The 369th Infantry Regiment, dubbed the “Harlem Hellfighters”, "proved the capabilities of African American troops, serving the longest of any American combat troops in the trenches," the National World War I Museum and Memorial says. (National WWI Museum and Memorial)

They were among the first Americans off the boats in France and were heroes on the battlefield during World War I, while also fulfilling crucial non-combat roles that helped lead the allies to victory.

When the African Americans who bravely fought overseas returned home though, they encountered only more of the ugly racism and discrimination they sought to eliminate, with 11 men in uniform among the 76 lynchings committed during the “Red Summer” of 1919.

It wasn’t until decades later that the Army would be desegregated, but now, in honor of Black History Month, the National World War I Museum and Memorial is raising awareness of the contributions of those during what they call the “turning point in the effort to make democracy safe for all Americans” – regardless of one’s skin color.

“The U.S. Army was very segregationist so they applied that at that time, but it did not stop the bravery both as individuals and the units who were fighting against the Germans,” Doran Cart, a senior curator at the Museum, told Fox News.

The Museum, in partnership with Google’s Cultural Institute, has been featuring an online exhibition entitled “Make Way for Democracy!” that delves into its archives to portray “the lives of African Americans during the war through a series of rare images, documents and objects.”

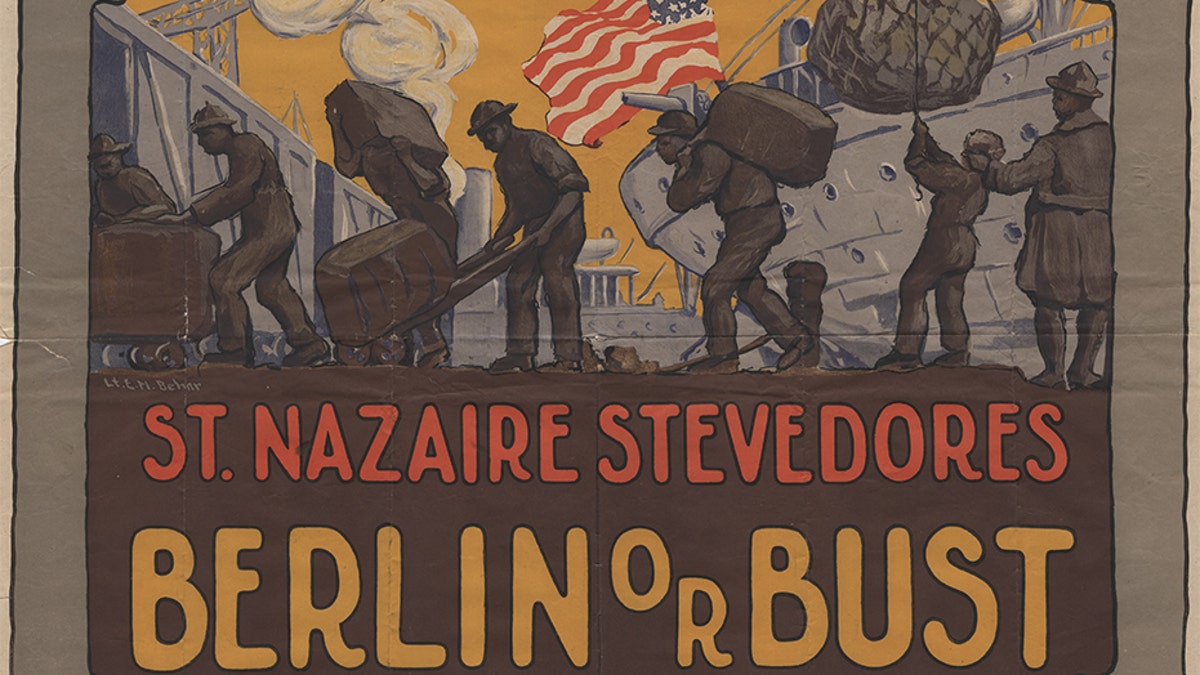

A poster promoting the work of stevedores, who helped transport and unload American cargo overseas to France during World War I. This role was one of many that African Americans filled during The Great War -- and an essential one that helped lead the allies to victory. (National World War I Museum and Memorial)

More than 367,000 African Americans were drafted into the U.S. Army during the war, making up around 13 percent of the armed services, the Museum says. Yet nearly 80 percent of them were placed into non-combat supply and construction roles and still suffered discrimination from civilians and their colleagues in the American Expeditionary Forces. African American soldiers in France were also falsely accused by white officers of being rapists.

However, despite the unjust treatment, the African American divisions and infantry regiments proved to be resilient in the trenches, particularly the 369th Infantry of the 93rd Division, under command of the French.

Given nicknames such as the “Harlem Hellfighters” the regiment spent a grueling 191 days in the trenches – the longest duration of any American combat troops during the war, the Museum says. The regiment was cited 11 times for acts of bravery and fought in some of the most important operations of the war, according to the National Guard.

WWII MUSEUM'S ONLINE BLACK HISTORY MONTH EVENT FEATURES 'UNHEARD' VOICES OF THE ERA

A color-bearer in the 93rd Division, which the Museum says was one of the 'most decorated American units of the war'. (National World War I Museum and Memorial)

One of its members, Sgt. Henry Johnson, became the first American to be awarded the prestigious French Croix de Guerre for bravery – and later went on in 2015 to posthumously be awarded the U.S. Medal of Honor.

"As night fell, U.S. Army Sgt. Henry Johnson found his observation post near Sainte-Menehould, France under siege by a dozen German soldiers," Fox News wrote in a story covering his recognition that year. "He fought them off until he ran out of ammunition, then used his rifle as a club, before taking on the rest hand-to-hand, with his bolo knife, eventually sending the enemy troops fleeing."

Another regiment of the 93rd Division, the 372nd Infantry, brought together African American troops from Connecticut to Tennessee, and were hailed for never surrendering or retreating during the war, the National Guard says. The regiment also captured around 600 prisoners, it added, during the deadliest battle in U.S. history – the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

The Museum, in the exhibition, says “a total of 68 Croix de Guerre and 24 Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to men of the 93rd Division along with several unit commendations, making it one of the most decorated American units of the war.

“The performance of the 369th and other African American combat units informed the American military to reconsider its segregation practices in later years,” it added.

And African Americans who didn’t see combat also were instrumental in defeating the Germans.

Red Cross nurses -- one of the roles African American women filled -- marching in New York City during World War I.

The exhibition says African-American women “found varied and successful ways to serve: nurses, ambulance drivers, Navy Yeomen, canteen workers, club administrators, office workers, railroad workers, munitions workers, and as extremely successful fund-raisers with a variety of government organizations and departments, relief organizations, and war industries.”

AMERICA'S DEADLIEST BATTLE: WORLD WAR I'S MEUSE-ARGONNE OFFENSIVE, 100 YEARS LATER

In person, the Museum, which is based in Kansas City, Missouri, is showcasing uniforms, patches and other items African American troops carried or wore while in France.

The online exhibition also features past audio interviews with William T. Knox, a soldier with the 366th Ambulance Company, 92nd Division, who talks about “wild” celebrations with champagne flowing in France on Armistice Day, and Robert L. Sweeney, a supply clerk with the same division.

“When the French people welcomed us with open arms, that is the only time that I ever realized what a real American soldier was,” Sweeney said. “The French people had no prejudice whatever.”

Lieut. Col. Otis Duncan, right, of the 370th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Division, was the highest ranking African American in the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

But when he was discharged, Sweeney said the “American white man did everything to play you down and degrade you and not let you think you had been over there to fight to make the world safe for democracy.

“They wanted to put you in your place,” he said. “That came from Washington all the way down. In other words, he's always tried to make me think that I have a certain place. That never bothered me, because I never let it bother me.”

Cart says in the summer of 1919 after the war ended, there were “countless lynchings of men of color in uniform” and more than 30 race riots took place across the nation.

“The summer of 1919 when the majority of American troops returned to the U.S. was a horrible summer for African American men in uniform,” he told Fox News.

Yet later on, the Museum says, “military research would conclude that ‘shared combat experiences can change racial attitudes.’

A uniform of the 369th Infantry Regiment, currently on display at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri.

“African American involvement in this war did not end racial subjugation or segregation,” the exhibition concludes, noting that the “act of putting a uniform on itself was, for some, an act of defiance, and for others, an act of unity and equality.

“That participation marked the beginning of a modern civil rights movement, a fight to define the true meaning of democracy.”