Obamacare: Co-ops, premiums worry consumers

After leaving office, President Obama, admitted that Obamacare ‘was not perfect.’ Here is a look at some of the problems facing the Affordable Care Act

As Senate Republicans try to revise and resuscitate their alternative to the Affordable Care Act, issues with the current law of the land are only getting worse as co-ops crash, insurers pull out of individual markets and premiums spike to double-digit highs.

Democrats have decried the plan to repeal and replace ObamaCare and instead have pushed to patch up problems with the malfunctioning model. Even the law’s namesake, former President Barack Obama, has admitted the ACA could use some tweaking.

In a recent Facebook post, Obama said the law wasn’t perfect but “represented a significant step forward for America.” President Trump has called it a “disaster” and claims every other nation in the world has a better system in place.

OBAMACARE-REPEAL PUSH DRAWS OBAMA INTO FIGHT

The competing – and often contradictory – narratives and statistics on health insurance complicate efforts to dissect the data. But the overall trend lines still appear to be going in the wrong direction, upping the pressure on Congress to find a fix.

“ObamaCare is absolutely imploding,” Rep. Trent Franks, R-Ariz., told Fox News’ “America’s Newsroom.”

One glaring symptom of the ACA’s challenges has been the fate of consumer operated and oriented plans, or co-ops. These small nonprofit insurers were created to boost competition, expand the number of health insurance providers available in rural areas and in turn lead to lower prices for coverage.

But that’s not how it’s played out.

In 2014, there were 23 co-ops operating across the country. By 2015, all had posted annual losses, according to the National Alliance of State Health Co-Ops.

Since then, financial insolvency has claimed all but four.

The latest co-op casualty is Minuteman Health.

The company, which has around 37,000 customers in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, called it quits in late June. (The company plans to reopen as a for-profit in January 2018.)

CEO Tom Policelli blamed the exit on a provision in the ACA that requires insurers with healthier customers to make payments to insurers with sicker customers. Policelli called the risk adjustment program “highly volatile.”

Larger insurers have also begun to bolt certain states, leading to reduced options for consumers in the individual market.

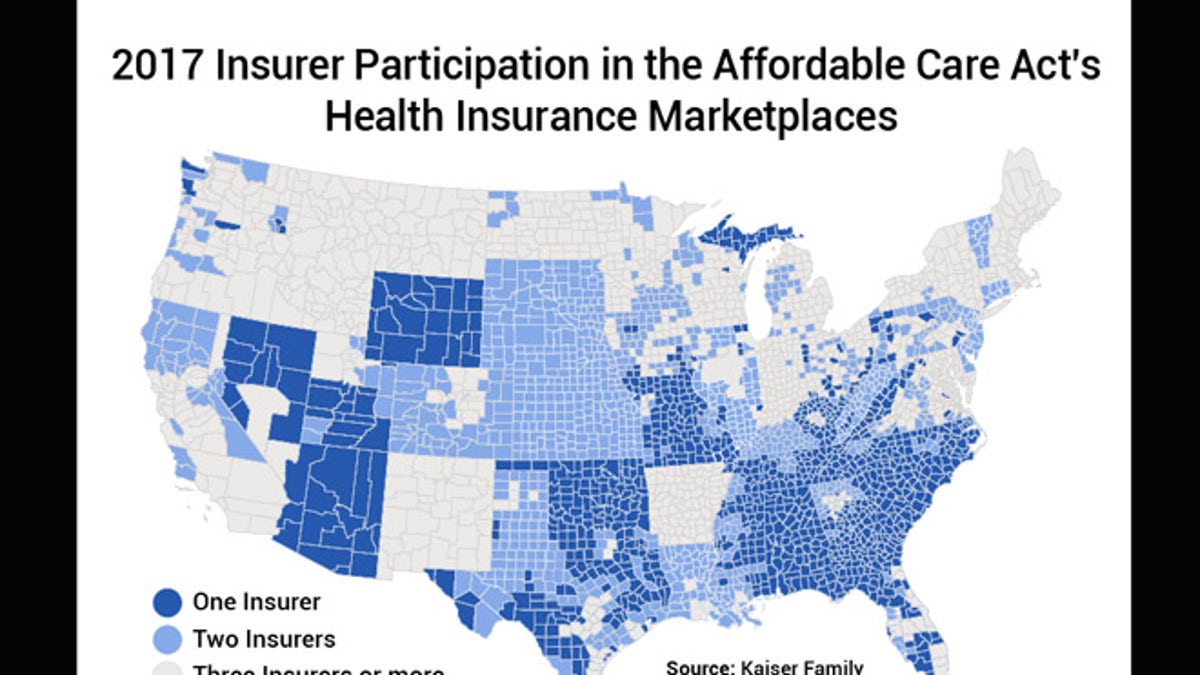

A June Kaiser Family Foundation analysis estimates 38 out of 3,143 counties – or about 1.2 percent – could be at risk of having no insurer on the marketplace in 2018. This year, roughly a third of counties have access to just one insurer on the marketplace, according to the report.

That’s a hard fall for the ACA, which touted an average of five insurers participating in each state ACA marketplace in 2014. In 2015, that average bumped up to six insurers per state, ranging from one in West Virginia to 16 in New York, according to Kaiser. Things took a turn in 2016 following the failure of several co-ops, which brought the average down to 5.6 per state. In fiscal 2017, big insurance losses led to high-profile exits dragging the average down even more to 4.3.

The decision by health insurance giants Aetna and Humana to pull out of some state exchanges has rattled other insurers and raised concerns over the stability of the individual market.

In June, Anthem announced it would pull out of Ohio’s marketplace leaving some counties with no insurers. Anthem’s exit was particularly bruising because the state had been one of the most competitive marketplaces in the country. In 2016, 17 insurers sold plans in Ohio.

Anthem didn’t mince words about why it was leaving. The company cited a lack of certainty around billions of federal dollars in subsidies they thought were coming their way as well as a lack of “overall predictability.”

Under ObamaCare, insurance subsides are doled out though refundable tax credits for individuals making between $16,000 and $47,000 per year as well as through cost-sharing reductions, where additional subsidies are paid by the government directly to insurers to help lower the amount customers pay for deductibles and co-pays.

The Trump administration has been vague about whether they’ll pay and has said the president could decide to nix the subsidies whenever he wanted, creating more market confusion.

During the campaign season, Republicans seized on the uncertainty and cited rising insurance premiums as the primary reason ObamaCare needs to go. It’s a fight that continues to this day.

Unlike candidate Trump who made bold statements about what he would do to get rid of ObamaCare and the speed with which he would do it, President Trump and his administration have waffled on ways to stabilize the insurance markets. The president even has suggested a few times letting it implode.

Trump tweeted “Death spiral!” following Aetna’s announcement that it would pull out of the Virginia ACA exchange in 2018. When Humana announced its exit, Trump claimed, “ObamaCare continues to fail.”

The comments did little to soothe growing concerns of instability.

Some insurers still willing to offer plans under ObamaCare have braced themselves for financial hits by hiking premiums – though how much varies.

According to Kaiser, customers in Phoenix, Ariz., are facing a 145 percent increase whereas in Providence, R.I., customers could see a 14 percent decrease.

But those numbers could change for the worse.

A lot of what happens next with ObamaCare depends on if the Trump administration and Republican-controlled Congress – let alone Republicans and Democrats – can get on the same page.

Industry watchers warn that until the White House and Capitol Hill can present a united front, even more dramatic premium hikes will be passed on to customers.