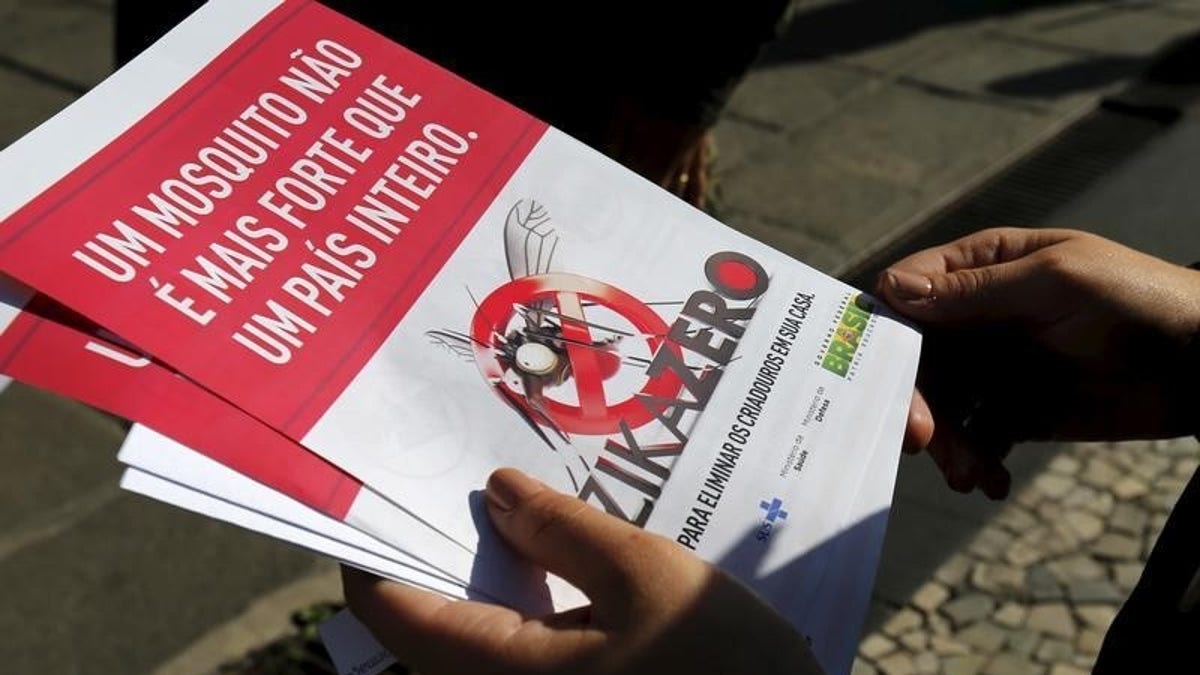

A Brazilian Army soldier shows pamphlets during the National Day of Mobilization Zika Zero in Rio de Janeiro (Copyright Reuters 2016)

LONDON – In what experts describe as another piece of evidence linking Zika with the risk of birth defects, researchers on Wednesday reported finding the virus in the amniotic fluid of two pregnant women whose fetuses were diagnosed with microcephaly.

In a study in the Lancet Infectious Diseases journal, the scientists said their finding suggests Zika virus can cross the placental barrier, but does not prove it causes microcephaly, a condition in which babies are born with abnormally small heads.

More research is needed to understand the link, they said.

"This study cannot determine whether the Zika virus identified in these two cases was the cause of microcephaly in the babies," said Ana de Filippis, the doctor who led the study at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

"Until we understand the biological mechanism linking Zika virus to microcephaly, we cannot be certain that one causes the other."

Many scientists believe Zika, a mosquito-borne disease that is currently sweeping through the Americas, may be a risk factor for microcephaly in newborns, as well as for a serious neurological disorder in adults called Guillain-Barre syndrome.

The World Health Organization has declared the Zika epidemic spreading from Brazil a global public health emergency and called for urgent studies to establish with its association with rising number of cases of suspected birth defects can be proven.

De Filippis' study noted that the number of suspected cases of babies with microcephaly in Brazil in 2015 has increased twenty-fold compared with previous years. At the same time, Brazil is reporting high numbers of Zika virus infections.

Babies born with microcephaly are at risk of incomplete brain development.

The condition has previously been linked to a range of factors including genetic disorders, drug or chemical intoxication, maternal malnutrition and infections with viruses or bacteria that can cross the placental barrier such as herpes, HIV, or other mosquito-borne viruses such as chikungunya.

For this study, de Filippis' team investigated the cases of two women, aged 27 and 35, from Paraiba in northeastern Brazil.

The women had symptoms of Zika infection - including fever, muscle pain and a rash - during their first trimester of pregnancy. Ultrasounds taken at approximately 22 weeks of pregnancy confirmed the fetuses had microcephaly.

The researchers took and analyzed samples of amniotic fluid at 28 weeks of pregnancy. While the women's blood and urine samples tested negative for Zika, their amniotic fluid tested positive for the virus genome and for Zika antibodies.

"Details of the Zika virus being identified directly in the amniotic fluid of a woman during her pregnancy suggest ... the virus could cross the placental barrier and potentially infect the fetus," de Filippis wrote.

Jimmy Whitworth, a Zika expert and professor of international public health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said the findings "strengthen the body of evidence" pointing to Zika as a cause of microcephaly in Brazil.

But he noted that while studies of this sort can show associations, they can't show direct causation.