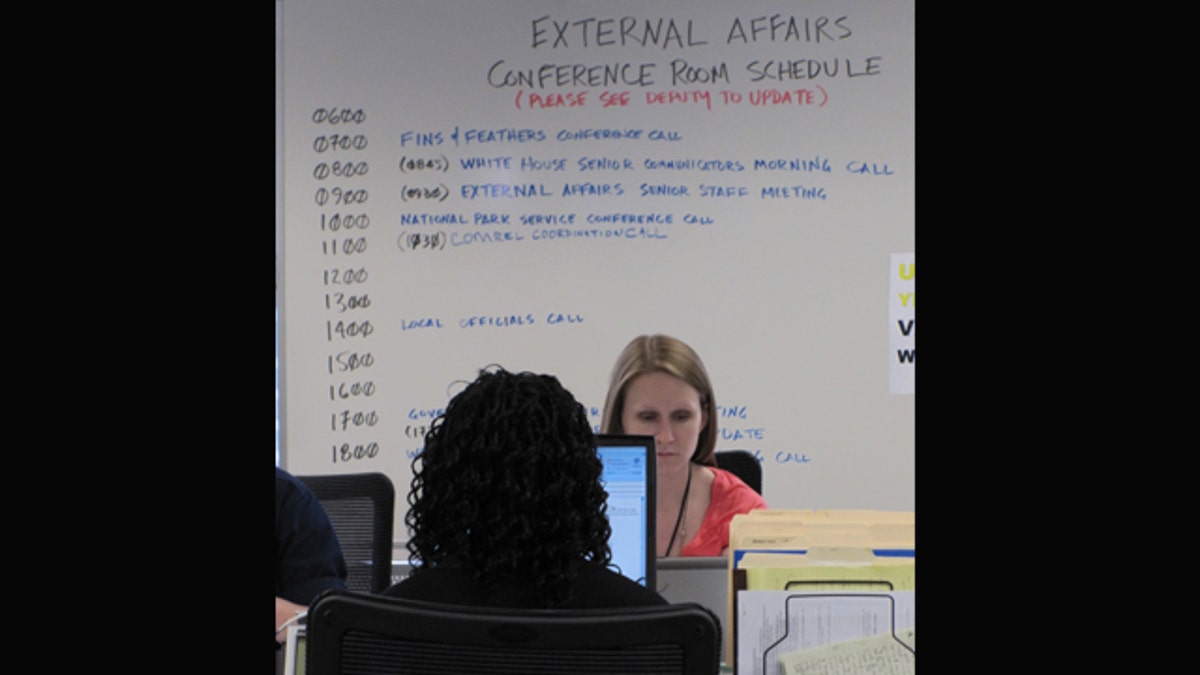

June 2010: U.S. Coast Guard's BP oil spill Unified Area Command Center in New Orleans. (FNC)

WASHINGTON -- The Obama administration failed to set up an "effective" communications system during last year's BP oil spill and threatened its own credibility by "severely restricting" the release of "timely, accurate information," according to a newly released report commissioned by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Quietly posted on the Coast Guard's website two weeks ago, the report offers the first major assessment of the federal government's communications efforts during the worst oil spill in U.S. history.

"Several layers of review and approval by the White House and (Department of Homeland Security) prevented timely and effective crisis communications and hindered the Coast Guard's ability to ... (keep) stakeholders informed about the status of the response," the report reads, adding that "accurate and timely messaging from the response organization improves transparency with the public."

Information centers in Houma, La., and Mobile, Ala. -- established by the Coast Guard in accordance with pre-set plans for major disasters -- were "effectively muted," the report reads.

Photographs could not be released without Washington's blessing, and Coast Guard officials leading efforts on the ground "were not authorized to conduct media interviews, hold press conferences or send press releases without prior approval from DHS," according to the report.

Asked about the report, sources with knowledge of White House and DHS involvement went even further, saying the administration "looked at this as a political problem, not an operational problem." After all, one source said, the 2010 midterm elections were drawing closer as the oil spill crisis deepened, and the White House "went into campaign mode."

An administration official, however, strongly disputed that contention, saying involvement from the White House and DHS in Washington was "a necessary step" after what began as a relatively routine Coast Guard response became a "unique and unprecedented" government-wide effort. More than 40,000 people took part in the response.

"Calls were coming in -- both in Washington and in the Gulf region -- and it was imperative given all the moving pieces that information remain consistent," the official said. "Throughout the course of the spill, we executed a successful effort to consolidate the release of information among 17 federal agencies."

The official noted that DHS appointed outgoing Coast Guard Commandant Thad Allen to be the National Incident Commander, effectively the government's "principal spokesman." The report described Allen as a "credible spokesman" who "proved to be an effective means of communicating a unified message to the public."

In addition, the official said, the administration engaged in a "robust" effort to keep the public informed, including daily briefings by Allen and daily "fact sheets" issued to the press and posted online.

At the same time, the report reads that the Coast Guard lacked "enough senior personnel with the requisite crisis communications training and/or experience to effectively manage the public affairs campaign for an incident of this magnitude," and those who had the requisite training or experience "were quickly overwhelmed by the tremendous demand for information."

Early on, senior Coast Guard officials made public missteps. In the days after the explosion ripped through the Deepwater Horizon in April 2010, Rear Adm. Mary Landry, then the head of the response effort in the Gulf region, told reporters, "We do not see a major spill emanating from this incident."

In a statement to Fox News, a Coast Guard spokesman said the newly released report "does not reflect the views of the Coast Guard," but one of the sources with knowledge of White House involvement said it "depends on who you talk to." Essentially, the source said, the oil spill response created "a clash of cultures," with operational needs scraping against political ones.

Nevertheless, the report states the communications system put in place was a departure from prior practice, with White House and DHS officials in Washington becoming gatekeepers to information about developments in the Gulf Coast.

"If any level of the response organization is restricted from interacting with the media and the public in any way, it has the potential to damage the credibility of the Federal Government and erode public trust," the report reads.

Information about the incident was "channeled up" to the Unified Area Command, the regional hub of the response effort, where it "was packaged and released after review and approval" from the DHS public affairs office in Washington, the report reads. At the time, some of the most senior Coast Guard officials expressed frustration with the process, a source said.

"The additional handling and approval process for releases of information often prevented the response organization from providing real-time information," according to the report. "Because the Coast Guard was severely restricted in its ability to distribute timely, accurate information, it was perceived by some that the Federal Government was purposely withholding information pertaining to the incident from the American public."

The administration official, however, insisted such a process is routine in federal government, saying agencies "do run things up the chain, and they come back down" every day. In addition, the source who said the White House "looked at this as a political problem, not an operational problem" noted the Bush administration looked through a similar prism and likewise took control of the message during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

"Negative press equals lost votes," the source said. "It's not a political party thing, it's about political operatives and what's in their comfort zone."

The newly released report offers no specific cases of delayed or restricted information, and one source said he was not aware of any substantive information or photograph ultimately prevented from being released. But, the source said, it would take up to eight hours for DHS or the White House to approve a photograph's release. Another source involved with the oil spill response said he knew of at least one press release that was not immediately sent out due to fears it could upset environmental activists.

In one instance, a Coast Guard official was directed to release information that -- unbeknownst to him -- was at best misleading, according to two sources. The information related to whether the White House was controlling the oil spill message.

In May 2010, amid media concerns that access to impacted areas was being restricted, a Coast Guard public affairs official told The Associated Press that the White House had to sign off on all requests for tours of the spill zone. In response, the White House referred questions to Coast Guard Lt. Commander Rob Wyman who told The Associated Press that the official's description of the process was incorrect and that all requests from media were "decided on by the command center in Robert, La."

Those assertions contradict the findings of the newly released report, and administration officials did not deny that the official's initial assessment was correct after all. An e-mail to Wyman Sunday seeking comment was not returned.

The administration official, meanwhile, dismissed the report, which offers no direct attribution for its statements, as little more than "an opinion piece." Only six pages of the 167 pages address the issue of "external communications," with the rest of the report analyzing other aspects of the response like other recent reports have.

"Compared to the meticulously researched and sourced Oil Spill Commission Report (released Wednesday), this one is sufficiently lacking in both and, as such, is being received accordingly," the official said.

The official said the report "is just one of many reports that have and will continue to inform the Coast Guard's efforts to prepare for and respond to a catastrophic oil spill."

The report, officially dubbed an "Incident Specific Preparedness Review," was authored by an 11-member team of representatives from inside and outside government. Nearly 100 people were interviewed by the team, more than a third of them current or former Coast Guard officials. Four DHS officials and two White House officials were interviewed. The report was finalized in January.

Perhaps ironically, some within the Coast Guard wanted to issue a press release two weeks ago announcing the report's release, but those efforts were quashed.