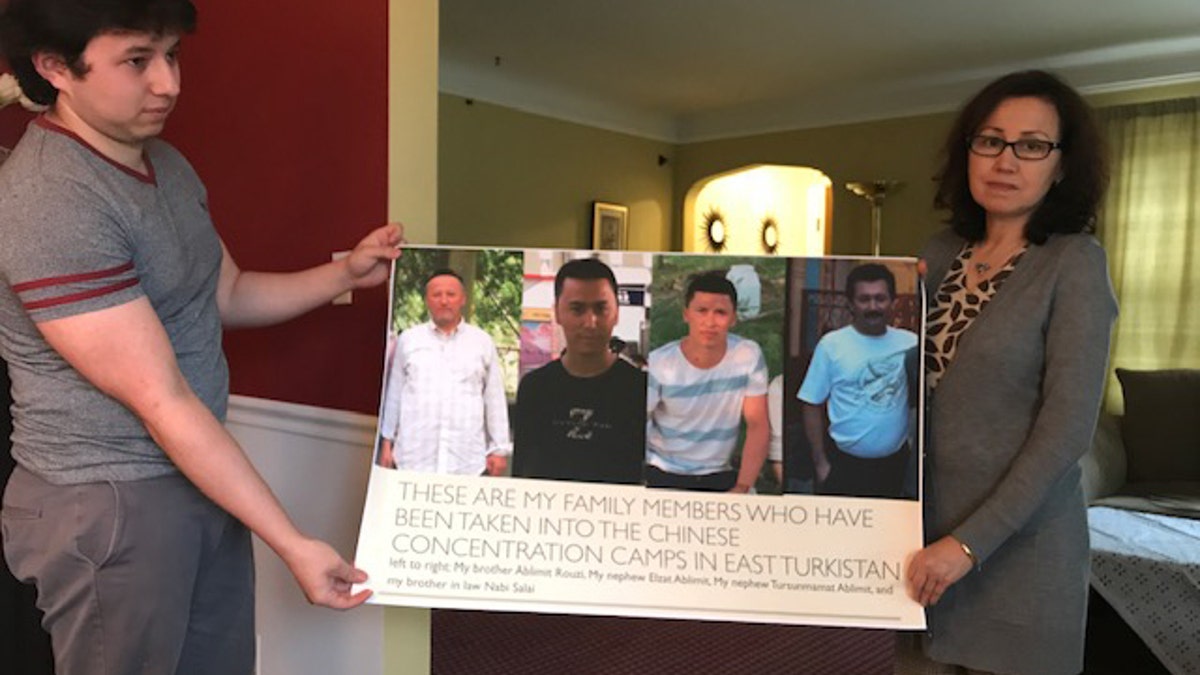

Inside their Ohio home, Sainawar Rouzi and her son Nisham, 23, roll out a poster they had made to show the names and faces of their family members they believe to have gone missing into the dark abyss of shadowy “concentration camps” in China. (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

CINCINNATI, Ohio – They may be sitting some 6,800 miles away, but the pain of one Uighur family in exile remains just as visceral and raw as it was back in their homeland.

“My family never did anything wrong. They only ever contributed to the government, and never did anything illegal or committed a crime. Now they have disappeared or live in fear – waiting for a knock at the door,” Sainawar Rouzi told Fox News, in an interview at her home. “We all live in prisons in our mind, wondering how this has happened to our people. I have to be the voice for my family, for the Uighurs. They have no voice.”

Rouzi and her son Nisham, 23, rolled out a poster they had made to show the names and faces of family members they believe have gone missing in “concentration camps” for Uighurs that have been set up in China. And those family members who weren't taken away, she said, received a dreaded late-night visit from Chinese officials warning them to stay quiet, after a video appeared of her at a protest rally outside the White House earlier this year.

“They are still being threatened to try to stop me from speaking,” Rouzi lamented.

Somewhere between one and five million Uighurs, also sometimes spelled Uyghur, have been sent off to what the Beijing government officially refers to “re-education camps” - but have been classified by many others as forced labor or concentration camps.

TRUMP DELAYS CHINA TARIFF HIKE, ANNOUNCES XI SUMMIT, CITING 'SUBSTANTIAL PROGRESS' IN TRADE TALKS

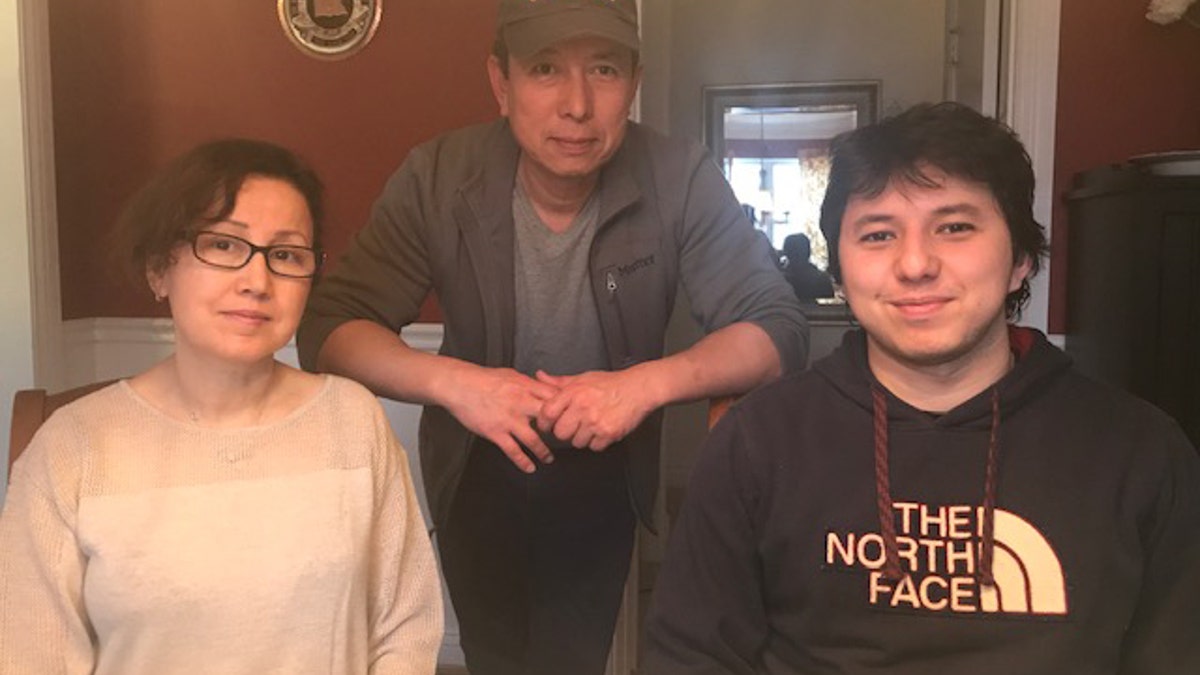

Rouzi, who has been in the U.S since 2001, and was a medical doctor in China – now practices as a nurse while her husband Nijat Kadeer – also a doctor – works as a local medical researcher. They fled with their only son after being accused of “treating terrorists” – simply for tending to other ill Uighurs, she said.

They have been unable to reach many of their family members for more than two years, in an area they refer to as Eastern Turkistan. The Chinese government calls the area the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. The size of Alaska, the massive area is swathed by vast deserts in the nation’s northeast.

Sainawar Rouzi, who has been in the U.S since 2001 and was a medical doctor in China – now practicing as a nurse while her husband Nijat Kadeer – also a doctor – works as a local medical researcher. They fled with their only son after being accused of “treating terrorists” simply for tending to other ill Uighurs.

Many Uighurs pretend they don’t know who they are when they attempt to call relatives. Sometimes the phone line goes dead. Some loved ones have simply disappeared into the unknown, according to the testimony of several Uighurs-in-exile interviewed by Fox News.

Even family members who haven’t been locked away say they aren’t free to travel, speak their language, name their children, or practice their faith. While China’s Constitution mandates freedom of religion, the minority Uighurs – most of who are secular or practice a generally relaxed form of Islam – say they are being targeted not only because of their faith, but because they have long sought their provincial independence from what they consider “Chinese occupation.”

But Uighur activists abroad aren’t relying on Muslim-majority countries to champion their cause. It’s the United States, and leaders in the West, who are pressuring China to stop what has been largely deemed gross human rights violations.

In this Nov. 4, 2017 file photo, Uighur security personnel patrol near the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar in western China's Xinjiang region. China's northwestern region of Xinjiang has revised legislation to allow the detention of suspected extremists in "education and training centers." (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File)

From the State Department to members of Congress to the Office of Vice President Mike Pence, U.S. officials and elected representatives have frankly raised the issue with China numerous times - even threatening action if China doesn't close the secret detainment facilities.

In December, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called out Chinese authorities for “likely detaining, at least, hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in internment camps in Xinjiang.” The month before, Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) introduced the bi-partisan Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act in response to “the gross violations of human rights in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, including the mass internment of over one million Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities, as well as China’s intimidation and threats against U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents (LPRs) on American soil.”

The legislation, signed by 14 senators on both sides of the party divide, has been referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations.

“The United States must hold accountable officials in the Chinese government and Communist Party responsible for gross violations of human rights and possible crimes against humanity, including the internment in ‘political re-education’ camps of as many as a million Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim minorities,” Rubio said in a statement. “I’m proud to lead this important initiative that elevates the current crisis in Xinjiang, puts forth policy options to address it, and signals that we will not tolerate Chinese government intrusions on American soil.”

AGENCY WORKS TO END IRAN'S MANIPULATION OF IRAQ, TEMPER CHINA'S GROWING INFLUENCE

Other Western nations have also been stepping up and speaking out. Ambassadors from 15 nations including Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and the European Union joined forces late last year to force a meeting with Xinjiang Region Communist Party Secretary Chen Quanguo, to address the alleged human rights abuses. While the meeting took place, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by saying they “reject the interference in China's internal affairs with malicious intentions.”

At the UN, meanwhile, Germany has bluntly called on China to “end all unlawful detentions in Xinjiang,” while Iceland and Japan have also raised red flags about minority rights in the region.

Many Uighurs and human rights groups insist that the clampdown has worsened under the reign of Chinese President Xi Jinping. Earlier this month, a coalition of rights groups, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, banded together to request the UN launch an investigation into China’s large-scale detentions.

But the silence from Muslim-majority countries has been mostly deafening, Uighurs and activists say.

“There is a certain expectation that Muslim-majority countries would naturally lend support to Uighurs and criticize China, but we haven’t seen this. And I don’t expect we will see this, given China’s economic ambitions with the Belt and Road Initiative, however successful the plan may or may not be,” said Peter Irwin, the spokesman for the Germany-based World Uyghur Congress rights group.

Chinese investment in the Middle East is extensive, and growing. In 2018 alone, China invested some $25.5 billion in the region, according to a tracker by the American Enterprise Institute. Between 2009 and 2018, meanwhile, China invested some $150 billion, across 15 area countries.

Salih Hudayar – political affairs officer for the East Turkistan National Awakening Movement, a Washington-based human rights groups devoted to the independence of the region – argued many countries are staying silent over fears of jeopardizing investments.

“Many Muslim-majority nations are seeking China's investment. Pakistan is seeking to further develop CPEC, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, and so Pakistan's government officials have bitten their tongues about the Uyghurs' plight,” he said. “The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is seeking to increase state-owned Saudi Aramco's oil business with China, and so they have been silent.

"Egypt's economy has suffered greatly over the past several years, and they're hoping to attract China's loans and investments, so they're also hesitant to criticize China," he added. "The number of Chinese firms operating in Turkey hit 1,000 last year, according to data from Turkey's Economy Ministry, and so Turkey has only recently and reluctantly spoken out. The list goes on and on.”

Salih Hudayar – political affairs officer for the East Turkistan National Awakening Movement, a Washington-based human rights groups devoted to the independence of the region – argued many countries are staying silent over fears of jeopardizing investments.

Turkey, an overwhelmingly Muslim-majority country, is one of few such nations to occasionally speak out about the alleged Uighur oppression. Turkey used its UN platform to call on China to do more to protect the Uighurs, and freedom or religion. But Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu did not specifically mention the camps. Britain was the only other county in the 47-member Human Rights Council to state its “deep concern” for the oppression.

Along with economic interests, activists assert that Chinese government concerns over their own questionable human rights records also plays a pivotal role in the silence.

“In some states, their own governments do not have ideal human rights protections themselves, so the people would be hard-pressed to speak out fervently about a group with no obvious connection aside from faith,” Irwin explained.

CHINA'S HUAWEI SPY RISKS THREATEN U.S DIPLOMACY ABROAD

Alfred Erkin, a 21-year-old Uighur based in Virginia – who dropped out of university studies after his family at home disappeared and he could no longer afford the tuition – surmised that some countries also may be concerned with retaliation against their own citizens.

“In less than a month, 13 Canadians have been detained in China since the high-profile arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou on Dec 1,” he said. “Even one Canadian man sentenced to death in mid-January.”

Wanzhou was detained late last year at the request of U.S authorities, who are expected to seek her extradition on charges of violating sanctions with Iran amid growing concerns over the tech giant’s spy capabilities.

Uighurs living in Turkey and Turkish supporters, some carrying flags of East Turkestan, the term separatist Uighurs and Turks use to refer to the Uighurs homeland in China's Xinjiang region, gather outside the Thai consulate in Istanbul, early Thursday, July 9, 2015. A group of protesters stormed the consulate overnight, smashing windows and breaking into the offices (AP Photo) (The Associated Press)

But Muslim-centric governments aren’t the only ones staying silent. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) has said nothing on the matter, not even during a review of China’s human rights record at the UN last November. The OIC did not respond to a Fox News request for comment.

Some Uighurs point to atrocities involving other Muslim minorities – such as the Rohingya Muslims in Buddhist-dominant Burma – which has attracted a chorus of condemnation from governments and activist groups, including the OIC. And some of those Uighurs feel betrayed by.

Last August, the UN declared it was “deeply concerned” by the emerging reports of Uighur detention facilities. Nonetheless, China remains a member of the 47-member Human Rights Council.

Furthermore, the Vatican – often outspoken on allegations of global human rights violations against all minorities – did not respond to a comment request. Last September, the Vatican and China inked a milestone– albeit controversial – deal in which Beijing agreed to recognize Pope Francis as the leader of Chinese Catholics in a trade for Francis distinguishing two bishops in China who were delegated without the Holy See’s consent. No public comment was made by the Vatican on the plight of the Uighurs.

Nonetheless, the Chinese government has staunchly denied any wrongdoing or violations. When word of the camps started to gain momentum last year, the Chinese government denied their existence. That stance was later changed, admitting that the camps did exist but that they were under the guise of “re-education camps” endeavoring to stop any Muslim extremism from flourishing and under the guise of national security interests.

Sainawar said that after she gave testimony at a protest rally outside the White House earlier this year, her family received that much-dreaded door knock from authorities and were subsequently cautioned to stay quiet.

Beijing has subsequently highlighted a reduction of attacks since the camps seemingly surfaced in 2016 as confirmation of their strategic success. And it is reported to be ramping up its diplomatic outreach as the controversy over the camps, by offering a number of foreign diplomats and journalists from Muslim-majority nations the chance to visit the area on a tightly controlled trip.

According to a Reuters report last week, Beijing has become “increasingly worried about the overseas backlash against the camps, especially threats of U.S. sanctions, and has sought to counter that with a public push for a friendlier narrative.”

But activists like Irwin caution not to be deceived. He acknowledged that while the U.S. government has “taken the firmest line so far,” much more can and should be done.

“The best and most effective approach is to continue to call attention to the abuses as a first step. If China feels no cost for their abuses, they will continue in the same way,” he said. “We have to continue to press China, not for the sake of anything except the most basic human rights protections that we demand in the West.”