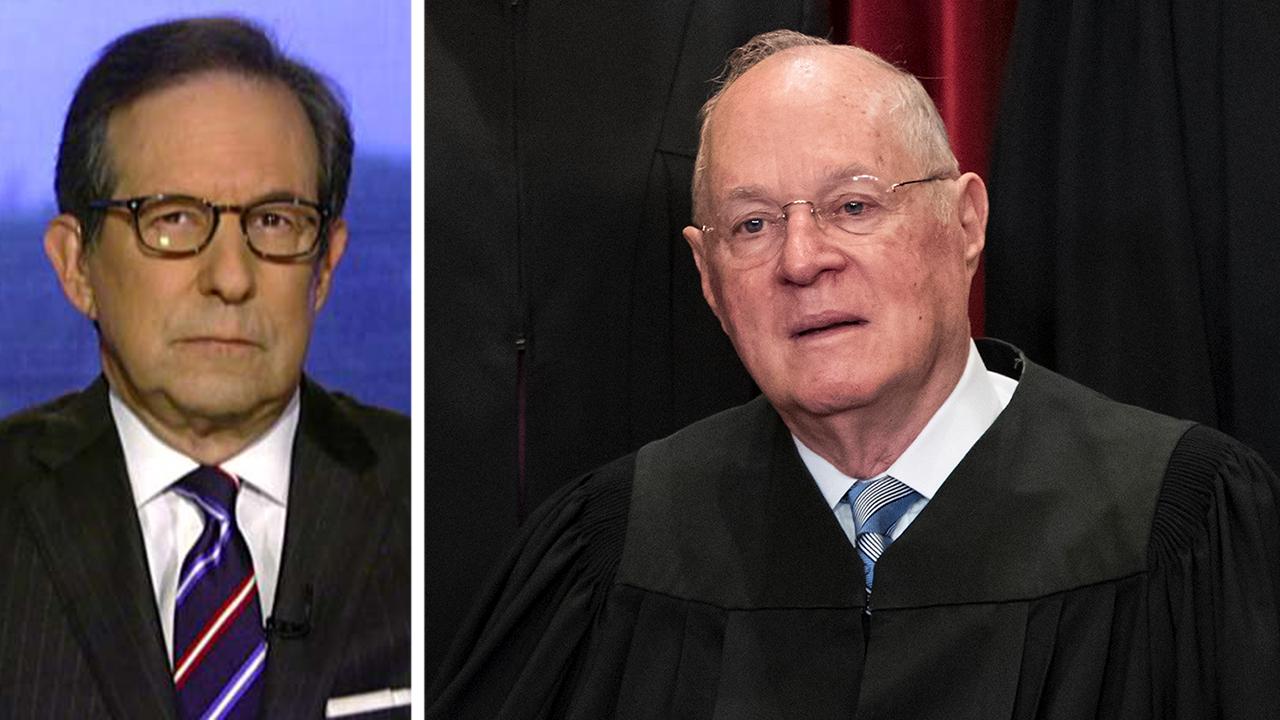

Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy speaks to faculty members at the University of Pennsylvania law school, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2013, in Philadelphia. Kennedy is teaching this week at the University of Pennsylvania law school.(AP Photo/Matt Slocum) (AP)

A low-key California judge seemed the right man at the right time, a perfect antidote for a White House and Congress left angry and exhausted. The Senate confirmation of Anthony Kennedy in 1988 to sit on the Supreme Court ended the long and contentious political process of selecting a successor to Justice Lewis Powell. After two failed nominations, President Ronald Reagan went a familiar route, nominating an old acquaintance from his days as California governor.

In his decades on the court since that unusual beginning, Kennedy has crafted a powerful, if hard to define, judicial legacy -- seemingly in the forefront of every major ruling during his tenure. As an unapologetic "swing" vote, he was the key behind-the-scenes architect of the 2000 Bush v. Gore drama, and a 1992 opinion upholding abortion rights. He wrote majority decisions upholding rights for homosexual couples, underage killers and foreign fighters held by the U.S. military in the war on terror.

The 81-year-old Kennedy announced Wednesday he planned to retire from the high court, informing President Trump in a letter.

"The basic principle is, it was Justice Kennedy's world and you just lived in it," said Thomas Goldstein, a private appellate attorney and creator of scotusblog.com.

Kennedy shared the role of the "decider" with fellow westerner Sandra Day O'Connor before she retired in January 2006.

Anthony Kennedy facts

- Born 1936

- Sacramento native

- Nominated in 1987 by President Reagan

- Filled Seat held by Justice Lewis Powell

- Considered a moderate-conservative justice

- Reagan's third choice after Robert Bork, Douglas Ginsburg

- Created "Dialogue of Freedom" forums for students after 9/11

- Former law professor, federal judge

- Often cast pivotal swing vote in important cases

- Strong free speech advocate

- Family friend of late Chief Justice Earl Warren

- Upheld abortion rights in 1992

"On a court of nine members, there almost has to be someone in the middle by definition. And Justice Kennedy was our swing vote," said Goldstein. "His job where he sat on this court was to cast the deciding vote sometimes."

So in hindsight, it may come as a surprise this influential justice was not the White House's first choice for the high court. Or the second.

It was 1987, the 200th anniversary of the U.S. Constitution, and a Supreme Court vacancy promised to change the political and social order. Powell, a courtly Virginian, was then the court's moderate, keeping the bench from tilting too far left or right. His replacement could upset that balance.

The president's first choice was ultra-conservative Robert Bork, who faced withering resistance from Democratic senators, and was ultimately rejected. Then came Douglas Ginsburg, more subdued but no less controversial. The federal judge withdrew his nomination after admitting he had smoked marijuana as a college professor years earlier.

"The White House and the Department of Justice were quite frankly exhausted," recalled Douglas Kmiec, who led the initial screening of high court candidates as a Reagan administration lawyer. "That led to voices in the department who knew Anthony Kennedy as a responsible, sure and steady Republican voice, to ultimately prevail." But Kmiec and other strong conservatives were worried. "I was present at the creation," he said. "He was number three for a reason."

But the administration and Democrats seemed eager to end the political nastiness, and Kennedy sailed through his Senate confirmation, despite concerns from many liberal activists the newest justice was too conservative. Neither political side, it seemed, could grasp who Kennedy really was, a trend that remained until the day he would retire.

"There was a perception, and an accurate one, that he would play better on television than Judge Bork had," said Brad Berenson, a former Kennedy law clerk.

Reagan was clairvoyant when introducing his final high court nominee. "I'm certain he will be a leader on the Supreme Court," said the president, adding, "The experience of the last several months has made us all a little wiser." Consensus had its price, and many Republicans still lament what could have been.

The newest justice jumped into his new job with relish. Colleagues recall an initial awestruck, almost giddy manner with his newfound stature, often seen bounding up marble stairs with his long strides, and delving deep into the court's history, even the Supreme Court building's architecture and infrastructure.

Along with O'Connor, the two native westerners carved out a jumpy place in the center. Less driven by practical concerns than O'Connor, Kennedy strove for a loftier sense of the law's impact on society.

"There was a grand eloquence to his writing," said Edward Lazarus, who clerked on the high court during Kennedy's first full year on the bench. With the justice often using amorphous language, Lazarus believed he retained "an idealized sense of what it meant to be a judge, and he wanted to fulfill that very exalted vision of what the third branch of government should be about."

That love of the law was nurtured early in Anthony McLeod Kennedy's life. Born in 1936 in Sacramento, his father was a well-respected, well-connected, and popular local attorney. He passed on to his children a love of learning and social responsibility. Kennedy himself described his youth as "kind of a study nerd."

Kennedy always assumed he would be a lawyer, and later took over his dad's law firm, while also teaching part time at McGeorge Law School, which he continued even after he joined the high court. His political connections, straight-arrow image, and California conservative views led to President Ford naming Kennedy to a federal appeals court seat in 1975. Soon after, he became a top-tier high court candidate.

"He brought to the bench a combination of a very scholarly, erudite, academic bent," said Berenson, "and a very practical bent he had developed while practicing law on his own."

His early years on the Supreme Court produced a fairly consistent conservative record, but he often resisted efforts by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia to go further right than he was comfortable going.

For him, 1992 was a turning point with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, where the justices upheld the right to abortion, and said government could not create any "undue burden" for women seeking access to the procedure.

Recently released private memos from former Justice Harry Blackmun reveal Kennedy was at first prepared to overturn Roe v. Wade, but then changed his mind. He joined a three-justice coalition that carved a centrist position upholding the basic abortion right, but giving government some leeway to craft "reasonable" restrictions.

Kennedy famously summarized his views on the larger issues at stake in Casey: "At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life."

"It was a very difficult decision for Justice Kennedy, and I think he was swayed by his colleagues and a sense of history," said Lazarus. "But because he changed his position, he really earned this reputation as someone who could be gotten to in these hot-button cases and drawn away from his natural conservative ideology."

That earned him nicknames inside and out of the court: Flipper, Errant Voyager, Man in the Muddle. Kennedy's complex, some say unique, views on the law leave little room for consensus among his supporters and detractors.

"Justice Kennedy is a man who really doesn't know his own mind," said Kmiec, now a law scholar. "And that's not meant entirely as a criticism, because the positive way to say that is: he's open-minded."

"He has not been a justice to look at overarching principles, one rule that settles every case," said Orin Kerr, his law clerk from 2003. "His decisions are considered unpredictable because he's not always going to rule in favor of the government, he's not always going in favor of a defendant. He's going to look case by case and that makes his decisions distinctive."

Kennedy's "Greatest Hits" as the key author or swing vote on the high court could fill multiple volumes. Among the cases he supported:

- A 1989 decision allowing juvenile killers to be executed, then 16 years later wrote the opinion overturning such punishment, citing "the overwhelming weight of international opinion" against it.

- A 1992 decision barring government-sponsored prayer at high school graduations.

- The overturn of a Texas law banning consensual homosexual sex had the Kennedy stamp with his 2003 legal conclusions: "The petitioners are entitled to respect for their private lives. The state cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime."

- Race-based factors in the assignment of children to public schools in America were ruled unconstitutional in 2007. While siding with the majority, Kennedy's concurring, moderating views provided the controlling legacy for the use of racial criteria in the future. Kennedy believed race could still be used in very narrow circumstances to ensure integrated schools. "A district may consider it a compelling interest to achieve a diverse student population," he said.

- Legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide, perhaps his most important ruling. "No longer may this liberty be denied," he wrote, affirming gay and lesbian couples deserve "equal dignity in the eyes of the law."

He generally supported his conservative colleagues on issues of crime, the death penalty, states’ rights, and civil rights. But also backed the left on abortion, homosexual rights, and school prayer.

Then there was the court's dramatic intervention in the 2000 fight over the presidential election, and whether Florida could continue counting disputed ballots in several counties. Court sources who were involved in the internal deliberations said Kennedy alone among the justices believed the issue was about due process, the idea that individuals enjoy procedural rights in many types of court proceedings, while also substantively limiting government power.

As justices from the left and right courted Kennedy's vote, he ultimately went much his own way, rejecting the standards for a recount ordered by Florida's top court. He concluded that violated due process and equal protection guarantees, since it infringed on the state legislature's prerogatives.

The Supreme Court's controlling opinion in Bush v. Gore was unsigned, but court sources say it was written mainly behind the scenes by Kennedy and O'Connor.

"The other conservative justices needed Justice Kennedy," said Lazarus, "and his views were idiosyncratic largely to him."

Almost every friend and colleague who knows Kennedy has remarked how seriously he took his job and how hard it often was to make up his mind. "Conflicted" is a word used frequently, reflecting his desire to see all sides of an issue before deciding.

Kennedy himself acknowledged the unique role he played for decades on the court. "There is a loneliness" to his job, he once said.

Never more so than when a few members of Congress wanted him "fired" from his lifetime job on the bench.

Kennedy refused on his own in 2005 to allow the Supreme Court to get involved in a state dispute over whether a brain-damaged Florida woman's feeding tubes could be removed. Terri Schiavo's husband and parents were deeply at odds over whether her life should be ended, and lower courts sided with her husband, Michael.

Congress passed an emergency bill signed by President Bush urging the federal courts to intervene, but the high court refused.

"The time will come for the men responsible for this to answer for their behavior, warned then-House Speaker Tom DeLay, the day Schiavo died.

Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, mused about how a perception that judges are making political decisions could lead people to "engage in violence." Other lawmakers suggested impeachment hearings, and an inspector general to audit, investigate, punish judges for their decisions.

Kennedy also incurred conservative outrage over his outspoken public opposition to a House bill imposing tough mandatory minimum prison terms for certain criminal offenses. The justice said that would lead to overly harsh sentences.

"On a court of nine members there almost has to be someone in the middle by definition. And Justice Kennedy was our swing vote.

That judicial confidence in his own role, and that of the court he helped shaped was long evident. Judges, he once said, have power and duty to "impose order on a disordered reality."

"Justice Kennedy's critics would say he has been a bit pompous on the court and a bit self-aggrandizing, and that's had substantive results," said Lazarus. "There was no modesty about the court when Justice Kennedy was there, and his view of judicial power, and the fact he's comfortable with it has played a role in all that."

Kennedy's affable nature earned him respect as a thoughtful and respected jurist, and while his legacy may remain as elusive as his judicial philosophy, his impact on the law in his more than three decades on the court is little in doubt.

“There were always some very hardcore conservatives that were disappointed" in Kennedy, said Berenson. "But by and large, his basic decency insulated him from a lot of criticism and vituperation."

As for Kennedy himself, "Sometimes people think compromise means squishy, centrist," he once said. "It doesn't."

This man of ideas hoped he would be remembered as, "Somebody who's decent, and honest and fair, and who's absolutely committed to the proposition that freedom is America's gift to the rest of the world."