Jared Cohen: Lincoln’s assassination nearly created a constitutional crisis

Jared Cohen chronicles the (largely unknown) series of events immediately after Abraham Lincoln was shot, including the unraveling of the conspiracy and a brief moment when it was unclear who was leading the country.

Given how loosely we throw around the term “constitutional crisis,” it is worth reflecting back on April 14, 1865, when the U.S. came dangerously close to one.

As President and Mrs. Lincoln headed to Ford’s Theatre, the first lady would later say of her husband, “I never saw him so supremely cheerful – his manner was even playful.” So surprised was she by his jubilant mood that she remarked, “Dear Husband, you almost startle me by your great cheerfulness.” “And well I may feel so, Mary,” Lincoln replied. “I consider this day, the war, has come to a close. … We must both, be more cheerful in the future – between the war & the loss of our darling Willie [their third son] – we have both, been very miserable.”

What happened next is widely known history. Booth shot Lincoln in the head, jumped off the balcony onto the stage, yelled “sic semper tyranus,” Latin for “thus always to tyrants,” and fled the scene.

ACCIDENTAL PRESIDENTS, PART 4: LESSONS IN LEADERSHIP

That same evening, Booth’s co-conspirator, Lewis Powell, invaded Secretary of State William Seward’s home and stabbed him repeatedly while he lay in bed. As part of the massive conspiracy, Booth and his co-conspirators also planned to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson.

Earlier that day, Booth ventured to the Kirkwood House, where Andrew Johnson lived in an unguarded room, since there was no vice presidential residence at the time and he had not purchased a home. Booth wasn’t interested in seeing Johnson, but he did want to inquire about his whereabouts. He asked the front desk clerk for a piece of paper and scribbled a cryptic note to be left for Johnson: “Don’t wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth.”

Another of Booth’s co-conspirators, George Atzerodt, checked into the Kirkwood House that morning, where he paid for room 126 – one floor above Johnson’s suite – in all cash. After he panicked and told Booth he didn’t want to go through with the plan, the actor threatened him, suggesting that if he tried to weasel his way out of the plan, Booth would make sure he ended up dead.

The next day, several items were found in Atzerodt’s room that would suggest he had every intention of carrying out the plan: a loaded revolver stuffed below the pillow, along with three boxes of Colt cartridges; a large-bladed Bowie knife hidden under the sheets; and a bankbook indicating a $455 deposit with Ontario Bank of Canada by a Mr. J. Wilkes Booth.

Despite the intent, Atzerodt got drunk at a nearby bar instead of murdering the vice president.

Johnson went to sleep on April 14, 1865, having no idea that the man who was supposed to kill him was drinking his sorrows away just down the block. At around 10 p.m., Leonard Farwell, the prominent former Wisconsin governor and now examiner at the Patent Office, who had also been at Ford’s Theatre that evening, began frantically pounding on the door of Johnson’s room, screaming, “Governor Johnson, if you are in the room, I must see you!”

Johnson rolled out of bed, turned on the lamp next to his bed, quickly made himself presentable, lit a candle lamp, pulled on his trousers, and came to the door. “Farwell? Is that you?” he asked. “Yes. Let me in!” For a brief moment, Johnson must have been very confused as to why someone from the Patent Office was hysterical and barging into his room in the middle of the night.

After slamming the door shut and locking it, Farwell caught his breath and explained that he had been at Ford’s Theatre and that President Lincoln had been shot! He also relayed the news that Seward had been stabbed and that the vice president’s life was almost certainly in danger. Johnson ordered Farwell to find out the condition of both men, and when he returned two hours later, the news was grim. Seward was in critical condition and Lincoln was dying.

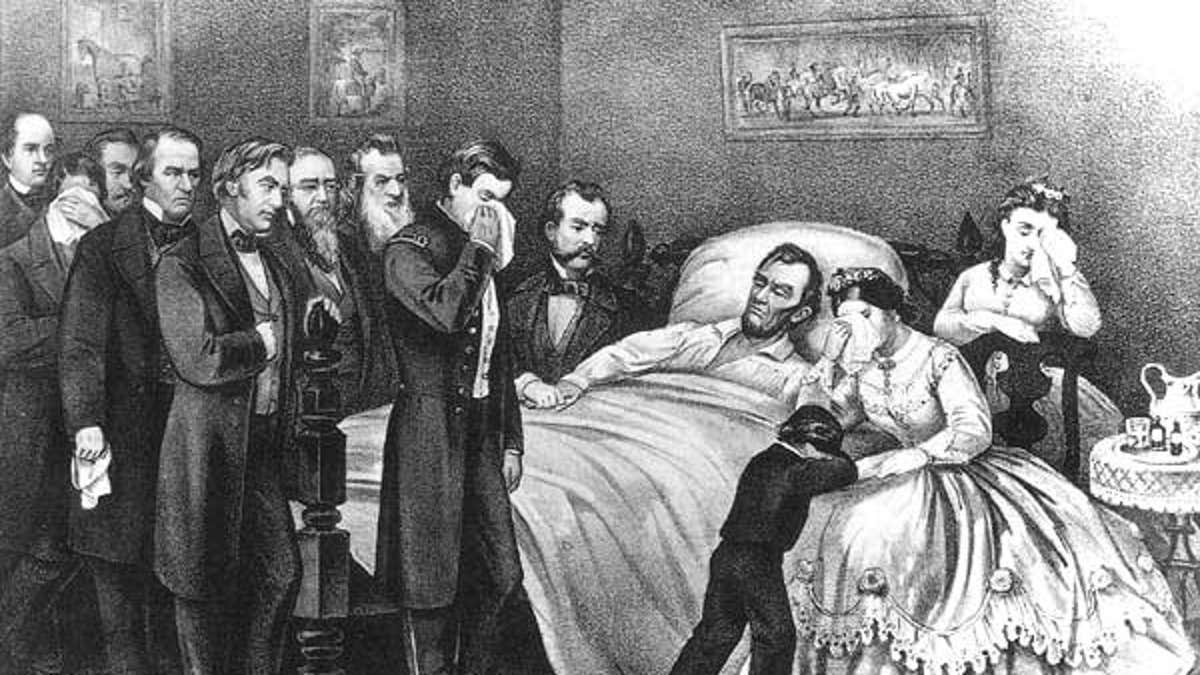

Lincoln lay on his deathbed at the Petersen House across the street from the theater with no chance of survival. Everyone knew it. But the physicians wouldn’t sit idle and instead made one last effort to save the president. In an act of desperation more than scientific intuition, they stripped off Lincoln’s clothes, spread mustard plasters on the front of his body, and covered him with heated blankets. But these attempts were useless and while the president lay dying, nobody with constitutional authority was running the country.

The official communication to Vice President Johnson, written that evening, reveals certainty about the president’s fate. In referring to his death, the first sentence of the letter initially read “this [evening],” rather than “last,” and ended with “the hour of,” leaving the time of death to be filled in by another hand. Both adjustments to the letter appear to have been in Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s hand, which is also important as he jumped the constitutional queue and unofficially placed himself in charge of the country while Lincoln was incapacitated.

Nobody seemed to question Stanton’s temporary assertion of authority, not even the vice president. Johnson, Farwell, and an Army major named James O’Beirne made their way from Kirkwood House to the Petersen House, where Johnson encountered the cabinet for the first time since his drunken inaugural. He remained for about 30 minutes, which must have been painfully discomforting, but stood mostly off to the side, until Charles Sumner politely asked him to leave, explaining that his being there agitated Mrs. Lincoln.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

It seemed not to sink in with anyone in the room that Andrew Johnson was about to become president, not even Johnson, who acknowledged Sumner’s request and quietly left. Should Johnson have been in charge at this time? Was that his constitutional obligation? In the context of 1865, it really wasn’t clear. Given there was no chance of Lincoln’s recovery, it would seem that Johnson should have taken the oath right then and there. By doing so, the powers of the presidency would be vested in him.

Many years later, Johnson would recall the gravity of the situation that lay before him. “It was evident from the first that Booth’s shot would prove fatal,” he remembered. “I walked the floor all night long, feeling a responsibility greater than I had ever felt before more than one hundred times. I said to myself: What course must I pursue, so that the calm and correct historian will say one hundred years from now, ‘He pursued the right course’? I knew that I would have to contend against the mad passions of some and self-aggrandizement of others.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE IN JARED COHEN'S "ACCIDENTAL PRESIDENTS" SERIES, AND KEEP VISITING FOXNEWS.COM/OPINION FOR MORE BOOK EXCERPTS.

Excerpted from "Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America" by Jared Cohen (Simon & Schuster, April 9, 2019)