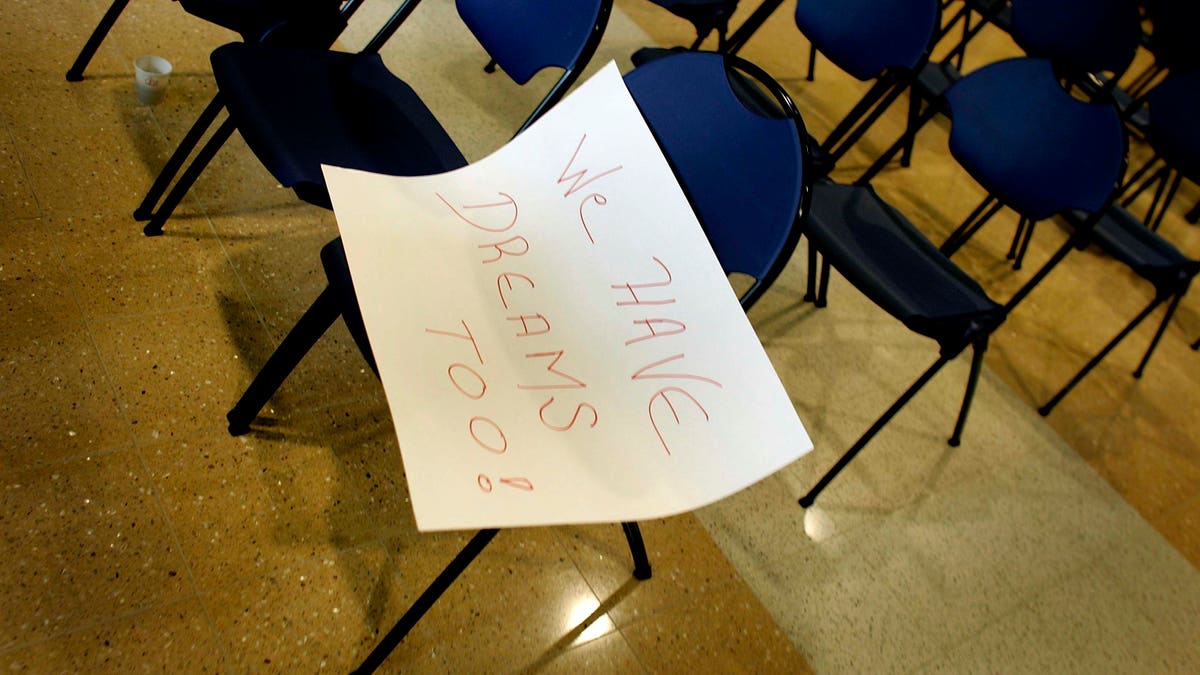

MIAMI - MARCH 12: A sign with the words, " We have dreams too!", lays on a chair after a press conference to announce The American Dream Act March 12, 2007 at Florida International University in Miami, Florida. The bill, if passed in the United States Congress, would allow for undocumented immigrant students to obtain in-state tuition as well as permit those students, along with those serving in the military, to obtain a green card and legally remain in the United States. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images) (2007 Getty Images)

As tenth grader Violeta Gómez-Urive sat in her house while her older brother Jesús filled out college applications, they stumbled across a shocking revelation after getting to the part that asked for a Social Security number.

They did not have one.

All the years they had proudly recited the Pledge of Allegiance in their classrooms, watched Saturday morning cartoons, and shopped at local malls, they had been undocumented.

“At the beginning it felt confusing, because I fully didn’t understand what it really meant,” Gómez says.

Gómez and her brother were brought into this country by their mother in 2000 when she was 15- years-old on a tourist visa.

“I thought I had a Social Security number like everyone else,” she says. “I knew I wasn’t born here but in my heart I knew I was American.”

The Gómez siblings’ lack of awareness of their unlawful status is common among undocumented Latino families.

Often fearing persecution and deportation, their parents keep the undocumented status a secret from their children. It often is revealed, sometimes accidentally, as late as their senior year in high school—typically during the application process for college or the military.

Like many undocumented students, Gómez does not qualify for most financial aid, driver’s licenses, and cannot travel outside the United States. Many give up hope of attending college after graduating from high school and costs are the main reason for it.

“I assumed I was going to have to go to community college (once I found out) but I felt very sad and very upset because I knew I had the grades and capability of going to a four year school,” she says.

Those who do manage to graduate from college then find many doors firmly bolted when they try to find work.

Some undocumented kids like Melissa García Valez, 18, who wants to be a social worker, understand that they don’t have papers but have no idea that there was anything ‘different’ about it. The consequences of being an undocumented immigrant didn’t hit Valez until a casual conversation with her guidance counselor and college advisor, Gwen Altman, on a bus ride from a college trip.

“I thought I was like everyone else,” Valez says. “All I was ever told was that I couldn’t travel outside the country, I was never told that I was different or had any limitations.”

Valez is a freshman honors student at Lehman College of the City University of New York and she says it was Altman who was instrumental in helping her get to college.

“It is very hard to get scholarship money for undocumented students,” says Altman. “I did a lot of advocating for her, spoke to many reps…reaching out to anyone I thought had some sort of influence.”

While fear keeps undocumented immigrants from telling their teens the truth about their status, Altman feels it’s best to unveil the secrecy over their illegal status.

“Absolutely, they should tell their kids earlier because it is part of who they are and part of some of the obstacles they are going to face for the rest of their lives, “ says Altman, a guidance counselor and college advisor at the Richard R. Green High School in New York City. “If the students know earlier, they will know from the beginning how important it is for them to work harder and get good grades.”

There are an estimated 65,000 undocumented students who graduate from America’s high schools each year. A controversial bill, known as the DREAM Act, currently in Congress, would allow these students to get on a path to U.S. citizenship if they attend college or serve in the military for at least two years.

Proponents of the DREAM Act say undocumented children should not be penalized for the decision of their parents to live here illegally.

“My question is: how do you tell a one year old child they are a law breaker?” asks Cid Wilson, Vice Chairman of the Board of Trustees at Bergen Community College. “Find me anywhere in the penal code that when one person breaks the law we are going to penalize your child, not even murder, there is nowhere else in the code that does that. ”

But those who oppose the DREAM Act disagree.

“We are not punishing the children for the illegal acts of their parents we are merely not rewarding them for the acts of their illegal alien parents,“ says Bob Dane, the spokesman for the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). “Even if the kids only entered as a result of their illegal alien parents, it’s the parents that are rewarded when their kids are granted amnesty.”

Dane adds that the Act would encourage more illegal immigration and is fundamentally unfair to those who come here legally.

“Ideally, the thing to do would be to return back to their home country and have them apply legally for an F1 student visa,” Dane says.

One of the most recent and prominent spokesmen of the fight for the DREAM Act is Fresno State University senior and student body president, Pedro Ramírez.

He was exposed in November when an anonymous e-mail about his undocumented status was sent to his college newspaper. Shortly after, Ramírez publicly admitted his illegal status.

Ramírez had no idea about his status until his senior year in high school. His parents broke the news to him after he began showing interest in serving in the U.S. military, he says.

“A lot of my friends were joining the military or the National Guard and it inspired me,” Ramírez says. “One day I got some pamphlets in Spanish, and when I showed them, they [parents] told me I couldn’t do it because I was undocumented.”

So how did he feel when they let him in on the big family secret?

“I was shocked and I was mostly confused because I didn’t know what I was going to do and I didn’t know what the effects were going to be,” he says.

He wishes he would have known sooner, but he doesn’t hold it against his parents for keeping the family secret to themselves.

“I think it was to protect me. They didn’t want me to talk about it. My parents didn’t want me to go tell my school teacher and everyone I know,” he explains. “We do live in a conservative area here in the Central Valley [of California].”

As for Gómez, she doesn’t feel resentful towards her mother for having kept this family secret from her.

“It was just something my mom purposely didn’t talk about," she says. "It was never brought up by my schools either, so I guess she thought everything would be ok.”

In terms of her future and the future of other “Dreamers,” Gómez, hopes people like her and Ramírez will continue to speak out about their status.

Today, Gómez, 25, waits tables to pay for her education. She has received her associate’s degree and is currently in her third year of the bachelor’s program at Hunters College, also a CUNY school. She dreams of being a forensics accountant one day - litigating and working, ironically, for the US government – perhaps even in the FBI or the IRS.

“The more you hold yourself back, the more ability these other people have to be against you,” she says. “At some point I was afraid and I was alone but it’s always better to give it a try, to give it a fight and to encourage others who are afraid.”