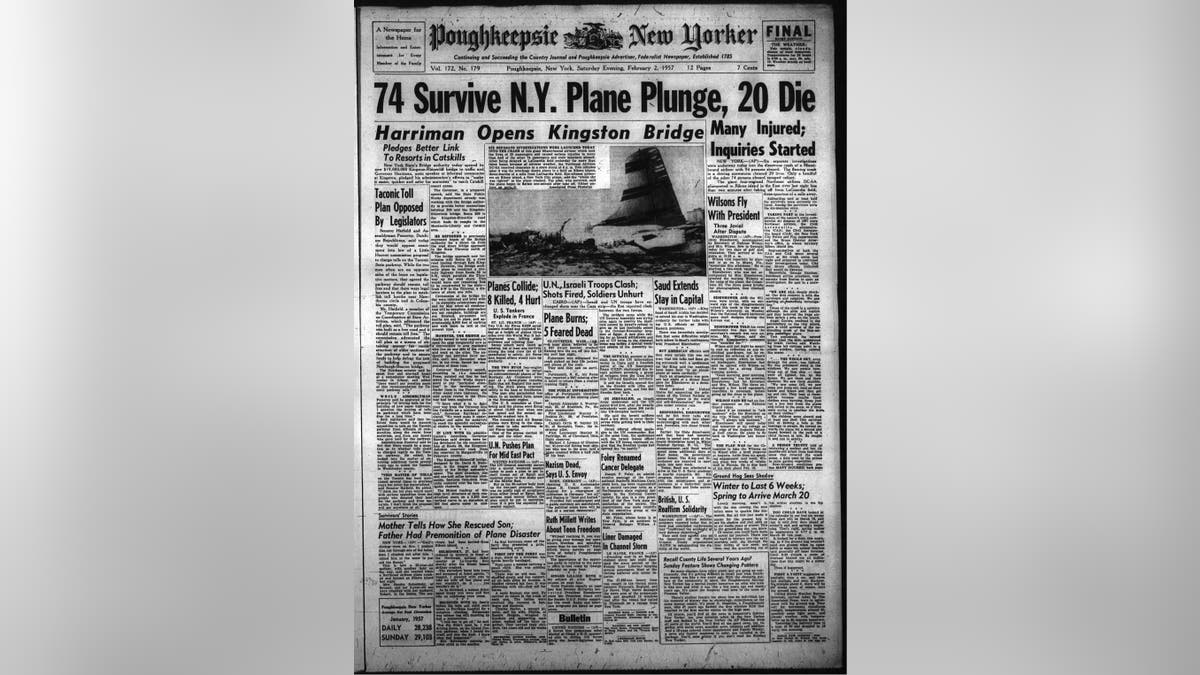

The Poughkeepsie New Yorker reported on the crash of Northeastern Airlines Flight 823 in its Feb. 2, 1957 editions. (Newspapers.com)

On Feb. 1, 1957, Miami-bound Northeast Airlines Flight 823 took off from New York’s La Guardia Airport in near-blizzard conditions. Less than a minute later, its twisted wreckage lay engulfed in flames in a jail yard in a wreck that killed 20 and remains one of the most enigmatic crashes in aviation history.

In retrospect, the flight seemed doomed from the beginning: Its pilot had already been involved in two prior crashes, takeoff was delayed more than three hours and the weather was fierce. But what followed, after the plane dived into the grounds of the Rikers Island jail, added to the grim mystique that still surrounds the incident to this day.

“It was my first flight and my last flight; I never flew again,” Phyllis Naylor, 91, a crash survivor, told Fox News from her home in Langhorne, Pa. “My husband Charles had heard that the back of the plane was safer, so that’s where we were.”

Flight 823, a Douglas DC-6A, was scheduled to leave La Guardia at 2:45 p.m. but wasn’t clear for takeoff until 6:01 p.m. Crash investigators would later determine it reached an altitude of just 200 feet before going down.

CLICK TO SEE PHOTOS OF THE FLIGHT 823 CRASH

The takeoff seemed fine, Naylor noted. "But then I saw this 'oh-my-God look' on my husband's face; in an instant, the plane listed, the left wing was cut off and our side of the plane was tipped up real high."

Seconds later, the plane was on the ground. As survivors among the flight’s 101 passengers and crew stumbled from the wreckage and into the snow, their flesh burning and their cries piercing the evening air, Rikers Assistant Deputy Warden James Harrison made the unprecedented decision to release prisoners to aid in the rescue. It may have saved lives: The city’s own first-responders were delayed getting to the scene by bad weather and a remote location.

Naylor and her husband, who were going to Miami to celebrate his new gig as piano soloist in the Fred Waring Band, managed to get out of the plane, and jumped into a pile of snow. Naylor remembers that Charles and another passenger rolled her around in the snow and hers and Charles' hands and face were dripping. "We realized eventually that it was our burning skin sliding off."

"The night was silent, except for the screams," Naylor said.

Phyllis and Charles Naylor were taken to the prison chapel, and by the time they were transferred to Albert Einstein Hospital, "my hands looked like toasted marshmallows," Naylor said. "It was the worst pain of my life."

Angel Gorbea, who witnessed the crash from his cell at Rikers Island before racing to the scene, told The Associated Press at the time: “The whole sky, even through the snow, was lighted. We, the prisoners, stood at the windows. We saw people tumbling out of that ship -- they were all lighted, too, by the flames. We saw them and their shadows.”

Tugboats maneuvered to the scene, slogging through the East River to reach the victims.

“When we got there, people were falling out of the wings of the plane and the fuselage,” tugboat Capt. Earl Jensen told WNYC reporter Monroe Benton.

The Naylors spent two months in the hospital, and Charles' hands were so damaged that he was unable to resume his career as a pianist. Charles, who died in 1994, put his energy into composing music, unable to stretch his hands in the way required to perform classical pieces. Phyllis was a high school English and drama teacher.

The pilot, Capt. Alva Marsh, later told investigators he believed the plane struck a pole, causing it to dip sharply left and sending it downward. Upon impact, the plane’s left wing was sheared off and its outboard engine ripped from its mounting as it burst into flames.

An aerial view of the Rikers Island Prison Complex, which sits on the East River between the Bronx and Queens, in New York City.

Marsh had been in the cockpit during crashes in 1952 and 1953. In each of those accidents, no one died. This time, the dead included a child.

Inside the jail, Harrison gave the order to release more than 50 inmates known as “trusties” -- prisoners whose good behavior had earned the guards’ trust. They raced to the scene to help stunned passengers and crew. Every single inmate returned to their cell later that night.

One stewardess who worked the flight, Doris Ostermann, suffered catastrophic injuries shepherding passengers to safety.

"She was terribly deformed; her nose and ears were burned away," Paula Aubee, Ostermann’s niece, told Fox News.

"It was shocking as a child to see those physical traits," recalled Aubee, who was 8 at the time of the crash. "But my aunt was always fun-loving. She never lost that."

Ostermann, who was Doris Steele at the time of the crash, had aided in two historic airlifts during the 1940s: She led Jewish refugees from China to Israel and participated in the Berlin Airlift.

"She loved every minute of being a stewardess and was outrageously in love with flying," Aubee said. As Ostermann healed, Aubee remembered how her aunt said she couldn't wait to get back on a plane, although her injuries kept her from a career as a stewardess. "She couldn't pick things up."

"She was an adventurer. She was this fairy godmother to us," said Linda Nilsson, another niece of Ostermann, "bringing us things from all around the world."

Ostermann died in 2010 of a stroke at the age of 87.

For their part in the rescue, 30 of the 57 inmates who ran to help were released and another 16 had their sentences reduced by the New York City Parole Board. Mayor Robert Wagner bestowed on Harrison the Correction Department’s highest award: the Medal of Honor.

The Civil Aeronautics Board investigators determined that Marsh’s inability to properly interpret the plane’s flight instruments was the probable cause of the crash. Marsh never again flew an airliner. He was reassigned to a desk job at Northeast Airlines. He died in Florida in 1985 at the age of 78.

CLICK TO READ THE CIVIL AERONAUTICS BOARD REPORT

The crash shows that "life is uncertain and men are frail and make mistakes," Alvin Moscow, who wrote about the Flight 823 crash in his book "Tiger on a Leash," told Fox News. "This is one crash where everything that could go wrong with a plane did go wrong."

For Phyllis Naylor, the crash was, in some odd way, "a blessing."

"You remember the kindness -- of an African-American inmate who gave me a cloth to wrap my hands, of the doctor who treated my burns. Truth is, we had a wonderful life; it has made me appreciate everything."