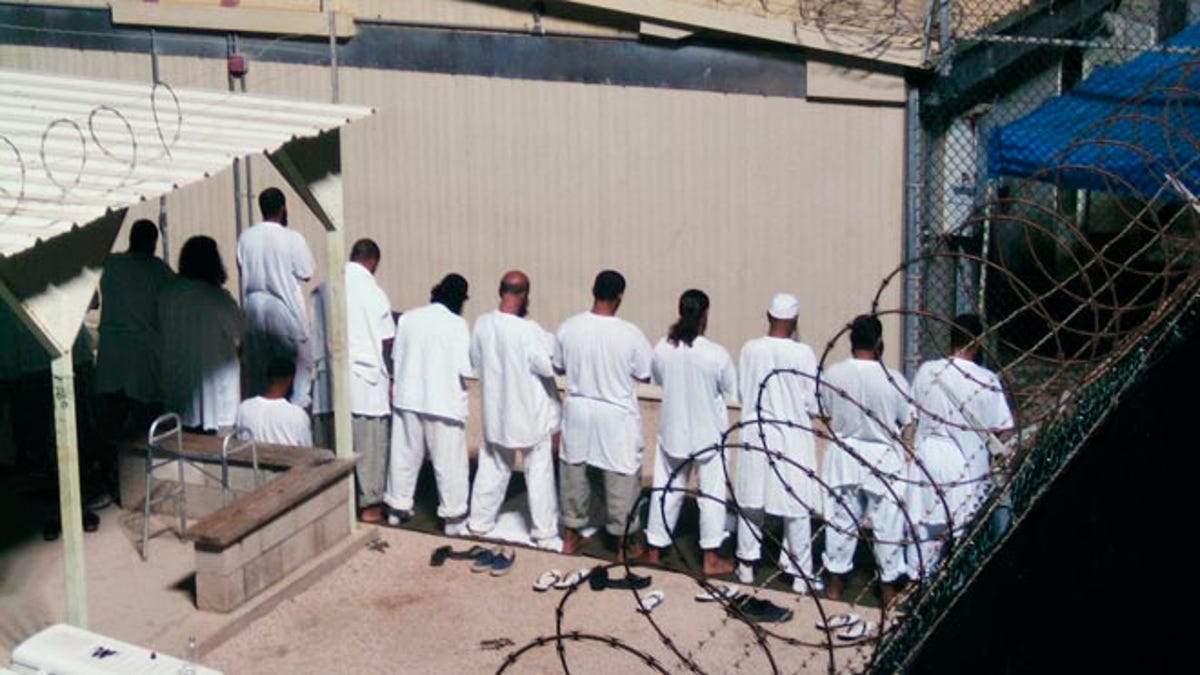

FILE: 2009: Detainees prayer at a detention facility at Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, in Cuba. (REUTERS)

A federal court has dismissed a Guantanamo Bay detainee’s recent petition for release when the United States ends its war in Afghanistan, but the case continues to highlight the fast-approaching situation in which the last American troops will leave the Middle East country and the U.S. must decide on the future of the facility’s remaining detainees.

Detainee and suspected Taliban affiliate Fawzi al Odah made his request based on the argument that the U.S. cannot hold detainees after ending “military hostilities” in the so-called war of terror and President Obama’s statement earlier this year that the Afghan war is ending.

U.S. District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly said in her August 3 opinion that Odah’s case was not “ripe” because the war has yet to end and was “dependent on future events that may not occur as anticipated, or may not occur at all.”

However, she also suggested that U.S. officials have an “apparent” legal responsibility to release remaining detainees -- reigniting the debate about the future of the Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, facility, created in the aftermath of 9/11 terror attacks.

Charles Stimson, a Heritage Foundation national security and foreign policy expert, said earlier this week that the “common sense” interpretation of the law of war, which dates back a thousand years, is that detainees are released when the hostilities ends.

“But Gitmo has always been a political football for Democrats and Republicans, when it’s convenient,” he said.

To be sure, the future of Guantanamo and its detainees as well as Obama’s legal authority to hold them was already the subjects of contentious Washington debates.

President Obama has from the start of his presidency in 2009 tried to close the facility at the Guantanamo Naval base, starting with an executive order that called for its closure within a year.

Meanwhile, Capitol Hill Republicans have essentially led the argument against closing the facility, largely on the basis of having to move terrorists onto U.S. soil or release them.

In fact, the GOP-led House, as recently as May, rejected a Democrat-sponsored amendment, based on cost concerns, to establish a framework for closing the facility before 2017.

The last of the roughly 8,700 U.S. troops planned departure from Afghanistan in 2016 is largely being considered the official end of the hostilities.

But how long the U.S. can hold the detainees appears less clear, even for the administration.

“To the extent we’re no longer in a conflict with the Taliban, there may not be a basis to hold those individuals,” Lisa Monaco, a White House counter-terrorism adviser, said last month.

She argued the legal basis for capturing and detaining terrorists is the post 9/11 Authorization to Use Military Force, while also pointing out the statute is “quite brief” and has no “time de-limiter” on it.

Stimson also argues that Judge Kotelly’s opinion about the federal government’s legal responsibility was narrowly focused on Taliban detainees.

As a result, he says, the administration could be in a “dicey situation” regarding what to do with al Odah and other detainees also found to be affiliated with the still-active Al Qaeda terror group.

Al Odah, a Kuwait citizen, was captured in Tora Bora, Afghanistan, in December 2001. Eight years later, a federal court concluded after a three-day hearing that a “preponderance of evidence” showed he “more likely that not” had been a part of the Taliban and Al Qaeda, according to court documents.