William LeoGrande on US-Cuba intrigues, from JFK to Obama

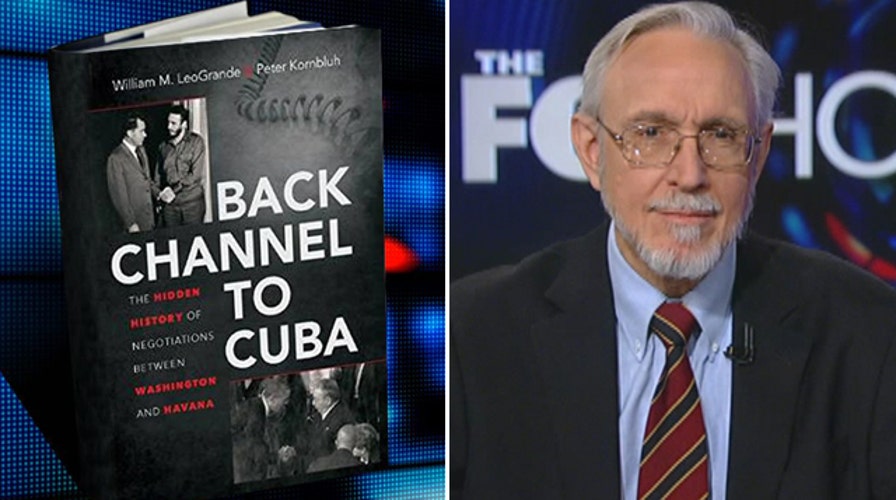

Fox News' James Rosen speaks to William LeoGrande about his book 'Back Channel to Cuba,' co-authored with Peter Kornbluh

To those public figures who champion the cause of democracy on Cuba and have long advocated for continued isolation of the Castro regime, almost as galling as President Obama's decision last month to restore full diplomatic ties with that regime was the manner in which the Obama administration arrived at the historic policy shift. In a fashion worthy of the stealth of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger when they cleared the path to Peking, the Obama White House -- specifically Ben Rhodes and Ricardo Zuniga, two key staffers on the National Security Council -- conducted secret back channel diplomacy with the Castro regime, meeting in unlikely places like Canada and at the Vatican. Prior to the president's stunning announcement of the policy shift on December 16, there was virtually no consultation with the Congress, and speculation was rife within foreign policy circles that even key figures in the State Department had been left largely in the dark.

At a recent hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator Marco Rubio, R-FL, extracted an apology of sorts from newly-minted Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who acknowledged he had failed to honor the promise he had made -- under oath -- at his confirmation hearing before the panel, when he vowed that any change in Cuba policy would be effectuated with full consultation of the committee. And Senator Robert Menendez, D-NJ, until this month the panel's chairman, told me in a recent interview that the stealthy way in which the administration negotiated with the Castro regime would lead him to approach future administration witnesses who come before the committee with a wary eye. "It's going to create a doubt in my mind," Menendez told me. "Are they either telling us the entire truth, or are they just shunned out of the process by the white House?"

It will likely provide little solace to the anti-Castro lawmakers, but American university professor William LeoGrande could tell them that such backstage machinations between American officials and the Castro regime have been occurring fairly regularly for the last six decades -- dating back to the tense days surrounding the Cuban Missile Crisis. With co-author Peter Kornbluh, LeoGrande has combed through tens of thousands of pages of declassified documents, as well as once-secret white House tapes, to produce "Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations between Washington and Havana" (University of North Carolina Press, 2014), a comprehensive history of private outreach to the Castros by successive White Houses spanning from JFK to Obama. And some of the entrants in this field surprise.

"Interestingly, Ronald Reagan opened a series of negotiations with the Cubans about a variety of issues," LeoGrande told me in a recent visit to "The Foxhole." "He talked to them about Central America; we negotiated a migration agreement with Cuba during the Reagan administration. And most importantly, the United States, Cuba, Angola and South Africa negotiated a multi-party agreement to get Cuban troops out of Angola and to provide independence for Namibia."

ROSEN: Was normalization a goal of the Reagan-era talks?

LEOGRANDE: No. For the Reagan administration, the purpose of talking to Cuba was to resolve issues that couldn’t be resolved without Cuban cooperation. Those were the ones they talked about.

LeoGrande reports that in the final days of the Nixon administration, roughly a month before President Nixon was to resign, Kissinger -- without telling Nixon -- launched a bold attempt to normalize relations with Fidel Castro, which continued under Nixon's successor, Gerald R. Ford. "That stalled when the Cubans sent troops into Angola and Secretary Kissinger was really enraged by that because it called into question the whole architecture of his policy of detente."

Under which president -- prior to the incumbent -- did the prospect of normalized relations come closest to fruition? And which recent president was most adamant in the isolation of the Castros? Visit "The Foxhole" to find out. Just don't tell Congress or the State Department that you're coming.