Did Obama miss the opportunity to kill al-Baghdadi?

'Drone Warrior' author Brett Velicovich shares his story on 'Hannity'

The U.S. military had the leader of ISIS in its crosshairs years before he became the most wanted terrorist in the world — but the bureaucratic suits in Washington let him get away.

In 2011, a secretive U.S. special operations task force was orbiting a drone above a house in Baghdad, Iraq where they had new intelligence that the notorious terrorist leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had bunkered down for a meeting with his top ISIS lieutenants. A call went out from our headquarters and then back to higher-ups in the States: we’ve got him, can we take him out?

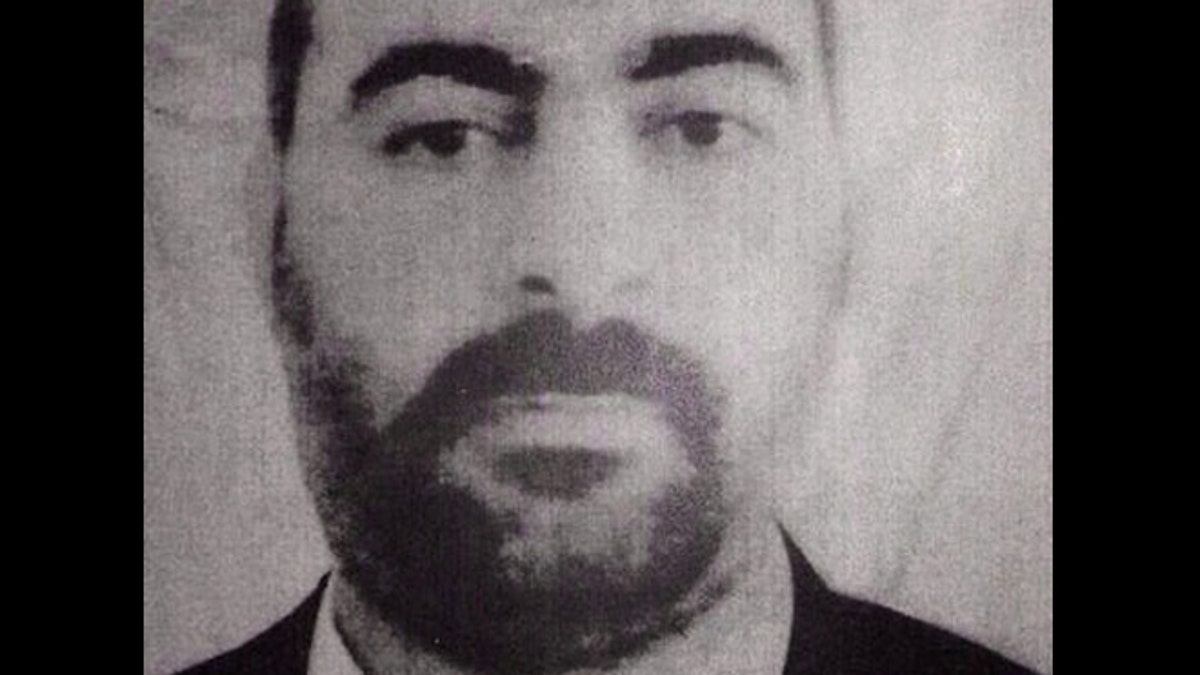

Undated file picture released on Wednesday Jan. 29, 2014, by the official website of Iraq's Interior Ministry claims to show Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, or ISIS. (AP/Iraqi Interior Ministry/File)

Our secretive targeting units had been hunting al-Baghdadi for years before he was known to the public, pushing him deeper and deeper in the shadows. Our weapon was mainly Predator MQ-1 drones equipped with two laser-guided AGM-114P Hellfire missiles, and a separate team of special operators able to finish off targets we had acquired from the ground.

Through my deployment, our team conducted dozens of raids specifically aimed to uncover him. Mostly I was chasing leads to his whereabouts, tracking his family or capturing people in his inner circle, attempts at tightening the noose around his neck. I knew just about everything one could know about him, places he visited, what he ate, who he met with, the businesses in Iraq where he laundered money. I knew more about him than his own family, I just needed the missing puzzle piece of his precise location. But every day we hunted and with each new piece of intelligence we gathered on him, I inched closer to his demise.

At one point the special ops soldiers within our task force were inside one of al-Baghdadi’s safe houses only 30 minutes after he arrived, capturing an ISIS courier in the process that al-Baghdadi had dropped off a secret letter to only minutes before. We would later use that very letter and courier to take us to the original leaders of the Islamic State, killing them days later subsequently allowing al-Baghdadi to fill the leadership gap and quickly rise to the top of the ISIS food chain.

Now in Dec 2011, the intel lead of the drone unit watched on the screens as a man, exhibiting the exact signature and description we always had for Baghdadi, arrived in a vehicle to a small concrete house in downtown Baghdad and then proceeded inside. When they zoomed in on him, there was no doubt that it was the leader we had been hunting. Walking into the courtyard of the house, heavy set and balding, other terrorists inside the compound lining up to hug the leader as he walked inside: this was the Baghdadi I knew.

Years before, our teams would have taken action without asking for a green light from Washington. A drone strike or team of special operators kicking down the door the very same night. But the State Department had changed the rules for raids as U.S. troops were told they could no longer remain in country and the planned raid on al-Baghdadi was delayed. The team was now operating under different legal authorities of law under the Obama Administration than the year before, the war in Iraq in 2011 had officially come to a close.

Before any raid or drone strike could happen, multiple levels of suits from Washington had to sign off. Days passed by, often weeks, before a strike could be put into action. Lawyers were now running the last legs of the war from behind air conditioned desks in Washington, while we were hunting down the last remaining leaders from inside the warzones. ISIS had virtually gone extinct, but the few of us doing this work day in and day out knew what was to come.

Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi warned against unauthorized social media accounts speaking for ISIS. (Reuters) (AP)

At the time, few outside our close-knit intelligence circles knew much about Baghdadi, but I knew he was one of the most dangerous terrorists in the world. The U.S. eventually put a $10 million bounty on his head.

For a long time, he had been a ghost, like a lot guys we hunted. He was surely better at hiding than any other man on our list. His operations security—OPSEC—was the best in the business. He was paranoid that we were getting close. He would be somewhere and then disappear without a trace, like a weather pattern. He knew, one little slipup and we had him. Members of his inner circle were disappearing as a result of our operations, he was seeing his closest friends and family members being captured or killed by our team’s work daily. No doubt our elite special operations task force made him the security-obsessive psychopath he is today. Paranoia of my team was what kept him alive.

Few even know the story of how he was missed. It certainly was never made public — for obvious reasons. No one wanted to talk about it anywhere in the government or military. The world’s most wanted terrorist could have very well met his maker that very night before he truly took the reins of ISIS years later.

One of the problems that night was that they were shorthanded. Our drone teams were made up of elite military intelligence personnel and other tech wizards from various agencies and partnered with a crew of Special Forces. But by 2011, the assault team had gone home. In their place, they had to rely on a local hit squad to kick down doors—a group of local Iraqis trained by a special branch within a certain intelligence agency. Which wasn’t saying much.

But the biggest problem that night was the layers of authority that had been added to our world like a badly constructed building. The drone team traditionally fell under the Department of Defense. But now that the war had moved on, the special operations task force had to get any hits cleared by both intelligence agencies and the State Department.

This was how things had changed – for the worse.

So as the drone team looked down at the house through an infrared camera, the request to raid passed from one empty suit to another, from Iraq to Washington. Calls were made to bosses multiple times, pressing them to make a move, knowing that Baghdadi was in the house at that very moment.

It was two weeks before they finally approved the mission. But by that time it didn’t matter when the Iraqis finally stormed the house. The al-Baghdadi I knew doesn’t stay anywhere for two weeks.

Who did we get that night? They grabbed up a gang of Islamic State members. And guess what those fighters confirmed? Baghdadi had 100% been there—only days before.

Guys from our team talked about it for months after. How could the suits screw up like that?

After that night in 2011, Baghdadi disappeared into Syria for months and then years again. When he came back, he was leading the charge across a broken Iraq—and ISIS was the new Al Qaeda, version 2.0. He had established an Islamic terror state and the United States is still trying to track him down to this day.

“We were so close, man, I can’t believe we missed him out of all the people we went after,” one of the guys within our task force said to me over drinks one night.

“It’s a new kind of war,” he lamented. “The rules have changed. Our hands have gotten more and more tied by the damn suits.”

Author's note: This article was approved for release by the U.S. government’s Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Excerpted from the book, "Drone Warrior: An Elite Soldier's Inside Account of the Hunt for America's Most Dangerous Enemies." Copyright ©2017 by Brett Velicovich and Christopher S. Stewart. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers