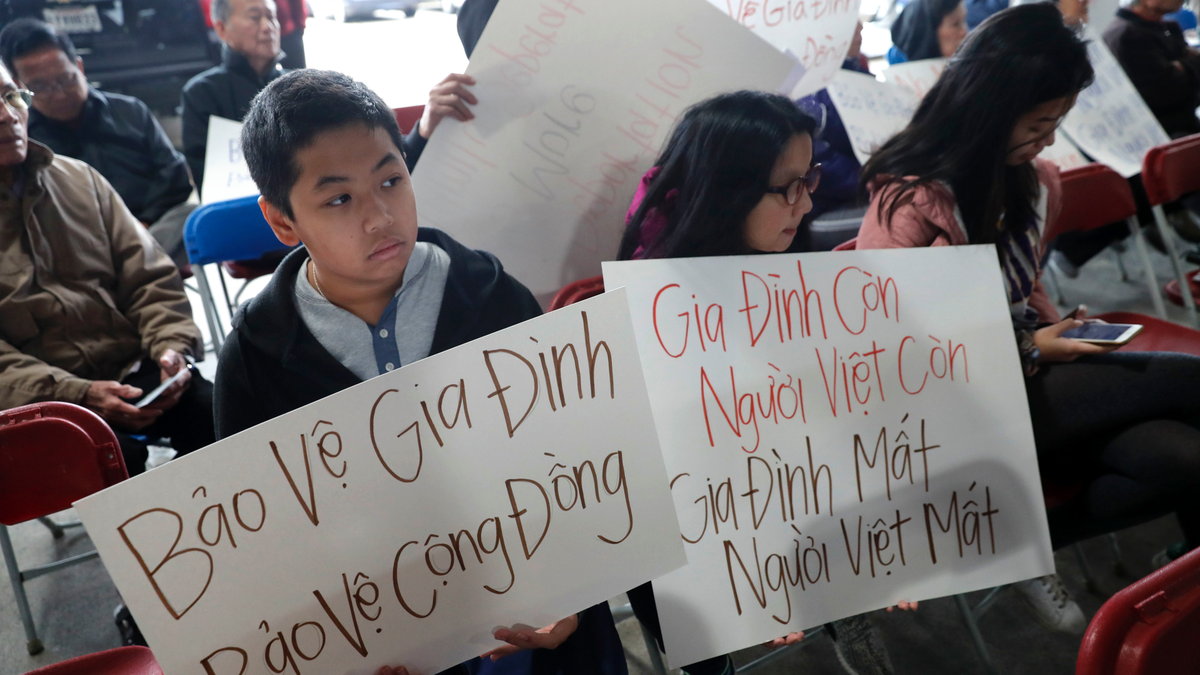

Bill Nguyen, 12, and Jade Nguyen, 9, hold signs at a rally protesting President Donald Trump's deportation policy to deport Vietnamese refugees, at the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church in New Orleans, Thursday, Dec. 20, 2018. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

NEW ORLEANS – Members of the Vietnamese community are protesting what they say are efforts by the Trump administration to deport certain Vietnamese immigrants, an effort they say is a betrayal of refugees who fled war-torn Vietnam.

Advocates say the administration is trying to deport Vietnamese immigrants who came to the U.S. before 1995 and have been given a final order of removal by an immigration judge — generally because they committed a crime — even though the groups argue they are protected from deportation by a 2008 agreement between the U.S. and Vietnam. The Trump administration argues that the agreement does allow them to be deported, the affected immigrants have been ordered to leave by a judge and Vietnam should take them.

In many ways, the Vietnamese situation is a special case. The reality for most immigrants who commit a crime is that they get deported. But the Vietnamese issue has touched a nerve in part because of the longstanding ties with a community that often fought side by side with Americans and paid a high price for that commitment.

The ongoing debate has concerned many in the Vietnamese community who came to the U.S. after the 1975 fall of Saigon and worry they could face persecution in Vietnam — a country where they have few if any relatives or connections.

"These folks already did their time. It's not fair for something like this to come back and bite them," said Minh Nguyen, who heads the community organization VAYLA New Orleans. The city has a large Vietnamese community, many of whom are refugees or children of refugees. "They have every right to be here. They were protected. They are permanent residents. ... They never had to worry about being deported and now all of a sudden they are at risk."

The debate stretches back months. A group of Vietnamese immigrants filed a lawsuit in February saying the administration was holding Vietnamese immigrants and intending to deport them even though the activists say they were protected under a 2008 agreement between the U.S. and Vietnam. The agreement set up parameters for deporting Vietnamese citizens who came to the U.S. after July 12, 1995 — the day the two countries re-established diplomatic relations — but advocates argue it bars pre-1995 immigrants from being deported.

A 2001 Supreme Court ruling also limits the amount of time immigration authorities can detain someone to six months if there is no reasonable prospect of the person's home country taking them back.

Phi Nguyen, one of the attorneys representing the Vietnamese immigrants, said in a fall court filing that the Department of Homeland Security said it no longer believed Vietnam would take back pre-1995 Vietnamese immigrants and was beginning to release those in its custody. Although officials said they would continue to negotiate with Vietnam, Nguyen said advocates breathed a sigh of relief as the immediate risk seemed to lessen.

Then in December, they heard that the U.S. and Vietnam were meeting again to discuss the issue, she said, raising concerns again. Elaine Sanchez Wilson, a spokeswoman for the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center says they were told by a congressional aide who did not want to be identified that the two sides were meeting to discuss the return of Vietnamese citizens subject to final orders of removal.

"We are gravely concerned with the Trump Administration's cruel effort to deport Vietnamese refugees who should have our country's protection," the organization's head, Quyen Dinh, said in a statement.

Advocates have held events in Southern California and New Orleans to publicize the issue and were planning an event in Houston on Thursday evening. More than 20 members of Congress signed a letter last week saying that sending Vietnamese refugees back would tear families apart and disrupt refugee communities in the U.S.

The State Department confirmed there was a meeting between U.S. and Vietnamese officials on Dec. 10 and 11 but declined to say what it was about. Brendan Raedy, a spokesman for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said in an email that the department does not comment on the details of diplomatic negotiations.

But the administration made clear that it does believe it has the right to deport Vietnamese immigrants who came to the U.S. before the key 1995 date.

Raedy said the 2008 agreement governs deportations for people who arrived after the 1995 normalization date but also allows each side to "maintain their respective legal positions regarding individuals who arrived prior to July 12, 1995."

"The U.S. position is that every country has an international legal obligation to accept its nationals that another country seeks to remove, expel, or deport," he wrote.

He said 11 Vietnamese nationals who arrived in the U.S. before 1995 have been removed to Vietnam since July 2017. But potentially thousands more people could be affected.

As of Sept. 17, 2018, there were 8,634 Vietnamese nationals in the United States with a final order of removal, 7,781 of whom were convicted criminals, he wrote. There were also 71 Vietnamese nationals in ICE detention with a final order of removal, 66 of whom were convicted criminals, he said.

Vietnam is one of nine countries the U.S. considers uncooperative in accepting the return of their nationals ordered removed from the United States, he wrote. That is down from a high of 23 in July 2015, he said.

___

Follow Santana on Twitter @ruskygal.

___

Associated Press writer Matthew Lee in Washington contributed to this report.