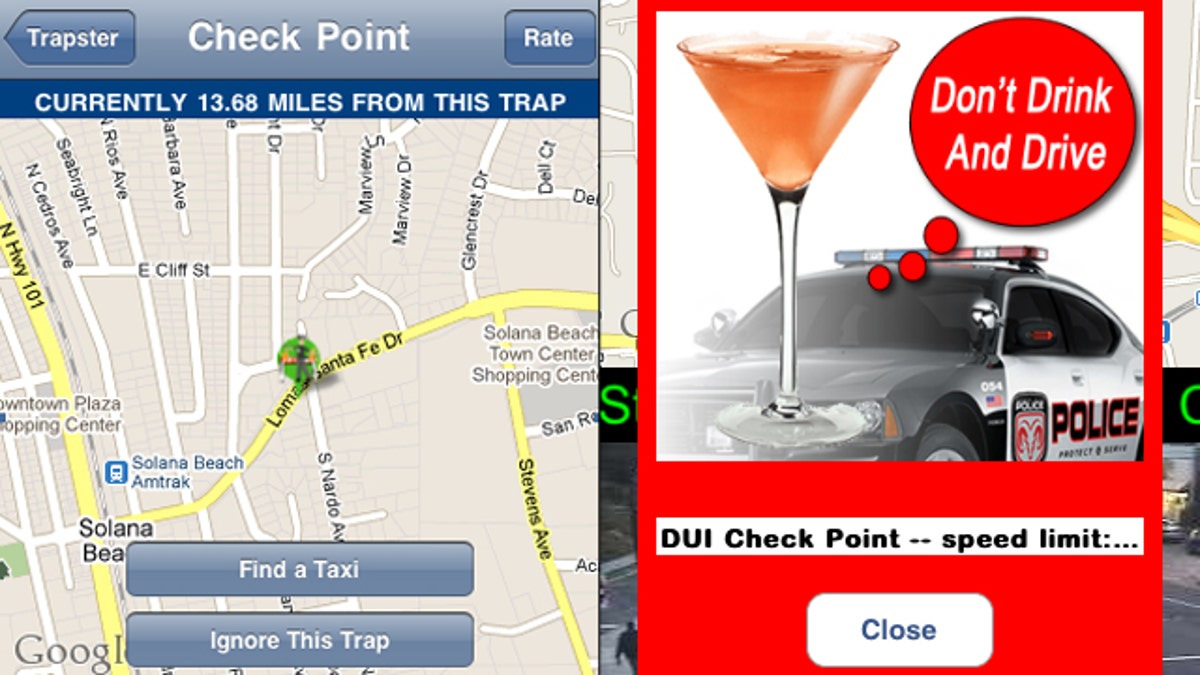

Shown here are screens showing the Trapster application, left, and PhantomALERT, right. (Trapster/PhantomALERT)

Want to drive drunk? There's an app for that -- a fact that has consumers concerned and politicians nationwide calling for a ban and asking questions.

If it's acceptable to get warnings about speed traps and red light cameras, for example, is it also acceptable to get warnings about police sobriety checkpoints? When does a new technology's dangers outweigh its benefits?

On the Apple App Store at present is Buzzed for 99 cents, Checkpointer for $4.99, and Tipsy, a free app. The Android Market has Checkpoint Wingman for $1.99 and Mr. DUI, a free program. That may be changing: Last week smartphone developer Research In Motion -- which makes the Blackberry handsets -- decided to pull the plug on at least one application, PhantomAlert.

The impetus for the move was a letter from four U.S. senators asking the company to remove any apps that identify the location of police DUI checkpoints. The letter was also sent to Google and Apple too, which offer similar apps for their smartphones.

A spokesman for Google said the offending apps did not appear to violate the law or the company's own rules for software developers. Apple did not return requests for comment, but when I last checked, several apps were still available on the iTunes store. And so far the programs are still available for Android phones.

According to transportation statistics, roughly 10,000 people are killed on America's roadways because of drunk driving each year. That's an astonishing statistic considering the airbags, side-curtain airbags, improved seat belts and more now in vehicles. So its not surprising that the senators complained these apps put "innocent families and children at risk."

Apps like this aren't new, of course.

PhantomAlert unveiled a DUI checkpoint feature in the fall of 2009; it now contains a database of 500,000 locations. Some demarcate permanent radar or red-light cameras at dangerous intersections across the county. Other points of interest are submitted by drivers and mark temporary radar traps and DUI checkpoints in real time. Those spots are confirmed by other drivers, and then warnings appear on the screens of PhantomAlert users traveling in the area.

The idea of warning people about sobriety checkpoints seems like a bad thing, lulling drivers into thinking they can skirt the law even after they've had a few too many. But the software creators have an important point to make: The apps help law enforcement by acting as a deterrent.

"Basically, they think twice before they drink and drive," said Joe Scott, PhantomAlert's founder. He argues that some municipal police departments publicize DUI checkpoints for the same reason: to remind people to not drink and drive.

An analogous debate has arisen over red-light-camera detectors, which use a database of camera locations and correlate it with your GPS location. As you approach an intersection that has a camera, the detector beeps at you and issues a warning: "Photo enforcement!"

This can help you avoid a ticket -- and make you aware that you are approaching a dangerous intersection requiring extra care. (I've found that I pay more attention after the alert goes off.)

This is why some cities post signs warning drivers that there are cameras at certain intersections: Attempting to hide them defeats the safety objective of preventing accidents. Yet the New York City department of transportation suggested to me that the use of red-light-camera detectors would encourage people to break the law.

Of course, this makes no sense at all.

Barring the obvious exceptions (bank robbers and car thieves), no one wants to run a red light. When it happens, it's not intentional; it's due to inattentiveness. (The same cannot be said of speeding; when the road is clear, many of us want to get to our destination more quickly.)

So does the same argument apply to DUI checkpoint alerts? Probably not.

Publicizing sobriety checkpoint weekends, for example, can boost awareness among the driving public and make people think about designating a sober driver or planning to pay for a cab. However, it probably doesn't change the behavior of people who have an addiction to alcohol and who have been repeat DUI offenders. Indeed, for those people, a program that warns them about imminent police checks may help them avoid apprehension.

So what should we do about it? It is not illegal to use these programs, after all. But pressure to remove them may be building.

On Monday, Maryland attorney general Douglas F. Gansler and Delaware attorney general Beau Biden joined the senators and called on Apple and Google to ban DUI checkpoint alert apps. Meanwhile, proponents of the software wondered what could be next -- censoring Twitter messages about checkpoints? Banning Facebook groups that alert friends about DUI crackdowns?

What will happen to this new technology remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: No one wants drunk drivers on the road.

Follow John R. Quain on Twitter @jqontech or find more tech coverage at J-Q.com.