This week marks 75 years since a B-29 bomber dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945.

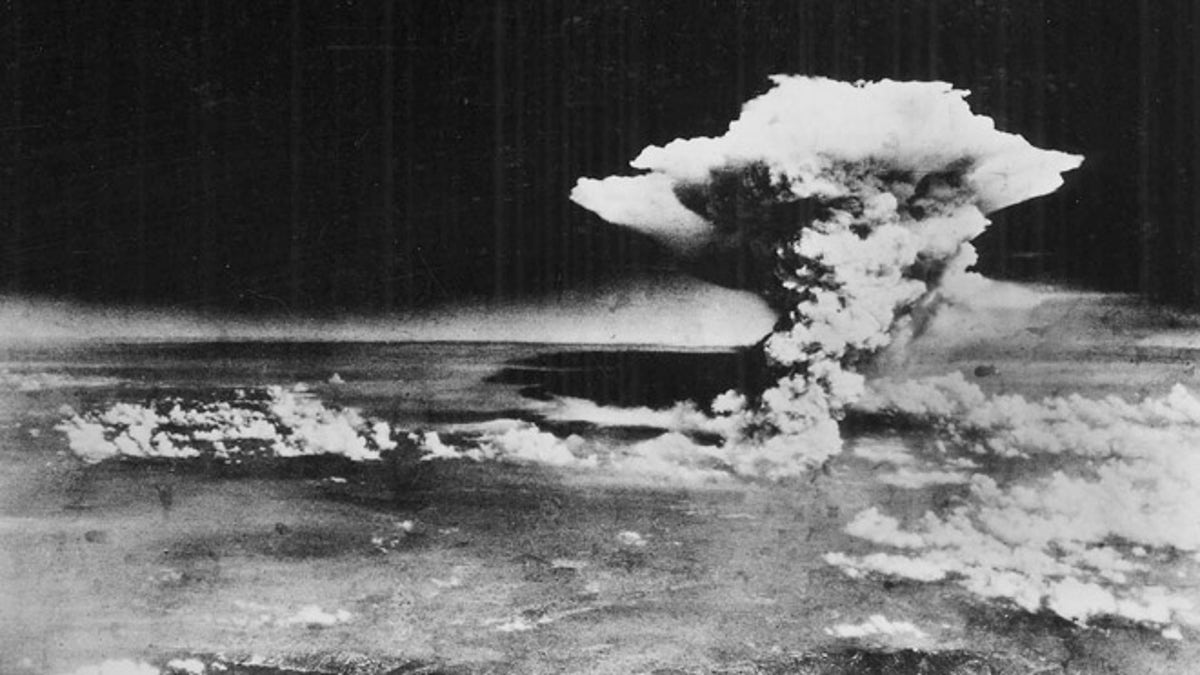

From his turret in the rear of that B-29, tail gunner Bob Caron saw the mushroom cloud spreading over Hiroshima. It was “a bubbling mass of purple-gray smoke and you could see it had a red core in it and everything was burning inside” the Army staff sergeant from Brooklyn observed. On the ground, about 70,000 were killed by the blast.

Why? To obtain unconditional surrender from Imperial Japan and end World War II.

REBECCA GRANT: 'RUSSIA EXPERTS' TOO BUSY RAILING ON TRUMP TO SEE REAL THREATS RIGHT IN FRONT OF US

The man who made the final decision to drop the atom bomb was President Harry S. Truman. “I had realized, of course, that an atomic bomb explosion would inflict damage and casualties beyond imagination,” Truman later wrote.

But Harry Truman was uniquely qualified to make this decision. Out of all U.S. presidents in the 20th century, only Truman experienced sustained, ground combat.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR OPINION NEWSLETTER

Truman commanded an artillery battery during World War I. His Battery D of the 129th Field Artillery fired 3,000 rounds in four hours to open the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in September 1918, the bloodiest American battle of the Great War. Over a million U.S. soldiers took part with 26,000 killed in action and 120,000 wounded.

Truman never sought to glamorize his military service. Leaving New York Harbor for France, he recalled watching the city skyline diminish and wondering “whether we’d be heroes or corpses.” “Most of us got by without being either,” he remarked in his short autobiography.

More from Opinion

In France, he admitted to terror at taking command over the rough, obstreperous Irish Catholic and German men from Kansas City who made up Battery D. As it turned out, they liked their 34-year-old captain with the round eyeglasses and he led them well.

Ironically, Truman participated in the end of World War I first-hand. Fifteen minutes before the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, Capt. Truman was still firing at the Germans north of Verdun with Battery D’s 75 mm gun, trying out an impressive new shell reaching 11,000 yards.

Like most veterans of World War I, Truman glossed over the gore he witnessed. But his combat experience stayed with him and this was the outlook Truman brought to his decisions on the atomic bomb in 1945.

Just as a younger Harry Truman had seen a lot on the Western Front, the war in the Pacific in 1945 was at a peak of brutality. Americans suffered horrendous casualties on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Kamikaze Japanese suicide planes attacked and flamed Navy carriers and ships. B-29s had been firebombing Japan’s major industrial cities to destroy the wiring and controls and machinery of Imperial Japan’s heavy war industry. The March 9, 1945 firebombing of Tokyo killed as many as 125,000 in one night.

The two atomic bombs, and the fear of more, gave Japan a reason to surrender.

As Truman knew, Japan was losing but unwilling to give up. In Europe, over 5 million German soldiers opted for surrender during battle. In the Pacific war, Imperial Japan forced a fight to the death. Less than 5 percent of Japanese forces surrendered in battle.

Looming ahead was the invasion of Japan, scheduled for Nov. 1, 1945. It would start with Gen. Douglas MacArthur commanding amphibious landings on Kyushu, the southern tip of Japan. Japan’s warlords correctly guessed the invasion site and had already poured in 200,000 troops with more massing daily. A fresh 8,000 kamikaze planes were on hand.

Imperial Japan’s strategy was to inflict unacceptable losses on invading American forces, bog down the fight and play for time to negotiate terms other than unconditional surrender. Hundreds of thousands would have died in the process.

With the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945, the allies gave Japan a chance to end the war. Japan rejected it July 29.

FILE Aug. 6, 1945: Photo released by the U.S. Army, a mushroom cloud billows about one hour after an atomic bomb was detonated above Hiroshima, western Japan. (AP Photo/U.S. Army via Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, HO)

It was time to try the atomic bomb. Truman’s science advisers told him a demonstration test of the bomb over a deserted island would serve no point – especially since only two atomic devices were ready – and recommended immediate use on an enemy target.

“We were about to be given a piece of ordnance which would far surpass any bomb ever dropped before by any nation,” recalled Gen. Curtis LeMay, who commanded B-29 bomber forces in 1945.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bombed Aug. 9, were chosen in part because they had not been firebombed. The unprecedented power of the A-bomb was clear.

The two atomic bombs, and the fear of more, gave Japan a reason to surrender.

“It was fortunate for both sides that Japan realized the wisdom of surrender,” concluded the U.S. Army’s official history and that the Allied plan carried out not invasion but “a peaceful occupation without gunfire, without further destruction, and without bloodshed.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Whatever one thinks of the factors Truman weighed, the judgment of history should now be added in. The use of the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki created a powerful nuclear deterrent widely credited with holding the Soviet Union and the West back from direct confrontation, aka World War III. Nuclear deterrence has been a bedrock strategy for every president since.

“I never thought of any regrets of being on that crew,” Caron said in 1985. “It was just a military mission we were picked to do.”