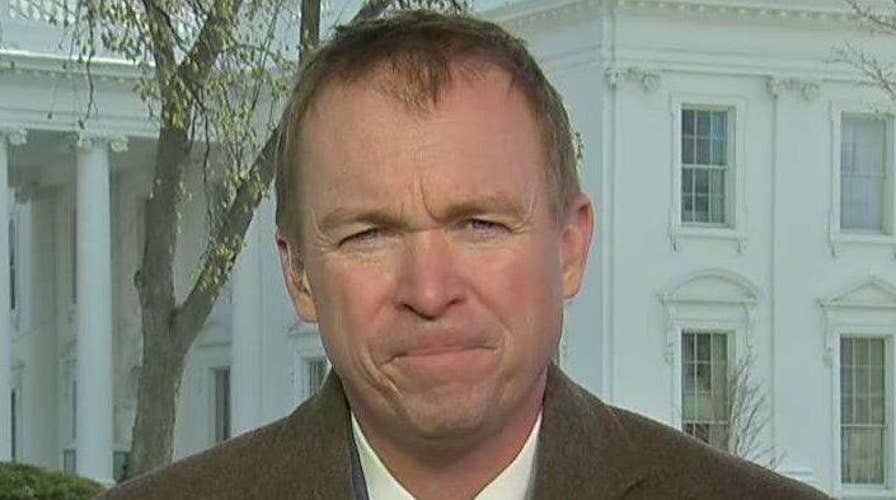

Mulvaney: White House budget focuses on country's priorities

On 'Special Report,' the Director of the Office of Management and Budget says the budget targets ineffective government programs

When it comes to President Trump’s $1.065 trillion budget, the words will help you understand the numbers.

Let’s start two weeks ago when White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney strode into the press briefing room and opined on a “budget blueprint.”

The term “blueprint” is important here. Mulvaney declared that he and President Trump were engineering an “America First” budget that would not be “adding to the deficit.” He declared that the “topline defense number is the largest in history.” Mulvaney then indicated that Trump would spend “$603 billion” on defense programs and “$462 billion” on “non-defense.”

That means Congress would cough up a total of $1.065 trillion in “discretionary” spending. But when it came to “mandatory” spending, the budget director told reporters, “that won’t come until May.”

Mulvaney argued the prototype “wasn’t a full-blown budget.” His pecuniary jabberwocky doesn’t mean much to most Americans. But let’s decrypt the code.

Think of a big pie totaling around $4 trillion. The $4 trillion pie represents each dollar the federal government spends on every single program imaginable. This pie is the true federal budget. Trump and Mulvaney still haven’t cobbled together that package yet.

Then bring out a knife and slice the pie into two sections. One slice comprises about 69 percent of the pie, or a little more than two-thirds. That’s known as “mandatory spending.”

Mandatory spending isn’t mandatory, per se. It’s simply money Congress put on auto-pilot long ago. It flows out the door without lawmakers flagging any of it. Mandatory spending covers Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and interest on the debt. Congress could certainly reclaim that huge slice of the pie if lawmakers wanted. But they haven’t -- yet.

The second piece of the pie is trickier. This is discretionary spending. This is the blueprint Mulvaney released two weeks ago. He amplified it Thursday with more specific spending targets for a variety of agencies and departments.

Take the discretionary spending chunk and convert it into its own, standalone, second pie. Then divide that pie into 12 uneven pieces. Each piece represents one of the 12 appropriations or spending bills which fund the government each year.

A failure to approve any of those bills in Congress and secure the President’s signature prompts a government shutdown.

The size of last year’s discretionary spending pie was $1.070 trillion. Defense consumed nearly half of the pie. Other pieces were smaller. The Agriculture appropriations bill came in at $21.8 billon. The Interior appropriations bill clocked in at $32 billion. Legislative branch was $4.4 billion. State/Foreign operations was $37.8 billion.

You get the idea.

The State Department and Environmental Protection Agency took a whack under Trump’s blueprint, losing about a third of its funding. On life support is the National Endowment for the Arts and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Mulvaney says cuts will come from 11 of the 12 spending bills to increase the size of the military slice.

There’s an appropriations bill called Military Construction/VA. It funds the Department of Veterans Affairs and last year cost $79.9 billion.

Lawmakers won’t trim much there because it looks bad to ding veterans. How about Homeland Security? $41 billion last year. Well, Trump wants more money for the border patrol and customs/immigration officials.

So, to make up the extra $54 billion, he wants to divert to the Pentagon slice of the pie, cuts could come from the remaining nine slices, not 11 – excluding Military Construction/VA and Homeland Security.

Therein lies the problem.

The House struggled last year to find enough votes to pass appropriations bills. The reason? Conservatives and members of the Freedom Caucus thought some spending bills cost too much. Moderate and “mainstream” Republicans argued the bills didn’t spend enough.

So the GOP lost votes at the margins. Help from Democrats? Forget it. They didn’t like anything they saw. As things now stand in the House, the GOP can only lose 22 votes before the leadership can’t pass a bill on its own. How about the Senate? Well, senators need 60 votes to call up appropriations bills and shut off debate. Very hard when Republicans only have 52 yeas in the Senate.

The House GOP brass yanked several appropriations bills off the floor last year. The Financial Services Appropriations bill flat-out failed on a floor vote.

The problem is that Republicans need to fund things besides the military. The size of the non-defense spending bills could be too puny to sustain large reductions.

Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, is a senior member of the Appropriations Committee and is what is called a “cardinal.” That means Simpson is the chairman of one of the appropriations subcommittees: the Energy and Water panel.

Lawmakers refer to colleagues like Simpson as a cardinal because of the “divinity” or “eminence” they wield over their section of spending.

“I don’t think you can pass any of the bills,” Simpson said. “You can’t get there from here.”

Growing the Pentagon budget is good politically. But it may not be practicable.

“A lot of members have interest in these programs,” Simpson continued. “There’s a lot more to our government than defense.”

Could Trump be picking a fight with Capitol Hill so he has a foil?

“Setting up Congress? Hell, every president does that. ‘It’s the damn House!’” Simpson exclaimed.

Is the Senate able to stomach a measure slashing diplomatic funding?

“Probably not,” predicted Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. “I think the diplomatic part of the budget is important and a lot cheaper than the results you get on the defense side.”

House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Ed Royce, a California Republican, fretted: “I am very concerned that deep cuts to our diplomacy will hurt efforts to combat terrorism, distribute critical humanitarian aid and promote opportunities for American workers,”

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y, predicated Democrats and Republicans alike will “run away.”

“We’ve already cut EPA,” said Rep. Mark Amodei, a Nevada Republican and a member of the Appropriations Committee. “That’s going to be on our mind when it comes to cutting more.”

Trump’s budget pruned grants for federal housing programs that assist the elderly and poor. That could make it hard for Congress to OK the Transportation, Housing, Urban Development & Related Agencies spending bill, piloted by cardinal and Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart, R-Fla.

Pennsylvania GOP Rep. Charlie Dent, the chairman -- or cardinal -- of the Military Construction/VA panel predicted: “The budget in this form will make it very difficult to pass many appropriations bills.”

All of these cuts are from the smaller pie, with none from entitlement spending like Medicare and Medicaid, far and away the biggest drivers of the debt.

Mulvaney promises a look at that in May.

“We targeted programs that sound great but that don’t work,” said Mulvaney in an interview Thursday with on Fox News “Special Report” host Bret Baier. “These are programs that sound great. Many of them Democrat programs.

Many of them 30 years. They’ve never been reviewed in a long time or when they’re reviewed, they’re just not producing any results.”

Some conservatives embraced the spending outline. Rep. Louie Gohmert, R-Texas, is happy about filleting the State Department’s allocation.

“They were promoting an LBGT agenda,” he said.

“We went to African countries, telling them, ‘Yes, we will help you with Boko Haram if you change the law in your country and allow same-sex marriage and pay for abortion.’ ”

GOP Defense hawks like House Armed Services Committee Chairman Rep. Mac Thornberry, Texas, and Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain, Arizona, still want more for the Pentagon. They’d like as much as $640 billion to go toward defense programs.

But Dent noted that regardless of what the president and Mulvaney request, it’s just that. A request.

“The president proposes. The Congress disposes,” he said. “Congress will write the appropriations bills.”

“If the House and Senate do it a different way, that’s fine,” Mulvaney said. “We would be happy to negotiate with them.”

Here’s the secret. Members of Congress -- even Republican members of Congress -- will attempt to craft the 12 appropriations bills in a way that can pass.

House Appropriations Committee Chairman Rodney Frelinghuysen, R-N.J., will design a discretionary spending allotment (the smaller pie) known as a “302(a).”

He will then dice the pie into its 12 pieces for each subcommittee. The individual pieces are called “302(b)’s.” Then subcommittee chairmen like Simpson, Dent and Diaz-Balart hope to write bills in a way they can pass.

The question is whether Trump would sign bulkier bills into law. This could spark a remarkable standoff between the Republican president and members of his own party -- especially if GOP members can’t agree on the size of each bill.

The president touts his negotiation skills. Mulvaney says the administration is willing to talk. There’s a lot of speculation on Capitol Hill that these budget outlines are merely opening bids.

Here’s the key takeaway: Mulvaney’s two budget proposals aren’t binding. The word “budget” is a malleable term in the federal spending lexicon.

Congress never adopts the budget a president sends to Capitol Hill. If and when the House and Senate approve a budget (the big pie), that is only a resolution, not a binding law. The president does not sign a “budget.”

What the president must sign are the 12 annual appropriations bills that comprise the smaller pie. Otherwise, there’s a government shutdown.

So these are the words that help explain the numbers. Budgets are wish-lists. Consider that when the president wants to slash art funding, Meals on Wheels or bolster the military. It’s just an ambition.

What counts are appropriations and 12 pieces of the smaller pie. Appropriations are real. And we’ll see how much the president is willing to negotiate on those.