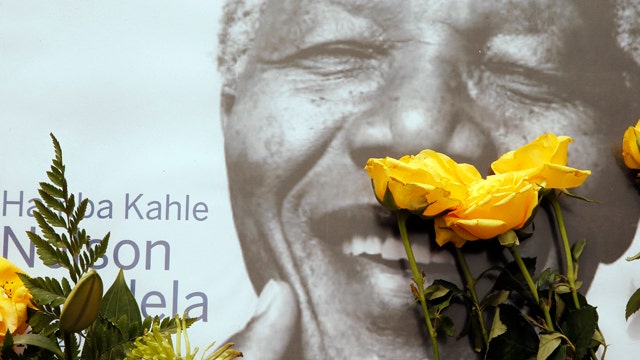

World leaders to pay tribute to Nelson Mandela

Greg Palkot reports from Johannesburg, South Africa

Standing in the rain outside Nelson Mandela’s Soweto home, the one where he lived in the years before he went to prison, I was struck by how good Soweto looked compared to the last time I was there in 1992.

The young girl signing the white wall outside the home that had become an unofficial condolence book for those making the pilgrimage wasn’t born when Mandela became the country’s first black president and took the oath of office in front of the building in Pretoria that had long been a symbol of apartheid and white oppression, a building where he would later lie in state.

As thousands of Sowetans prepared to make their way to the stadium that would host world leaders and serve as a memorial service for the father of the post-apartheid South African nation, the teenage girl’s mother described how she was pregnant with her daughter when she waited in line to cast her vote for the first time in 1994 during South Africa’s first non-racial elections.

For her daughter, apartheid was a history lesson. For us, it was a living memory.

[pullquote]

When I arrived in South Africa as a college student in September of 1989, F.W. De Klerk had just been elected president, the ANC was illegal and the petty apartheid laws were still in place.

That meant that technically black South Africans could not buy land or rent housing in white areas.

Neighborhoods were strictly segregated.

Whites for the most part did not travel to the townships, unless they were journalists or anti-apartheid activists, many of whom had faced arrest or worse until 1989.

Whites and blacks did not travel on the same buses to and from work. They lived in separate neighborhoods. Universities were starting to desegregate.

The racial pass laws had ended, but the segregation was near complete. The newspapers were still defined by the color of their readers.

The Sowetan newspaper where I was interning was the largest black newspaper in the country.

The University of the Western Cape, where I taught, was established as a so-called “Coloured” or mixed race university but had desegregated to include black students and had become a hotbed of ANC anti-apartheid activism.

I remember sitting in the living room of the South African family who was hosting me during my year off from Harvard. We watched the coverage on television as the Berlin Wall fell.

I remember thinking, “Oh no, I made a mistake. I should have gone to Germany. Eastern Europe is where all the changes were happening. That is where history is being made.”

Little did we know what was in store for South Africa over the next six months.

The changes came fast. De Klerk surprised the nation and the world when he opened the Parliament in February in Cape Town and announced that after 27 years of imprisonment, he was releasing without condition Nelson Mandela, white South Africa’s public enemy number one.

Just days later Mandela was free.

The night before the world’s most famous political prisoner was released on February 11, 1990, the apartheid government hastily distributed an updated photo of the aged Mandela to local newspapers.

The country did not know what Mandela looked like because it was illegal to publish or possess a photo of him after 1964 when he was sentenced to life in prison for sabotage at the famous Rivonia treason trial.

Mandela, who had been preserved in people’s minds as a young icon of the struggle, had aged and his white South African captors knew that they needed to prepare his supporters.

The newspapers landed with a thud that morning on the doorsteps in Cape Town and across the country.

I remember thinking Mandela looked not only old, but a little stunned in the photo. Perhaps it was the flash that hurt his eyes, which had been damaged from the dust while breaking rocks for years on Robben Island, South Africa’s Alcatraz which was five miles off the coast of Cape Town.

Later, when he became president, Mandela forbade photographers from using flash photography because it hurt his damaged eyes.

While in prison the regime realized before it was too late that Mandela represented their best hope for a post-apartheid South Africa and in the few years before he was released they began trying to prepare him for how his country had changed since 1964.

They had moved him off Robben Island to a guest house in his final years of imprisonment.

In fact, his white captors would occasionally take him on joy rides at night through the streets of Cape Town to reacclimate him. They were safe in doing so because no one knew what he looked like after 27 years.

He recalled in his autobiography “Long Walk to Freedom” how they stopped one night at a gas station in Cape Town to refuel and to buy a Coca-Cola. Imagine, he thought to himself, if the attendant filling up the gas tank knew who the passenger was seated inside the vehicle.

However, it is important to remember that “nothing was inevitable” when Mandela was released from prison to quote President Obama from the speech he delivered at Mandela’s Memorial in Soweto on Tuesday.

It was not inevitable that the country would not descend into civil war.

It was not inevitable that the white South Africans would give up power or that black South Africans wouldn’t descend into tribal war and violence as they fought for power in a post-apartheid South Africa.

A full-scale war was already taking place in the townships between various black groups, Zulus and Xhosas - Inkatha and the ANC in particular.

Mandela had evolved while in prison from leader of the armed struggle, the commander in chief of Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation, an underground group that the white South African government had outlawed as terrorists.

Mandela was not always a man of peace, but it is important to remember that he and the ANC did not turn to violence until 1961. They set off bombs that killed civilians, no doubt, but they were also facing a violent repressive regime.

Black South Africans did not have the right to vote and apartheid was the law of the land since the white Dutch-speaking Afrikaaners came to power in 1948.

In fact, when Mandela arrived on Robben Island, he had to fight for the rights of his fellow prisoners.

Apartheid, or the separation along racial lines, even was enforced in terms of how much sugar a prisoner would be given based on the prisoner’s race.

Black prisoners were given one teaspoon of sugar, Indian prisoners two. Mandela fought for equal sugar.

They compromised at 1 and a half teaspoons for everyone.

No detail was too small in terms of the fight against inequality.

On the morning of February 11, 1990 I was in Cape Town waiting with a packed crowd outside City Hall where Mandela was slated to speak.

We waited for hours. The crowd was getting anxious. After 27 years, Mandela was late being released.

Some blamed Winnie, who was said at the time to have been delayed at the hair dresser. She had come to be a symbol of arrogance and excess in the final years of apartheid.

Long forgotten on that day in Cape Town were the years that she was punished by the apartheid regime, exiled to rural South Africa, harassed by the police.

She had become a clownish figure and it was notable that after his release as soon as he flew to Johannesburg they slept in separate houses on the first night and separated and divorced not long after.

After his release, Mandela moved to the elite suburb of Houghton where a home with proper security had been prepared.

Winnie returned to Soweto to a home that she had built there with ANC funds that some had suggested at the time may have been improperly allocated.

Before leaving Victor Verster prison hand in hand with Winnie, raising his arm and clenched fist in a salute to the struggle, Mandela took a moment with his family and grandchildren before walking through the prison gate.

He was driven to a friend’s house in Cape Town out of the public glare and had to be coaxed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu to appear publicly and speak that day.

He was told that the crowds who were waiting would turn to violence, if they did not hear from him immediately.

The air of anticipation was beyond anything South Africa had ever experienced. It would be my first news story as a young journalist.

The crowd waited and waited in front of Cape Town’s city hall under perfect blue skies at the base of Table Mountain which had been tantalizingly close but unreachable for Mandela and the other prisoners on Robben Island.

An almost humorous aside broke the tension when finally a Mercedes appeared on the packed square. It inched its way forward, nudging back and forth into the knees of the waiting celebrants who had nowhere to move to make way for the car.

Who could this be? The crowd buzzed with rumors that it must be Mandela.

Finally.

Then the doors opened and a hand began waving. The crowd went wild. But the hand belonged to Jesse Jackson, who had flown to South Africa to be there for Mandela’s release.

As soon as the crowd realized this was an imposter and the man they had been waiting for was not in the vehicle that had pushed its way onto the packed square, the crowd began jumping on the Mercedes crushing the roof.

Jackson and his entourage had to be hoisted onto the balcony where Mandela would eventually appear and utter his first words in public. I will never forget those words.

“I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people.”

Mandela served to teach forgiveness. No small feat in a country where unspeakable crimes had been committed to keep a racially segregated system in place.

Perhaps his single greatest achievement was the Truth and Reconciliation commission, where anyone black or white who had committed crimes under apartheid would come and confess their crimes and receive forgiveness, a very Christian concept.

Mandela was the master of the symbolic gesture: having the white South African anthem played at his inauguration immediately after the new South African anthem, “Nkosi Sikelele Afrika,” (God Bless Africa), which had been banned as the ANC’s anthem for so many years.

Mandela reached out to the whites who worked in the president’s office and asked them to stay on his first day in office.

He went to have tea with the white widow of the founder of apartheid, Hendrik Verwoerd, to reassure white South Africans that he and the ANC had no intention of “pushing them into the sea,” as many had feared.

He reached out to the captain of the national rugby team even though the Springbok and rugby in general had been viewed as the sport of their oppressor.

Mandela wore a Springbok jersey onto the field when the South African rugby team won the World Cup in 1995, a gesture that would symbolize to white South Africans that they would remain a crucial part of the New South Africa, "the Rainbow Nation," as Mandela liked to call it.

En route to Soweto at dawn to attend the Memorial Service at the Soweto stadium, I was struck once again by the smiles and the joy and air of forgiveness that is uniquely South African.

My husband and I caught a bus from Diep Kloof in Soweto not far from Mandela’s Orlando home. We were the only whites packed onto the bus.

As soon as the bus doors closed, the singing began. Mourners wearing ANC T-shirts wrapped in South African flags began chanting and stomping singing a whole litany of apartheid-era protest songs.

The chants and the toyi-toying shook the bus and took me back to a time when it was illegal to protest, illegal to chant, illegal to fly the ANC colors of yellow and green, illegal to espouse membership in the ANC.

I smiled at how much had changed. It was pure joy on that bus.

There was the usual “Viva Mandela, Viva” and “Amandla” to which the other bus riders chanted in unison “Awethu.” Translated: “the power is ours.”

How often I had heard those chants in the townships back in 1989. They were a throw back to another time when none of this seemed inevitable.

I asked my smiling neighbor to translate what they were singing: “Mandela is calling.” It was a song that they sung when he was still imprisoned.

Today it had a whole new meaning.

When we arrived at the stadium, we walked through sheets of rain as the others danced their way and chanted toward the stadium.

I had come as a citizen, not as a journalist. A pilgrim back to a place that had particular meaning to me and my husband.

We met at this very stadium in Soweto 23 years ago in October 1989 at the first legal ANC rally.

One of De Klerk’s first acts to test the waters to see if the nation could handle Mandela’s release from prison was to release seven of Mandela’s fellow prisoners on Robben island, the founding fathers of the ANC.

Walter Sisulu was chief among them. Back then, I was working at the Sowetan, tagging along with the black journalists who had taken me under their wing as a student working in the townships.

Greg was working for the AP as a reporter. We met in the stadium inside a booth where he was looking to borrow a telephone line to file his story. There were no cell phones then, thank goodness.

As we walked through the rain toward the Mandela Memorial where four U.S. presidents were expected, I could not wait to hear the opening bars of “Nkosi Sikele, Africa,” knowing it would take me back to that day in October 1989 when the very same stadium was packed and history was made when the anthem was sung openly in public in South Africa for the first time.

Its opening notes always made me cry. God bless, Africa and God bless, Nelson Mandela.