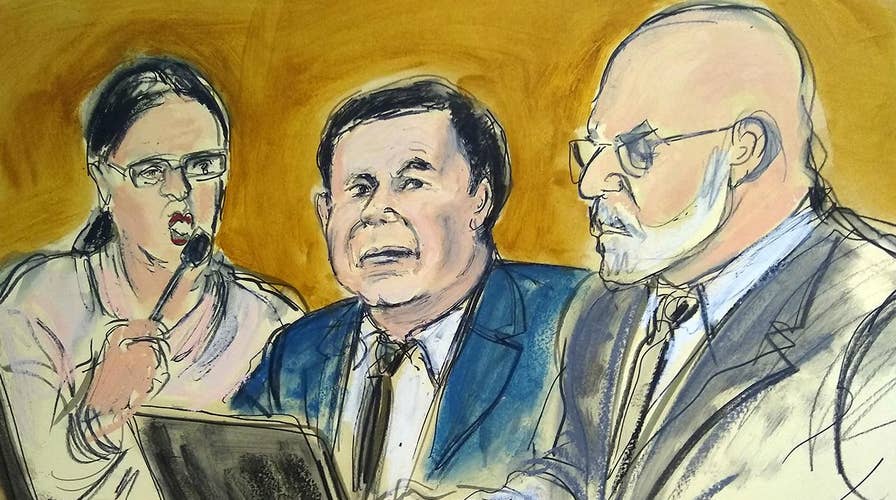

Jury reaches verdict in trial of Mexican drug lord Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman

El Chapo faces 10 separate counts and life in prison; Bryan Llenas reports from Brooklyn, New York.

The trial of Mexican drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman – who was found guilty Tuesday in federal court in New York City of running a drug smuggling operation and is guaranteed a sentence of life in prison – is a reminder of how important law enforcement operations and intelligence sharing are in combatting drug cartels.

The drug trafficking organizations based in Mexico are increasingly operating like terrorist networks at a time when U.S.-Mexican relations are anything but smooth.

Despite some alarmist warnings, the threat of major Islamist terrorist groups linking up with Mexican drug cartels remains minimal.

The cartels are money-making enterprises. Their leaders know that if a rogue Hezbollah cell or an ISIS-affiliated group tried to link up with them, it would only attract immediate U.S. attention – and likely, drones like the ones used to locate Guzman, leading to his arrest, and military coordination between Mexico and the U.S.

The takeaway: the drug cartel leaders are highly unlikely to risk damaging their multimillion-dollar business by linking up with some deranged or ideologically driven terrorist group.

But that doesn’t mean the drug cartels aren’t capable of terrorism themselves. One piece of evidence that wasn’t used in the Guzman trial – because prosecutors were not seeking a narco-terrorism conviction – was testimony showing that he and his cohorts once considered blowing up a news organization’s office or consulate.

At the time, U.S. law enforcement agencies and their Mexican counterparts were putting intense pressure on the Sinaloa cartel that Guzman helped lead.

“Yeah, it would be good to do it in the smoke (a nickname for Mexico City)," Guzman said of a bombing, according to testimony later submitted in a cartel trial in Chicago. "At least we’ll get something good out of it and Arturo (Beltran-Leyva, a crony-turned-enemy) will get the heat. Let it be a government building, it doesn’t matter whose. An embassy or a consulate, a media outlet or television station.”

Guzman’s alleged choice of action was more reactive than offensive, but terrorism nonetheless. Other attacks in recent years and the use of rocket-propelled grenades have also indicated the drug cartels are more willing to go on the offensive and use terrorist tactics to intimidate both the local population and the authorities.

“Nobody in America can tell me these are not ruthless terrorists,” one former U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration official told me during the Guzman trial.

Importantly, the Guzman trial revealed how deep the informant system of the DEA reaches, thanks to cooperating witnesses who have been working for the U.S. government for several years and came forward to testify, along with other information provided by law enforcement witnesses that came from their network of informants.

Cooperating witnesses and informants are not the same, but they are part of the same system.

The DEA has come under fire by the Justice Department in audits in recent years. DEA officials have been criticized for overpayments and poor oversight of people who are, effectively, criminals-for-hire and often serial liars.

But the DEA has shown the value of playing the long game of turning cartel members against each other to bring kingpins like Guzman to justice.

Going after the top cartel bosses has proven controversial – it has not reduced violence and in some cases, may have escalated the killings. Current Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has announced he will get rid of the strategy – but it has served a purpose, and hopefully the more successful elements will be integrated into any new strategy.

Critics of international wiretapping will have a field day with some of the testimony from the Guzman trial. However, advocates of wiretapping will likely point to one fact as evidence of its success: U.S. and Mexican law enforcement officials got Guzman thanks to text messages between him and his wife and mistresses, obtained with the help of an IT employee who flipped and cooperated with them.

When Guzman escaped prison in 2015, authorities got him again a year after. The more refined intelligence-gathering techniques and technologies become, the quicker fugitives like Guzman will be caught in future.

The importance of intelligence-sharing and international collaboration in an increasingly unpopular war on drugs was a key point that was perhaps not emphasized enough in the Guzman trial. Law enforcement agents who testified all owed a huge debt to the country in which they were operating. The trial also revealed how prickly these relationships can be.

One former Mexican intelligence official, speaking on condition of anonymity because he no longer represents the government, said the majority of U.S.-Mexico cooperation has always been strong, particularly between DEA and Mexican counterparts. But he said he was particularly irritated by evidence at the Guzman trial showing a DEA agent wearing a Mexican military uniform and carrying a weapon during the 2014 capture of Guzman.

“I had heard a few rumors that DEA were going around carrying weapons and sometimes even embedded in the Army and Navy,” he said, “(but) I never saw it happening or had a reliable account of it happening. I think it’s plain wrong. It shows little regard for Mexican law, the Mexican military, and the professionalism of our (military and police) forces. They (DEA agents) know they cannot carry guns, they showed very little regard for the law. That shows they think we’re inferior – that the laws in our country are not as important as the laws where they are from.”

Smoothing over such disputes and other problems revealed in the Guzman trial will be crucial, particularly at this increasingly important time in U.S.-Mexican relations.

President Trump’s xenophobic rhetoric towards Mexico has no doubt riled up some very important Mexican law enforcement counterparts who work with DEA and are vetted by U.S. agencies after receiving training.

Mike Vigil, a former DEA chief of international operations who is Hispanic and worked in Mexico during his career, has told me several times that President Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric is a disaster for U.S.-Mexican relations.

But several other ex-DEA agents have told me they welcome Trump’s pro-law enforcement talk after so many years of their agency getting attacked from all sides. However, they questioned Trump’s true intentions and loyalty after he fired Acting Attorney General Sally Yates and FBI Director James Comey.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

One thing is certain: the Guzman trial has shown that if the U.S. and Mexico are going to continue fighting the drug war, a metaphorical or literal wall that separates them won’t help.

Instead, success will require a continuation of the international cooperation and intelligence sharing that finally brought Guzman in front of a jury. This will carry the U.S.-Mexico relationship forward for the benefit of both countries.