OMAHA, Neb. – Supporters of a teacher whose Omaha Catholic school contract will not be renewed because of his same-sex relationship say the school is discriminating against him based on his sexual orientation.

But experts say the school has not violated Omaha's 3-year-old anti-bias ordinance protecting gay and transgender people because the ordinance has a religious exception, and a lawsuit would probably not succeed.

Skutt Catholic High School rescinded its offer to renew the contract Matt Eledge, an English teacher and speech team coach, after learning he planned to marry his same-sex partner, saying that would violate church tenet in breach of his contract, according to Kacie Hughes, a close friend of Eledge's and assistant Skutt speech coach. The school later said he could return to the school, but only if he ended his same-sex relationship.

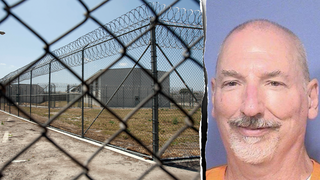

Eledge, 28, confirmed that his contract at Skutt has not been renewed. He's taught at the school since 2010, and the speech team he coaches just won its fourth straight state championship.

"Whatever happens, I love Nebraska and I love my job. I love working here," he said. "I want to do the right thing, but I don't want to say anything that would hurt my job or anybody I care about. I'm scared and unsure and fearful. I'm just trying to finish out the year at this point."

Hughes, a 2012 graduate of Skutt, said Eledge was told by his bosses that if he told his students he was gay, "he'd be fired on the spot," she said.

"Catholic schools in general allow teachers to be divorced without an annulment, or let teachers be on the pill or let men get a vasectomy ... there are so many examples," Hughes said. "You don't do this to anyone else except for him, because he's gay."

Omaha Archdiocese Chancellor Tim McNeil said that's not true. There have been single, pregnant teachers and those who've divorced and remarried outside the Catholic church who have lost their jobs, he said.

He also acknowledged that plenty of teachers get away with breaking church tenet, saying the archdiocese essentially has a "don't ask, don't tell" policy.

"Of course there's a lot we don't know," McNeil said. "We don't go looking for these situations."

McNeil and the school's president, John McMahon, both declined to comment on Eledge's employment, citing a personnel confidentiality policy.

In 2012, Omaha passed an ordinance that that extended workplace anti-bias protections to gay and transgender workers. But the ordinance exempts religious organizations and schools, said Renee Biglow, human relations representative for Omaha's Human Rights and Relations Division.

Steven Willborn, a professor of employment discrimination law at the University of Nebraska College of Law, said Eledge is not protected by any local, state or federal law.

"If they had a rule against drinking, and they only enforced the rule against drinking for black teachers and not white teachers, they'd have a claim, because that's racial discrimination and illegal," Willborn said. "But here, their claim would be that they're treating him differently because of his sexual orientation, and there's just no law against that."

A bill in the Nebraska Legislature would extend discrimination protections to gay and transgendered workers, but it has a religious exception.

Any reversal would be more likely to come from a public opinion backlash, Willborn said, such as seen recently in Indiana when that state's lawmakers passed a religious objections law that critics said would sanction discrimination against gays and lesbians.

"Of course, the public opinion that would matter most at Skutt would be what their parents and supporters and donors think," Willborn said.

Asked if he's considering legal action, Eledge said he's only focused on teaching his students for the next six weeks. He has received a number of offers to teach at other schools next year, he said.

"So, maybe it's a blessing in disguise," he said. "I just want to teach."