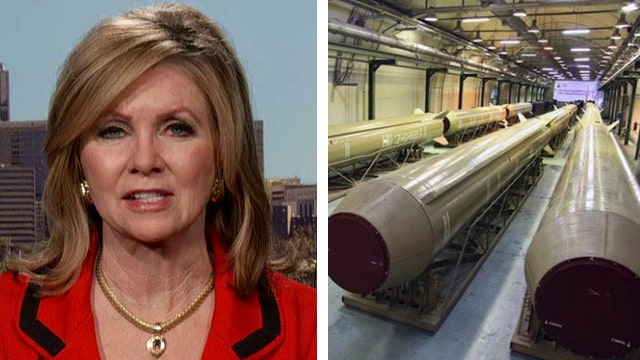

Blackburn: Any Iran deal must have transparency

Deadline for the framework of a nuclear weapons program agreement coming down to the wire amid warnings from lawmakers about a bad deal

The Obama administration is charging into a Tuesday deadline for striking a nuclear deal with Iran -- despite mounting warnings about Tehran's role in the deadly Yemen unrest, the Arab League uniting against Iran-aligned forces there and worries that a weak deal could trigger a regional arms race.

"A bad deal, Mr. President, leads to a nuclear arms race in the Mideast. It puts Israel in an untenable situation," Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said Monday.

The White House has long put the chances of a deal at "50-50." And it appeared talks could indeed come down to the March 31 deadline for a framework deal that would be the basis for a final accord, to be reached by the end of June.

White House spokesman Eric Schultz, briefing reporters on Air Force One on Monday, said talks would "go down to the wire." He said that he would not "presuppose failure" and that U.S. officials are working around the clock in earnest.

President Obama, meanwhile, speaking at an event in Boston marking the opening of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute, defended the talks -- saying Secretary of State John Kerry is standing for the principles Kennedy believed in: "Let us never fear to negotiate."

The deadline arrives at an awkward and challenging time, with Iran accused of backing Shiite rebel militias in Yemen that have thrown the country into chaos.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, at the forefront of accusations that Iran helped Shiite rebels advance in Yemen, says the deal in the works sends the message that "there is a reward for Iran's aggression."

Meanwhile, speculation is mounting that Saudi Arabia and other nations could pursue a nuclear weapon if a deal struck with Iran is not strong enough.

Graham, one of the toughest critics of the talks, told FoxNews.com's "Defcon 3" that "if you do a deal where the Arabs feel like [Iran is] a threshold nation, the Arabs are going to want to bomb [Iran] themselves."

Graham seemed to describe the details emerging from the current talks as pointing toward what he would deem a bad deal, calling U.S. negotiators "clueless." A good deal, Graham said, would "allow [Iran] to have a nuclear power program that can't be used to make a bomb."

In a sign that a deal is unlikely on Monday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov was leaving the talks, just a day after arriving, to return to Moscow for previously planned meetings, according to his spokeswoman. Lavrov will return to Lausanne, Switzerland, on Tuesday if there is a realistic chance for a deal, she said.

All sides are still scrambling to reach common ground.

The New York Times reported late Sunday that, in the latest twist, Tehran had backed away from a tentative promise to ship a large portion of its uranium stockpile to Russia, where it could not be used as part of any future weapons program.

Schultz disputed some details in that report, suggesting there was no agreement with regard to shipping the stockpile to begin with. He reiterated that nothing is agreed to until everything is agreed to, and said the stockpile issue is still being worked out.

If Iran insists on keeping its uranium in the country, it could undermine a key argument made in favor of the deal by the Obama administration. The Times reported that if the uranium had gone to Russia, it would have been converted into fuel rods, which are difficult to use in nuclear weapons.

It is not clear what would happen to the uranium if it remained in Iran. One official said Monday that Iran might deal with the issue by diluting its stocks to a level that would not be weapons grade.

The stockpile is just one of several sticking points left to be addressed in the final hours.

The Associated Press reported Sunday that Iran's position had shifted from demanding that it be allowed to keep nearly 10,000 centrifuges enriching uranium, to agreeing to keep 6,000. Western officials involved in the talks told the Associated Press that Tehran may be ready to accept an even lower number.

But negotiators are still debating over the length of the deal, the pace at which sanctions could be lifted and the projected time Iran would need to crank out a nuclear weapon if it took that step.

The Obama administration says any deal will stretch the time Iran needs to make a nuclear weapon from the present two to three months to at least a year. But critics question that, and say it would be flawed because it keeps Tehran's nuclear technology intact.

Officials also told the Associated Press that Iran wants a total lifting of all caps on its activities after 10 years, while the U.S. and the five other nations at the talks -- Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany -- insist on progressive removal after a decade.

A senior U.S. official characterized the issue as lack of agreement on what happens in years 11 to 15.

One official said Russia also opposed the U.S. position that any U.N. penalties lifted in the course of a deal should be reimposed quickly if Tehran reneged on any commitments.

Both Western officials said Iran was resisting attempts to make inspections and other ways of verification as intrusive as possible.

In a tweet, Gerard Araud, the French ambassador to the United States, said "very substantial problems remain to be solved."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.