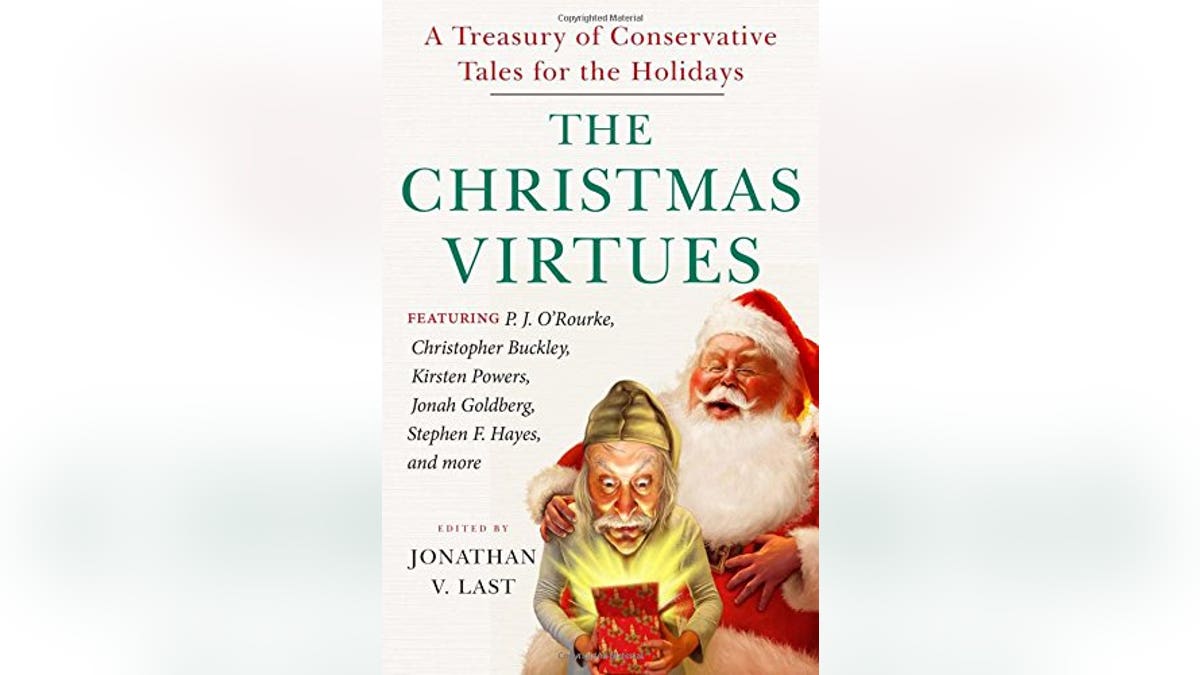

Editor's note: The following is adapted from Jonathan V. Last's "The Christmas Virtues: A Treasury of Conservative Tales for the Holidays" (Templeton Press, November 23, 2015).

I wanted a dog.

It was well before sunrise on Christmas Day 1979, and I was nine years old. I sat with my six-year-old brother, Andy, and my one-year-old sister, Julianna, on the stairs that separated us from our dreams.

My father stood at the foot of the stairs with a camera, a cassette recorder, and a mischievous smirk.

“Hello, Smiley. Where’d you get that?” said the raspy, singsong voice. “What do you have there?” It was Pop, my grandpa. He died nearly twenty years ago. His warmth was there, even in that snippet, even through the garbled audio. He was there.

The Christmas morning routine was (allegedly) born of my parents’ desire to snap a few pictures of the children before the chaos of Christmas morning ensued. But whatever their ostensible motive, we were convinced that the real reason we waited was for my father’s twisted pleasure.

He wore a look of supreme self-satisfaction as, between pictures, he thrust an audio recorder in our faces to capture our impatient answers to his aggravating questions.

“We’re going to go downstairs in a minute,” he said that morning, in a serious, reportorial tone. “But before we go down, I’d like you to tell me what you think you’re going to get for Christmas today.”

“I hope I get the whole set of basketball cards,” I said, in a high-pitched voice with a strong upper-Midwest accent. (Think Alvin the Chipmunk as a character in Fargo.)

“I think I’m going to get a racetrack,” Andy said, an octave higher. (Think Alvin the Chipmunk in Fargo after taking a hit from a helium balloon.) “And Julianna’s getting a kitchen set and a Big Wheel.”

“I really hope I get my dog,” I added.

“Well, you’re not getting a dog,” my dad replied, apparently having consulted with Santa.

Disappointed, I jumped to the kind of exaggerated conclusion kids often come to: This was going to be the worst Christmas ever.

But two minutes later, when we were released from the stairs and dashed to the fireplace to retrieve our stockings from the mantle, things began to turn around. “I got a sweatband! I got a sweatband,” I shouted excitedly.

A few minutes later, I opened a package containing a series of Alfred Hitchcock solve-your-own-mystery books.

But the best gift that year was a new pair of moon boots. “They’re big boots that keep your feet warm and you can run like crazy in ‘em,” I explained to my parents. After trying them on, I announced, “Whoa! You feel like you’re on the moon!”

I have re-created the scene for you exactly as it transpired. Because my parents kept the tapes.

I found them this past summer in a denim cassette case hidden inside a beat-up gym bag stashed in the corner of a seldom-used closet. I took the case to Starbucks one morning, along with a handheld Memorex tape player—the last one in stock at Best Buy. I popped “XMAS 1979” into the Memorex expecting to be entertained.

And I wasn’t disappointed: There was a heated debate between Andy and me about the relative merits of slippers versus moccasins. There was Julianna, just learning to talk, calling me “Feeb.” There was me making fart noises into the microphone before my dad sighed, “Don’t do things like that”—and abruptly turned off the recording.

I kept the tape rolling, only half paying attention, as I checked email and participated in a fantasy football mock draft.

And then something unexpected snapped my head back – a voice I hadn’t heard in years. “Hello, Smiley. Where’d you get that?” said the raspy, singsong voice. “What do you have there?”

It was Pop, my grandpa. He died nearly twenty years ago. His warmth was there, even in that snippet, even through the garbled audio. He was there. I heard a little more small talk and then another click.

That was all. Christmas morning was over.

And there I was, a grown man sitting in a crowded coffee shop with tears streaming down my face, and not a bit embarrassed about it.

There was nothing particularly memorable about the Christmas of 1979—I’d long forgotten the details of that morning. On a second listen, though, what stood out to me wasn’t the exhilaration of the kids, but the enthusiasm of the adults.

It certainly wasn’t, as I’d first feared, the worst Christmas ever. And it probably wasn’t the best Christmas ever. It was like all the Christmases that came before and like all the ones that followed.

More than thirty years later, the technology had changed and I was playing a different role, but the tradition was the same. I stood at the bottom of the stairs holding a video recorder as my children waited, antsy, on the edge of the top steps.

After some still photos, brief interviews, and a lot of whining (“But, Daaaaaad!”), I gave the word: “Alright.”