Biden to give first address to Congress with 'limited attendance' April 28th

Real Clear Politics White House reporter Phil Wegmann joins 'FOX Report' to discuss the president's anticipated speech

Let's get one thing out of the way first.

President Biden’s speech to a Joint Session of Congress is not a State of the Union speech.

It’s not unheard of for people to colloquially refer to a president’s initial speech before a joint session of Congress early in their first term as "State of the Union." But technically it’s not a "State of the Union." That’s because the newly-inaugurated president has only been on the job a short time.

However, President Biden has been more than "on the job" for a while now. The president's initial address to Congress comes 98 days after he was sworn in. Most recent presidents have given their first speech to Congress about a month after taking office, usually in mid-to-late February. President Reagan spoke to Congress on Feb. 18, 1981, just 29 days into his first term. President Trump spoke to Congress on Feb. 28, 2017, 39 days after taking office.

One can blame the delay for Biden’s address on a host of reasons. The pandemic still looms large. Capitol security is the other problem.

WHY BIDEN'S ADDRESS TO CONGRESS IS NOT A STATE OF THE UNION SPEECH

The last time the Capitol took on anything of this magnitude was Feb. 4, 2020. Trump addressed a joint session of Congress one day before the Senate acquitted him in his first impeachment trial.

Feb. 4, 2020 may as well have unfolded between the Mesozoic and Paleozoic periods. The pandemic gripped the planet a few weeks later, virtually shutting down the United States by late March. Insurrectionists stormed the Capitol during the certification of the Electoral College on Jan. 6, 2021. That forced congressional security officials to build two rings of security around the Capitol complex for President Biden’s inauguration. This involved deploying thousands of National Guard troops to Capitol Hill for multi-month deployments. Officials erected a pair of steep, 12-foot fences, tipped with concertina wire, to protect the Capitol.

Security officials began paring back some of the National Guard troops and removing one layer of fencing in mid-March. Then Noah Green rammed his car into the North Barricade of the Capitol, killing U.S. Capitol Police Officer Billy Evans on April 2.

USCP just arrested 22-year-old Marc Beauchamp of Henrico, Virginia, after he tried to scale the Capitol fence late Sunday night.

Congressional security officials are naturally fortifying the Capitol for Biden’s speech in ways not seen for such an address since President George W. Bush spoke to a joint session of Congress on September 20, 2001, just days after the 9/11 attacks.

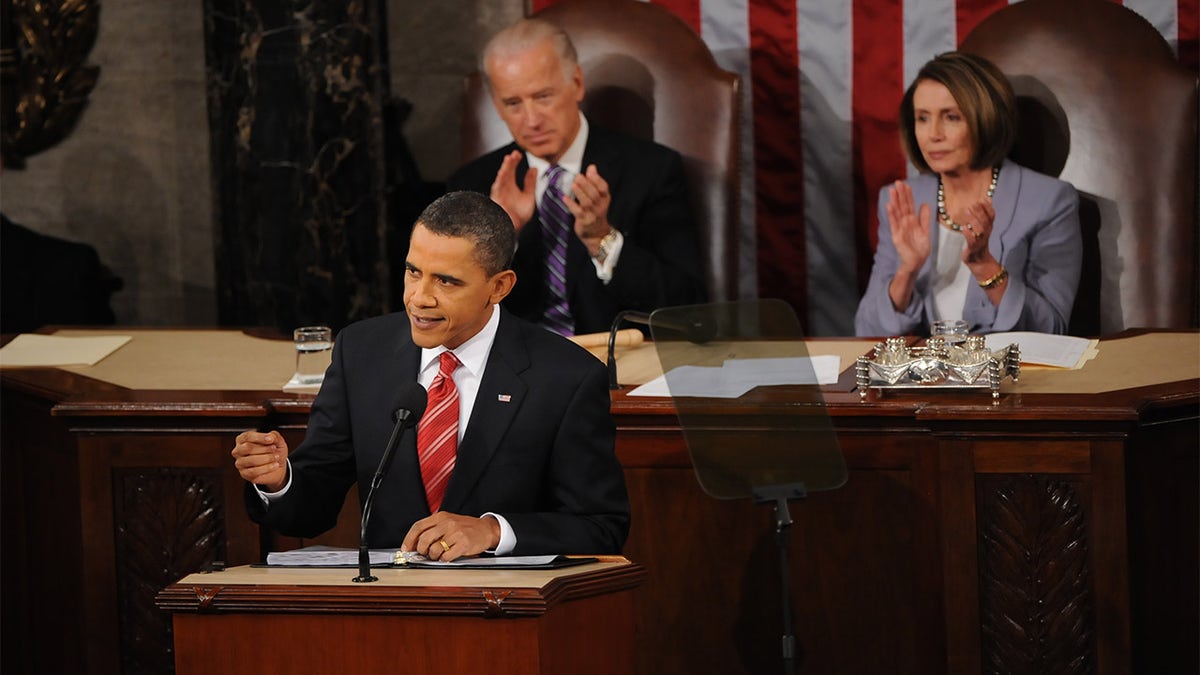

..FILE - Vice President Joseph Biden and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi behind President Barack Obama during his State of the Union address to a Joint Session of Congress on Capitol Hill on January 27, 2010 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Toni L. Sandys/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

So, this will be a presidential address before a joint session of Congress unlike others before.

Only expect a grand total of 200 people inside the chamber for the speech. That’s just a fraction of how many they usually squeeze into the chamber for a speech of this caliber. Eighty House members, 60 senators.

There are 445 fixed chairs on the House floor. They typically haul in about 140 temporary chairs. There are 660 seats in the viewing gallery above the chamber. And finally, Congressional officials can shoehorn about an additional 300 to 400 people into the chamber, standing near the back. Throw in the network TV pool and you’re staring at well over 1,600 people jammed into the House chamber. Not this time.

Not all lawmakers will come. And they won’t be allowed to camp out on the center aisle hours in advance to grab a key seat to glad-hand the president.

In fact, it’s unclear if there will be any glad-handing at all. Maybe glad-elbowing.

Members aren’t permitted to bring guests. Usually lawmakers like to show off a constituent or bring someone important on a given policy issue. None of that this year.

The House even adopted a special rule recently barring former members from coming to the floor for the speech.

U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts is the only member of the Supreme Court invited. The same with Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Secretary of State Tony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin will represent the Cabinet.

Moreover, a new face will introduce President Biden to the Joint Session of Congress. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., just swore in William Walker, the former head of the Washington, D.C. National Guard, as the new sergeant at arms. Walker succeeds former Sergeant at Arms Paul Irving. Pelosi asked for Irving’s resignation after the January 6 riot. Walker is the first Black American to hold the post. On Wednesday night, Walker will stride into the chamber, down the center aisle and declare "Madam Speaker! The president of the United States!"

President Biden speaks about gun violence prevention in the Rose Garden at the White House, Thursday, April 8, 2021, in Washington. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

When Biden speaks, he’ll do so, standing one level below two women on the dais: Pelosi, as Speaker of the House, and Vice President Kamala Harris, serving in her capacity as president of the Senate. It's the first time two women will co-preside over a joint session with the president.

And, we don’t anticipate that Biden will wear a mask.

ABC’s Mary Bruce asked White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki this week if Biden would wear a mask in the chamber. Psaki wasn’t sure, describing that as "a great question" and saying she’d consult with the President’s doctors.

PELOSI SAYS BIDEN'S JOINT SESSION OF CONGRESS IN THE HANDS OF THE CAPITOL ATTENDING PHYSICIAN

However, a senior Democratic aide tells Fox that the mask rule only applies directly to members of Congress on the floor. The House implemented the new rule for members and staff to wear masks on the floor on Jan. 4. However, former Vice President Mike Pence didn’t wear a mask when speaking from the dais when he presided over the certification of the Electoral College results on Jan. 6.

Some Republicans question whether hygiene theater is unfolding.

"When it came to impeaching Donald Trump for the second time after he was out of office, they put 100 senators in the same room, sitting just inches apart, for hours at a time, over five or six days. Apparently COVID was not an issue then," said Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., on Fox. "But now for something like this, of course we can’t have that many people in a room, sitting next to each other. So it’s kind of silly season here."

State of the Union addresses have morphed through the years. The act itself is not even a requirement. And, there’s no mandate that the president even has to give an address. Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution simply says the President "shall from time to time give to the Congress Information on the State of the Union."

President George Washington delivered the first such speech to Congress in 1790 – in New York. But President Thomas Jefferson discontinued the practice of a speech in 1801. He thought the enterprise mirrored England and a speech from the Crown. So Jefferson submitted missives to Congress instead.

The concept of a "speech to Congress" lay dormant for more than a century. President Woodrow Wilson resurrected a speech to Congress in 1913. Wilson even delivered a State of the Union speech to Congress on Dec. 2, 1918. The House had just shut down for about a month due to the Spanish flu pandemic in October. Congress reopened for business in early November. Wilson spoke a month after that.

Wilson spoke extensively about World War I, railways and international peace. But he never once mentioned the pandemic.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

President Calvin Coolidge was the first to have his speech broadcast on radio in 1923. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the first to call it State of the Union in 1934. Congress formally adopted the State of the Union vernacular about a decade later. President Harry Truman delivered the first State of the Union speech on TV in 1947. President Lyndon Baines Johnson shifted the speech to prime-time in 1964.

We think of a State of the Union speech or address to a joint session of Congress as a permanent institution in American government, cemented in tradition and protocol. But it's an organic, living undertaking. It adapts to the times.

President Biden’s speech Wednesday will look different, feel different, be different. And it likely marks the most significant change to this speech since the move to primetime television in 1964.