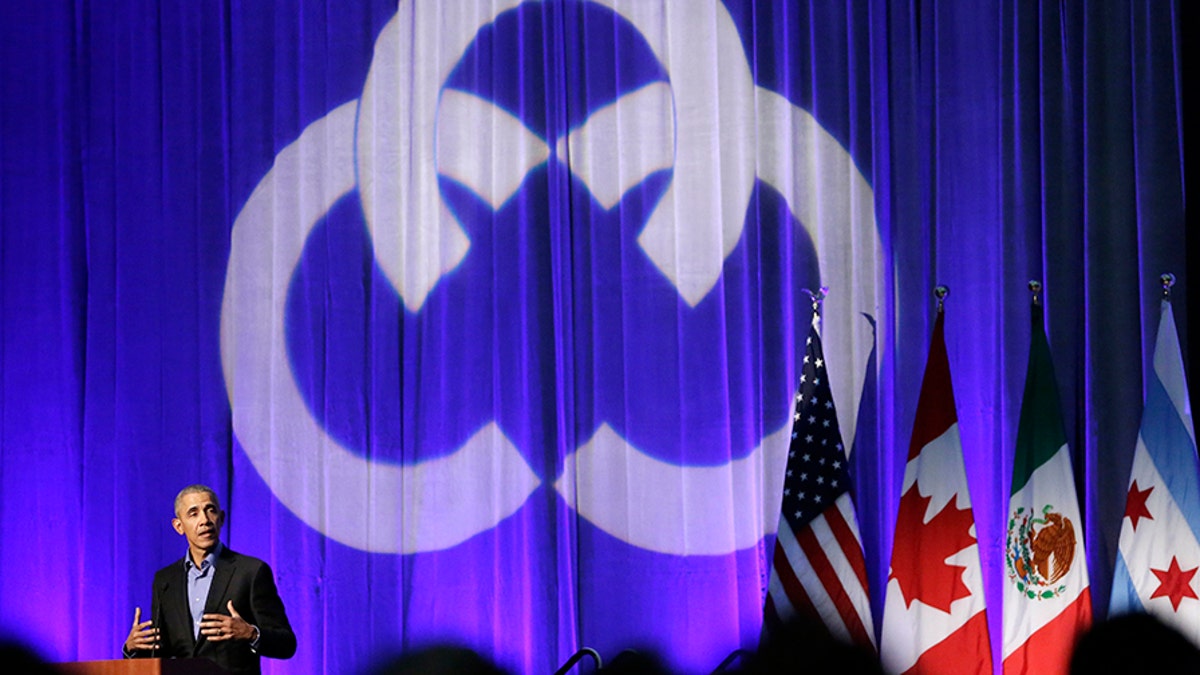

Former President Barack Obama address the participants at a summit on climate change involving mayors from around the globe Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2017, in Chicago. The conference comes after President Trump said the U.S. will pull out of the Paris agreement. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast) (Copyright 2017 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

Backers of the United Nations-sponsored Paris climate agreement are switching strategies after the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the deal, by dramatically stirring up grassroots forces.

Their aim: to keep greenhouse gases declining drastically despite the Trump setback by whipping up state and local promises to “roll back the forces of carbonization,” culminating in a Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco next September -- just before the U.S. off-year federal elections.

Business and social leaders also will be urged to join in, along with “scientists, students, nonprofits—anyone who recognizes that climate change is an existential threat to humanity,” according to the Climate Summit’s website exhortations.

In other words, the climate movement is in the throes of acknowledging that it needs to renew its own energy—or, as the Summit website puts it, “underscore the urgency of the threat and channel the energy and idealism of people everywhere to overcome it,” just as top heavy U.N.-sponsored climate summits have tried to do several times in the past.

The host of the San Francisco event, California Gov. Jerry Brown, has already vowed to regulate greenhouse gas emissions in California down to 1990 levels by 2020. His chief cohorts are former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, since 2014 the U.N.’s Special Envoy in charge of mobilizing cities around the climate change issue, and Patricia Espinosa, executive secretary of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the U.N. body sponsoring the Paris treaty.

Former President Barack Obama, left, shares a laugh with Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel after Emanuel introduced Obama at a summit on climate change involving mayors from around the globe on Dec. 5, 2017, in Chicago. (AP)

Quietly acting as “administrative fiduciary” for the event is the United Nations Foundation originally created by Ted Turner, which will “support the Summit’s fundraising, partnership and communications needs,” the Foundation told Fox News, and is already adding staff for the event.

“More than just an event, the Summit will catalyze climate action through 2020 and beyond,” the Foundation promises in one of its Help Wanted advertisements.

The catalyzing, in fact, is already starting this week, with a first-ever North American Climate Summit in Chicago of mayors from the U.S., Canada and Mexico—including nearly 400 U.S. mayors who have committed to the goals of the Paris Agreement, and who hope to encourage still more to join in.

One of the keynote speakers on December 5 was former President Barack Obama, who hailed U.S. cities and states as the “new face of American leadership” on climate change. Obama set the U.S. target for the Paris accord of a 26 to 28 percent reduction in U.S. greenhouse gases by 2025, and unleashed a dramatic array of regulatory policies to try to make that happen.

Former President Barack Obama hailed US cities and states as the “new face of American leadership” on climate change.

Some of the most draconian of those measures, like the EPA-sponsored Clean Power Plan, are under review by the Trump administration and are certain to be scaled back.

As a countermeasure, mayors at the Chicago meeting were invited to sign a Chicago Climate Charter, committing them to “addressing climate change at the local level,” and declaring that the gathered mayors’ reductions will happen “regardless of action taken by their respective federal governments.”

Just how the promises made in Chicago will be enforced, or even monitored, and the cumulative impact they will have, is still fairly unclear.

Nonetheless, the North American local politicians will be cheered on by a Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate And Energy, which says it is an “international alliance of cities and local governments” of all shapes and sizes—a heavy concentration are in Europe-- with a “shared long-term vision of promoting and supporting voluntary action to combat climate change and move to a low emission, resilient society.”

U.N. Special Envoy Bloomberg, as it happens, is also one of the co-chairs of the Global Covenant Board. The vice chair is Christiana Figueres, who was the UNFCCC executive director before Espinosa, from 2010 to 2016.

The top leadership of the grassroots movement, in other words, is something of a closed circle.

More than anything else, the Chicago and San Francisco events, as well as others that doubtless will occur in 2018, are intended as much to rebuild flagging enthusiasm for climate change goals as to cause significant impact on the world’s carbon emissions.

The problem for the Paris supporters is not merely the Trump Administration, but more the fact that the goals themselves currently appear far out of reach. .

According to the most recent annual global greenhouse gas emissions report by the U.N. Environmental Program, issued last November, government pledges “cover no more than a third of the emissions reductions needed” under the Paris agreement.

This, the report says, is “creating a dangerous gap, which even growing momentum from non-state actors cannot close.”

And beyond that, the report says, “more ambitious” state commitments “will be necessary by 2020.” According to the assessment, “between 80 and 90 percent of coal reserves worldwide will need to remain in the ground, if climate targets are to be reached. This compares with approximately 35 percent for oil reserves and 50 percent for gas reserves.”

Whether that would ever happen is a question that goes far beyond the U.S. and the Trump administration.

In Germany, Angela Merkel’s anti-fossil fuel and anti-nuclear policies have become almost as unpopular in many circles as her controversial immigration policies were. In Japan, anti-nuclear policies are leading to a major planned hike in coal-fired electrical plans.

Canada, Mexico, South Africa and the European Union, as well as the now-dissenting U.S. were all deemed in the UNEP emissions report as “likely to require further action” to meet their further carbon reduction targets for 2030.

Moreover, the report adds, “it is currently unclear how many of the actions by non-state actors” are already included in those unsatisfactory national pledges.