Someone in the government committed a serious crime. Indeed, it appears that several people did.

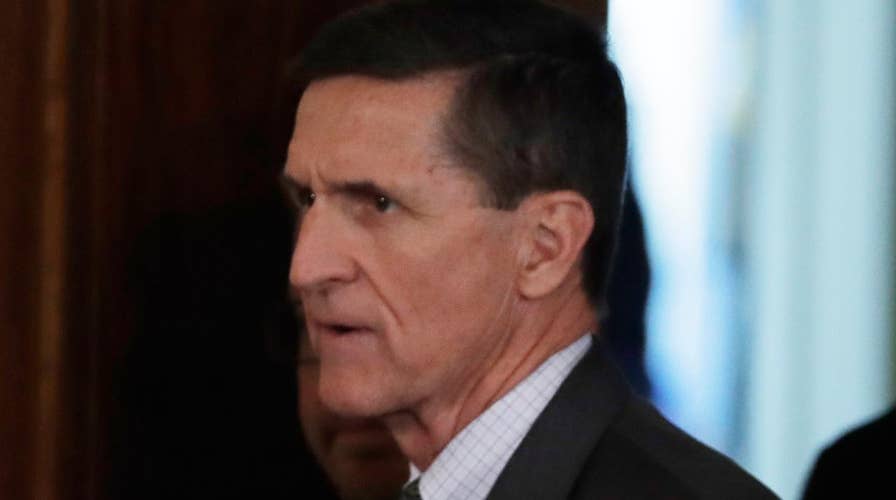

Those individuals had special access to the content of telephone conversations between President Trump's now former National Security Adviser Gen. Michael Flynn (ret.) and Russia’s Ambassador to the U.S., Sergey Kislyak. Those discussions were secretly recorded by American intelligence agencies. The tapes are classified documents.

Whoever conveyed the information contained therein to the Washington Post committed a felony. The Post reporter, David Ignatius, who published the classified material may also be prosecuted, but he should not be.

Prosecuting the Leakers

18 U.S.C. 798 states as follows:

“Whoever knowingly and willfully communicates…to an unauthorized person, or publishes…any classified information obtained by the processes of communication intelligence from the communications of any foreign government, knowing the same to have been obtained by such processes shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.”

It matters not that the leakers intended to reveal a deception by Flynn. The law’s intent clause refers only to the intent to reveal. Any underlying motivation to serve the public good by disclosing a lie or misrepresentation is of no legal consequence under the statute.

Ignatius describes the person who first told him of Flynn’s recorded discussions with Kislyak as “a senior U.S. government official.” That person committed the crime stated above.

But we discovered that others were also engaged in the same criminal activity when the reporter revealed, in a subsequent story, that the conversations were corroborated by “nine current and former officials, who were in senior positions at multiple agencies at the time of the calls” and who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss intelligence matters.

The only question now is the identities of any or all those individuals. Who had access? It could be a large group.

The collection of signals transmitted from communications systems as “signals intelligence” is known by the acronym SIGINT. The National Security Agency collects and analyzes the information. But any of the 16 other agencies that make up the U.S. intelligence community may have gained access to the Flynn-Kislyak conversations. Many of them likely did, given Ignatius’s reference to “multiple agencies” as his sources.

Prosecuting the Reporter

The law draws little distinction between the leakers and the recipient who publishes the classified information. Assuming the leakers will not reveal themselves, the government may feel it has no choice but to prosecute the only person whose name is known. That is, the reporter.

This would be a mistake. While the statute itself clearly criminalizes the publishing of classified material, the First Amendment should and must render that portion of the law unconstitutional as it applies to a journalist. The Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press…”. Just because Congress made such a law does not mean it can survive constitutional challenge.

The Framers well knew that a free press is a cherished cornerstone in any democracy. It is the only real way to hold government officials accountable for their actions.

In the famous 1971 “Pentagon Papers” case (New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713), Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black wrote that even the publication of government secrets should be immune from prosecution because that is precisely what the Founding fathers intended: “The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

Recognizing that prosecuting a reporter is arguably unconstitutional, the Department of Justice may try a different approach by serving a warrant or subpoena on Ignatius, hoping to pressure him into revealing his confidential sources. He will then likely invoke a reporter privilege which will invariably trigger a similar courtroom confrontation over constitutional rights involving the First Amendment. Previous cases have produced mixed results, although some journalists have been jailed over civil contempt charges.

It may seem unfair for the leaker of classified information to be prosecuted, while the reporter enjoys the protections of the First Amendment. However, the “Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act” sets forth clear procedures for intelligence officials to report complaints to Congress about serious problems involving intel activities. Because the leakers in this case did not utilize the law, they can be prosecuted for violating it.

The government should aggressively exercise its immense resources to determine who leaked the classified information contained in the Flynn-Kislyak conversations. Those individuals should be prosecuted as the law demands.

However, pursuing a reporter for his reporting, as encouraged by the Constitution, would be wrong.