In this June 17, 2011, photo, a hot tub is on display in front of advertising for online service Costco.com at Costco in Mountain View, Calif. Costco has spent $2.3 million on an initiative that would privatize liquor sales in the state. (AP)

As the 2011 election cycle heats up, there are renewed calls to rein in the initiative process. Now 100 years old in some states, citizen initiatives have had enormous impact across the United States. This form of direct democracy has tackled everything from tax cuts to prohibition, the eight-hour work day and abortion rights. But critics contend it’s been hijacked by big-money special interest groups.

Only three initiatives gathered the required signatures to qualify for the ballot this year in Washington State. All are heavily funded by deep-pocketed interest groups.

“It’s kind of turned out the opposite, rather than a voluntary grassroots thing,” says Washington’s Secretary of State Sam Reed, “it is special interests being able to get themselves on the ballot and get these things passed.”

Reed’s office qualified one initiative backed by the powerful Service Employees International Union which would force the state to spend millions of dollars training home health care workers. The SEIU spent $1.4 million paying people to gather signatures. Another initiative is aimed at restricting highway tolls. Its campaign received more than $1 million from Kemper Freeman, a big real estate developer whose properties may suffer if widespread tolling were enacted.

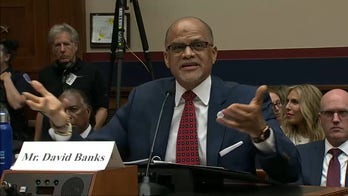

And then there's Costco. The Kirkland, Washington based retailer has spent $2.3 million on an initiative that would privatize liquor sales in the state. Since prohibition was lifted, only state government has been allowed to sell booze. Costco’s initiative would expand that to include large retailers. A similar ballot measure failed last election, but Costco is back for another try.

Amazon has also gotten into the initiative business this year. It has poured money into an initiative campaign that would undo a law passed by the California Legislature. If passed, it would scrap the law requiring online retailers to collect sales taxes in California even if they don’t have a brick and mortar presence there.

Initiative supporters say getting to the ballot is only half of the battle. They still have to get a majority of the votes on election day.

“The decision makers are ultimately the people in the initiative process,” says initiative guru Tim Eyman. “With the legislative process, it’s always the politicians.”

A growing number of politicians are now speaking out against initiatives. The California Legislature passed a bill that prohibited the paying of signature gatherers per signature. It was supported by a national group called the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center which supports progressive causes and has been a sharp critic of the initiative process.

Ken Jacobsen, a retired state senator from Washington State, is for doing away with initiatives altogether. Currently 24 states allow them. “There’s societies that failed because they had too much democracy,” says Jacobsen, “And it’s getting increasingly difficult to run the state with the initiative and referendum system.”

But initiative opponents are fighting an uphill battle. Courts have ruled against them including the Washington State Supreme Court, which ruled paying people to gather signatures for a ballot measure is a form of protected free speech. Also, governors are often hesitant to chip away at the process, fearful they’ll be viewed as taking power away from the people. California Governor Jerry Brown recently vetoed a bill that would have prevented payment per signature.

Even as special interest groups flex more muscle, the process is still viewed by most of the public as their chance to have a voice.