Fox News Flash top headlines for March 18

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

Have you ever gotten a whiff of a certain smell that brought you back to childhood? Or maybe a scent that reminded you of a past love affair?

A paper published in Learning and Memory reveals the power scents have to trigger memories of past experiences, as well as the possibility for odor to be used in treating memory-related disorders.

"If odor could be used to elicit the rich recollection of a memory -- even of a traumatic experience -- we could take advantage of that [therapeutically]," said Boston University neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, assistant professor of psychology and brain sciences and senior author of the study, in a statement.

The traditional belief about how we retain memories goes like this: Systems consolidation theory suggests that our memories start out being processed by a small part of the brain called the hippocampus, which gives them rich details. Over time, the set of brain cells that holds onto a particular memory reactivates and reorganizes. The memory is later processed by the prefrontal cortex, and details sometimes get lost.

VERNAL EQUINOX BRINGS EARLIEST SPRING TO US IN 124 YEARS

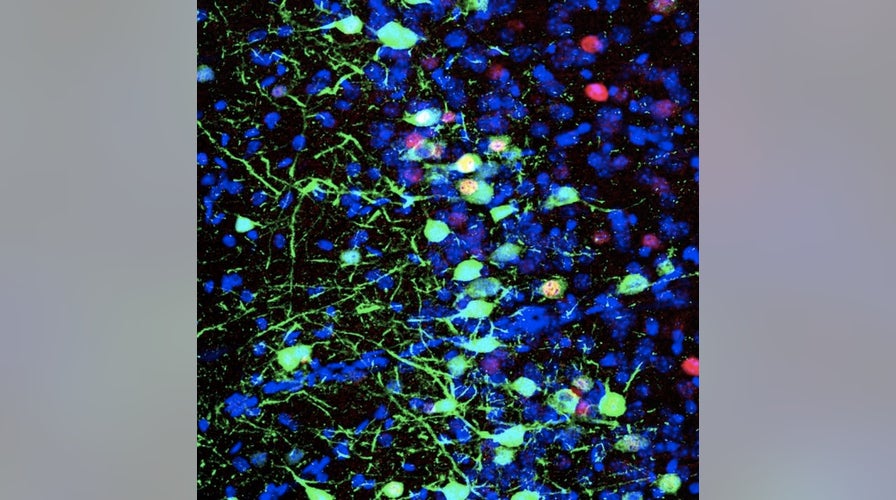

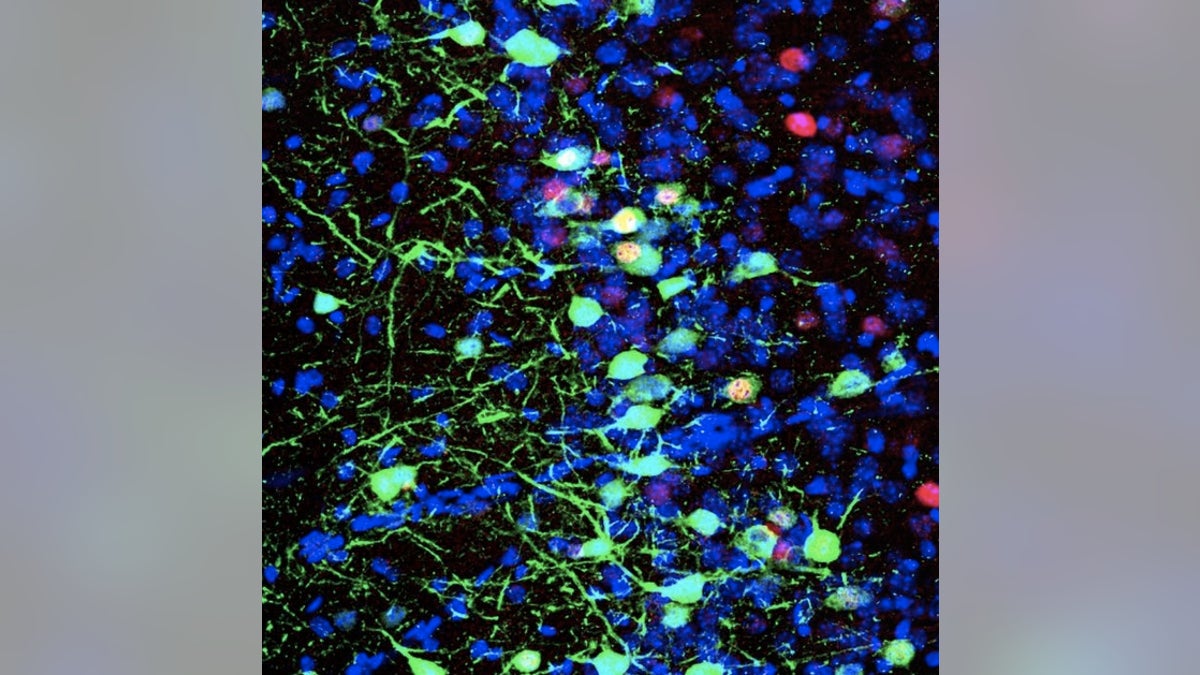

Pyramidal cells in the mouse prelimbic cortex (shown in blue) that were active during the formation of a discrete memory (shown in green). (Dr. Stephanie Grella (Ramirez Lab))

AIR POLLUTION INCREASES CORONAVIRUS VULNERABILITY, EXPERTS SAY

In order to answer the question about why scents, which are processed in the hippocampus, can trigger seemingly dormant memories, the academic researchers at Boston University's Center for Systems Neuroscience created fear memories in mice by giving them a series of harmless but startling electric shocks inside a container.

Half of the mice were exposed to the scent of almond extract during the shocks, while the other half were not exposed to any scent.

Twenty days later, researchers found that in the no-odor group, processing of the fear memory moved to the prefrontal cortex. However, the odor group still had significant brain activity in the hippocampus.

"[This finding suggests] that we can bias the hippocampus to come back online at a timepoint when we wouldn't expect it to be online anymore because the memory is too old," Ramirez says. "Odor can act as a cue to reinvigorate or reenergize that memory with detail."