chatham, Massachusetts, on Oct. 21, 2022. (Photo by JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"As recovering populations return to regions where they have long been rare or absent, increased interactions between sharks and humans can create conflict and undermine public support of conservation policies. Although the overall risk posed to recreational water users remains low even at aggregation sites, the sensational media coverage that typically accompanies white shark sightings and attacks on humans generates fear and can skew perceptions of risk," the scientists warned, stating that a lack of quantitative population information can heighten this sense of risk by raising doubt about the scientific basis for management decisions and eroding public trust.

"Therefore, we view reliable abundance estimates as not only critical for management but also for navigating the complex societal conflicts that will arise when and where white shark populations recover, which will likely present the next major conservation challenge for this iconic species," the study authors concluded.