Pennsylvania city feels painful effects of opioid crisis

Fox News' Rick Leventhal looks at how drug use has taken its toll in Reading, Pennsylvania.

The flight of industry has decimated a small Pennsylvania town, and the inundation of opioids has its back against the wall – and some of the city’s men are paying the price.

Reading, Pa., is a town plagued by declining education rates, rising drug-related deaths and a population mired in poverty. For many of its men, there is no opportunity or respite.

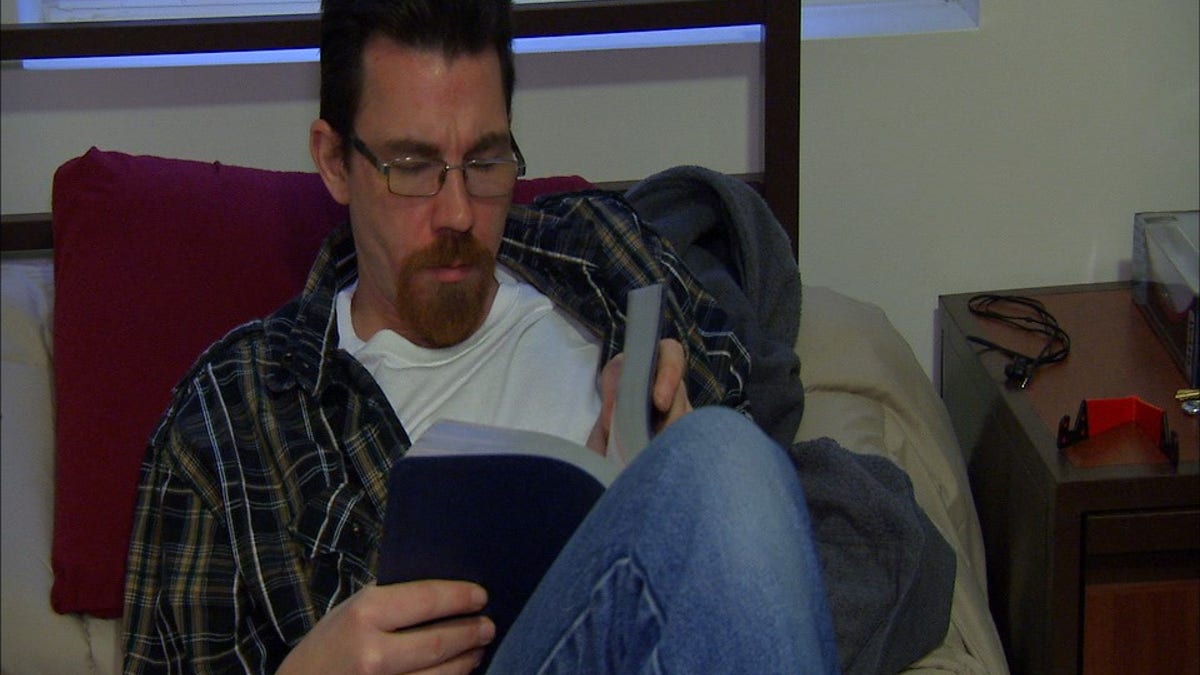

T.C. Wilson knows this struggle all too well. He’s a resident at Hope Rescue Mission, a homeless shelter in the city. The 34-year-old is a lifetime resident of Reading and said it has experienced a steady decline in quality of life alongside upticks in violence and drug use.

"You know, I got involved with heroin and lost my job, which I worked for ten years straight. I was in line to be a foreman. … I just didn’t care, I stopped caring about everything."

“They’ve gotten worse,” Wilson said. “You can’t walk five blocks without walking into a drug dealer or an abandoned house that people break into to get high.”

Wilson, like two-thirds of the city’s adult residents, only has a high school diploma. That’s a striking difference from the national 85 percent of young graduate. Only 8 percent of residents have a bachelor’s degree, a stark gap from the 28 percent who have them nationwide.

This gap in educational attainment leads many residents down a path of little prosperity – nearly 40 percent of people in Reading live in poverty, according to figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Wilson graduated high school, but not without his share of struggles. At 15 years old, he said he was kicked out of his home by his mother over money disputes.

“She had a lot of money issues,” he said. “And I was paying rent at the time at the jobs that I was working. … And money wasn’t going towards what I was giving her to go towards, and so I stopped giving her money.”

This sense of apathy pervades many in the state, where suicide is the second leading cause of death for people aged 25 to 32. On average, one person dies every five hours on average in Pennsylvania.

Despite the hand he was dealt, Wilson persevered. He graduated in 2002 after working a series of jobs at Walmart, a nursing home and as a paperboy. Nearly a decade later in 2011, Wilson was engaged to a woman when he returned home to find her dead from a brain aneurysm on the bathroom floor.

“When I came home from work, you know, I had to find her the way she was,” he said. “And, to be honest, it kind of destroyed me. It still hurts.”

Her death sent him into a spiral of drug abuse and poor decisions. Wilson escaped his addiction with his life, a stroke of luck many in Reading don’t receive. In 2016, more than 4,500 died from drug-related overdoses, an increase of 37 percent from the year prior, according to a Drug Enforcement Agency analysis.

T.C. Wilson is a lifetime resident of Reading and said it has experienced a steady decline in quality of life alongside upticks in violence and drug use. (Fox News)

More than 13 people died daily from overdoses, the vast majority from opioids.

“That took me straight to jail after a few years,” Wilson said. “You know, I got involved with heroin and lost my job, which I worked for ten years straight. I was in line to be a foreman. … I just didn’t care, I stopped caring about everything.”

This sense of apathy pervades many in the state, where suicide is the second leading cause of death for people aged 25 to 32. On average, one person dies every five hours on average in Pennsylvania, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Wilson would eventually find love again and got engaged to a woman named Megan. They had a daughter together, who was six months old when they were both put in jail.

“I came home from work, and she was dead in the bathroom. She relapsed while I was at work, and my 3-year-old daughter was home alone with her for two hours."

He found himself at rock bottom when his daughter was put into the system while he served eight months in jail. He went to rehab and a sober-living facility near Philadelphia; throughout it all, Wilson vowed to get his daughter back.

Eventually, after he said he jumped through every hoop the court set before him, he was granted full parental rights. Wilson said it was important his daughter raised by her parents, a privilege he was never given.

“I didn’t even know who my father was,” Wilson said. “I’m named after someone who isn’t my father. … I didn’t want my daughter not to know who her father was.”

Wilson was actively working on getting himself set up for success, even planning on buying his grandmother’s house after she passed away. Things were going well with his fiancée; then the unthinkable happened again.

Wilson says he hopes to be a full-time father to his daughter soon. (Fox News)

“I came home from work, and she was dead in the bathroom,” he said. “She relapsed while I was at work, and my 3-year-old daughter was home alone with her for two hours. I don’t even know how to explain that feeling, once is hard enough.”

The hits kept coming after his fiance’s death; Wilson’s car stopped working, and he promptly lost the job he obtained through a temp agency. He was left with no choice but to ask his sister to take his daughter while he checked himself into Hope Rescue Mission, a local homeless shelter.

“A lot of the times we’re dealing with folks that are in addiction, folks that have grown up in households where, you know, function behavior might not have been modeled,” Frank Grill, director of Hope Rescue Mission, said. “So you’re trying to kind of change those heart sets and mindsets of the individuals that come through here.”

"I can’t even put into words, like, between the guidance that the staff has given me, the trust they give me, the opportunities that they’ve given me – it’s overwhelming sometimes"

The faith-based organization serves two primary roles: a place for destitute men to stay for overnight shelter, and a long-term home for those who want to join their “discipleship” program to secure jobs and eventually have a place of their own. Wilson is eight months into the latter.

A leader at the shelter, Wilson works two jobs in addition to security detail. He said he hopes to be stable and find a home to move into soon. Most importantly, he hopes to be a full-time father to his daughter soon. Hope Rescue Mission has proved a buoy to men like Wilson who are flailing in life’s waters.

“I can’t even put into words, like, between the guidance that the staff has given me, the trust they give me, the opportunities that they’ve given me – it’s overwhelming sometimes,” he said. “Because climbing up those 19 steps, you feel broken.”