The risk of CTE brain disease divides football and medical communities

Is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) a serious medical condition or an excuse for bad behavior? This is the question dividing the football and medical communities. Here is what you need to know about the disease.

Football. Drugs. Aggression. Murder. Jail. Suicide.

How much of ex-NFL player Aaron Hernandez’s troubled life stemmed from the brain injury chronic traumatic encephalopathy, known simply as CTE?

The question has been re-ignited on the heels of the hit Netflix documentary “Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez,” with medical experts, players, parents and sporting bodies purporting to understand the still mysterious – and highly controversial – condition.

How much of a cause for concern is it really?

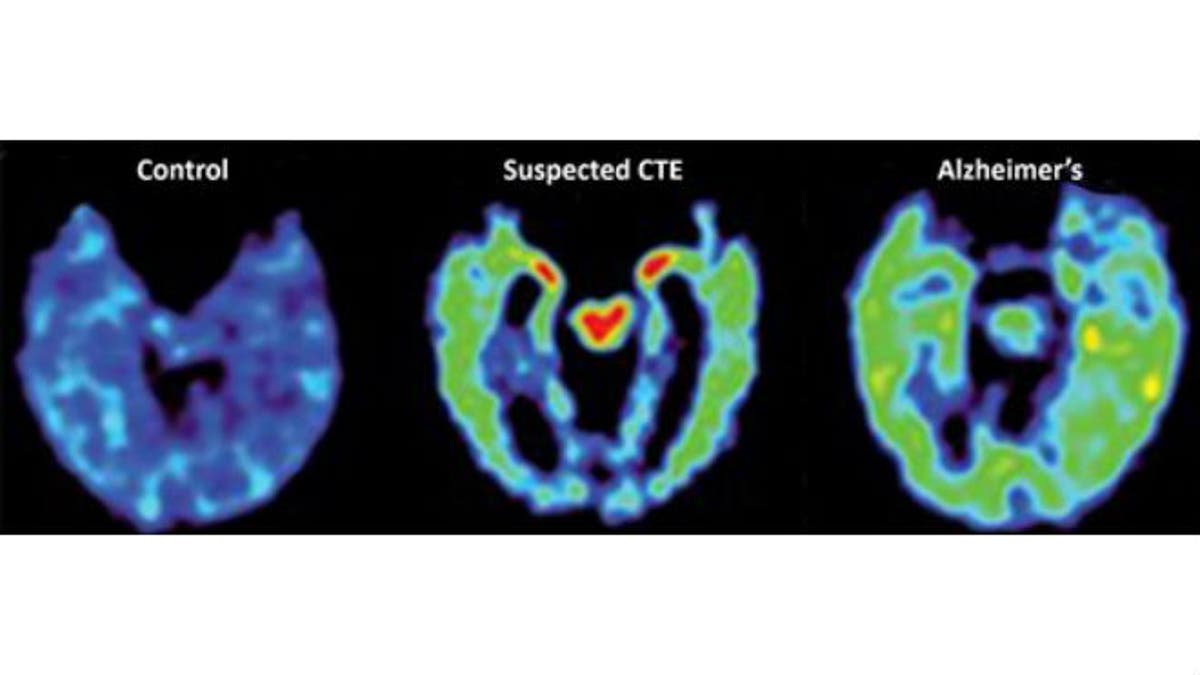

“CTE is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that shares characteristics with Alzheimer’s disease. The major differences between those two diseases is how they begin, the location of the initial brain lesions, and pattern of progression, and the clinical symptoms that result,” Chris Nowinski, co-founder and CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, told Fox News. “CTE is very rare in the overall population, but it is clearly prevalent in populations with significant exposure to brain trauma.”

Dec. 10, 2012: New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez reacts during the second quarter of an NFL football game against the Houston Texans in Foxborough, Mass. State and local police spent hours at the home of New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez on Tuesday June 18, 2013 as another group of officers searched an industrial park about a mile away where a body was discovered the day before. (AP Photo/Elise Amendola)

While often associated with football, CTE was first recognized in the 1920s as “punch drunk syndrome” in boxers. Since then, it has expanded to raise red flags around a myriad of other sports including soccer, rugby, horse racing, bull-riding, skiing/snowboarding, hockey, and wrestling.

Medical researchers now believe CTE is caused by an accumulation of apparent tau proteins in the brain – which can impair neuro-pathways.

“Cells start to die and the brain starts to shrink, causing memory problems and trouble living your daily life, and problems with behavior, specifically outbursts of violence,” explained Michael L. Alosco, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the Boston University School of Medicine, which has pioneered much of the CTE research over the past 12 years. “But we are trying to get a better sense of what this disease looks like in life.”

Michael Alosco, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the Boston University School of Medicine (Fox News/Hollie McKay)

Yet it is a condition where there are seemingly more unknowns than there are knowns.

As it stands, there is no accurate mechanism for detecting abnormal tau abrasions in a living person. It’s only after death, in an autopsy, that such an abnormality can be identified. Moreover, scientists are still in the process of determining what specific genetic markers make one person must prone to CTE than another person, irrespective of the number of knocks and head traumas. And many of the indicia can be attributed to other neurological diseases.

FAMILY MURDER SUICIDES IN YEMEN HIGHLIGHT DEPTHS OF WAR-INDUCED MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS

The biggest advancement, Alosco highlighted, that they are working toward is a “tau tracer” that could be effective on a live patient.

“CTE has only recently been recognized. Whenever a new disorder or pathology is identified or suggested, there is much research to understand the causative or contributing factors, pathological processes, clinical diagnosis, lab tests, and imaging,” observed Dr. Joseph Horrigan of the Southern California University of Health Sciences. “(But) the symptoms of those who develop what we label as CTE should be alarming. We are seeing athletes with outstanding physical and mental capabilities become reduced to patients with cognitive deficits, memory loss, irritability and aggression, impulse control issues, mood changes and in some cases suicide. These symptoms are occurring at a younger age than we would normally expect.”

Alosco said that Hernandez, who was 27 when he died behind bars almost three years ago, had a “pretty advanced disease,” but the youngest case he can recall was that of a 24-year-old. Boston University currently has one of the largest brain banks in the world, its researchers have analyzed more than 650 brains of a wide age range in the endeavor to establish a CTE consensus.

This combination of PET scans provided by UCLA on April 2, 2015 shows, from left, a normal brain scan, a suspected Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) subject, and a subject with Alzheimer's disease. (AP Photo/PNAS/David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA)

And there has been no shortage of lawsuits surrounding the alleged prevalence of CTE. In 2011, almost 5000 retired players collectively sued the NFL claiming long-term neurocognitive diseases that could be connected to CTE, ending in a $1 billion agreement for a longstanding compensation fund to aid former players and their families.

In 2018, 53 former professional wrestlers accused World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) of masking the threat of head injuries. The suit was subsequently dismissed and is not on appeal. That same year, more than 300 players joined the multidistrict litigation against the National Hockey League (NHL) regarding neurological woes. And in August last year, an Illinois federal judge approved a $75 million settlement between the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and millions of student-athletes to monitor concussion symptoms.

The likes of Paul Wood, 38, a former professional rugby league player in the U.K. is already prepared for his symptoms to start worsening.

“I sustained substantial head impacts most games and during training on a regular basis which today I feel certainly contributes to my memory loss, mood swings and lack of concentration,” he noted, underscoring that such symptoms have become more pronounced since retiring in 2018. “I had numerous concussions but the nature of our environment meant I always wanted to keep training or playing, even with headaches.”

Wood underscored that the subject of CTE is especially worrisome given that “rugby league is a high-impact sport,” and that he didn’t wear protection. However, experts say that headgear makes little difference when it comes to this particular purported disease.

“I don’t think (headgear) is going to make all that much difference when it comes to CTE,” said Alosco. “Headgear is meant to stop skull fractures, not stop the brain from moving.”

From Nowinski’s lens, “our society needs to have a serious discussion about preventing and learning how to treat CTE.”

“Three million children currently play tackle football, and our research has shown that their odds of developing CTE increase by 30 percent each year they play,” he continued. “Those individuals began playing football as children, most of the exposure happened before the age of 18, meaning before the age of consent. We need to change how we play sports.”

Kansas City Chiefs' Bashaud Breeland (21) reacts against the San Francisco 49ers during the first half of the NFL Super Bowl 54 football game Sunday, Feb. 2, 2020, in Miami Gardens, Fla. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Such changes, he pointed out, entail “in football, reducing contact in practice, in soccer limiting exposure to headers,” and in baseball introducing limits as to “how many times you can hit an athlete in the head.”

But certainly, not everyone will develop protracted neurological issues either during their playing days or in the decades that come after. The lack of definitive answers – as of yet – has turned CTE into an especially decisive issue across the country.

New Jersey native Anthony Patanella, 38, said he has suffered more concussions in his two-decade career as a professional boxer than he can count – and said more needs to be done from the top to minimize CTE risks.

“They can stop fights sooner if the fighter is taking too many punches and not punching back or moving his head to avoid taking hits,” he said. “I’ve seen other fights with (evident) brain damage, slurring their words, and it is sad. (Too many blows) can affect you in the long haul, and then it is too late.”

Anthony Patanella, 38, said he has suffered more concussions in his two-decade career as a professional boxer than he can count – and said more needs to be done from the top to minimize CTE risks. (Courtesy Anthony Patanella)

Yet Merril Hoge, a former running back for the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers and Chicago Bears later turned ESPN analyst, has been one of the most outspoken critics against the alarm surrounding CTE studies – putting much of the research down to “science fiction” and “misleading” science far from a factual realm. In 2018, he co-authored the controversial book “Brainwashed: The Bad Science Behind CTE and the Plot to Destroy Football” with Dr. Peters Cummings, an assistant neurobiology professor at BU, essentially rejected much of the “unfounded” hype.

“It is easier to fool people than to convince them they have been fooled. Concussion and TBI (traumatic brain injury) are real, but there is no connection between this and CTE,” Hoge lamented, stressing that “CTE” has too often become something of an excuse for poor behavioral patterns in later life.

He also underscored that, from his lens, demonizing sports like football does more harm to American children than good.

“The leading cause of brain disease is obesity. We have kids rotting in front of our eyes from sugar and inactivity, and now we want to create a corrupt narrative for them not to play,” Hoge conjectured. “With all the head trauma protocol and treatments we have available today, we have the best environment for our kids to be playing in the history of sports.”

XFL RULES TO IMPACT COLLEGE FOOTBALL TEAM'S SPRING GAME

For its part, the NFL has continued to back government-funded research on the issue as part of its “Play Smart. Play Safe” initiative and has allocated $40 million toward medical research primarily devoted to neuroscience.

Dec 15, 2013; Miami Gardens, FL, ESPN analyst Merril Hoge looks on before a game against between the New England Patriots and the Miami Dolphins at Sun Life Stadium. The Dolphins won 24-20. Mandatory Credit: Steve Mitchell-USA TODAY Sports

“Important research advancements have been made over the last several years around traumatic brain injury (TBIs). Close attention needs to be paid to these research findings and collectively the research community must work together,” Dr. Sills, the Chief Medical Officer of the NFL, told Fox News. “While we don’t have all the answers, the NFL has been a leader on player health and safety including implementing data-driven rules changes that aim to help eliminate potentially risky behavior that could lead to injuries, especially to the head and neck; and instituting a concussion protocol reflecting the most up-to-date medical consensus on the identification, diagnosis, and treatment of concussions.”

Sills stressed that the NFL is furthermore providing sideline medical support that includes unaffiliated medical personnel and new technology to assist in the identification and review of injuries, with a specific focus on concussions; mandating ongoing health and safety education for players and training for club and non-affiliated medical personnel; developing mandatory guidelines on protective equipment; enforcing limits on contact practice; and advancing developments in engineering, biomechanics, advanced sensors, and materials science that mitigate forces and better protect against injuries in contact sports and recreational sports.

So where to go from here?

Anthony Trucks, a former player for the Washington Redskins and Pittsburgh Steelers who retiring just over a decade ago said that while he does have some concerns, he thinks the alarm has largely been “blown out of proportion.”

“If you were ever going to play, now is the safest time,” he said. “And there are many benefits to the game. I want my kids to go to practice, and competition is great for humanity.”

Indeed, for many professionals, the benefits of the game far outweigh the cons.

“Would I play again for 17 years? Even though I know it has had an impact on my brain?” Wood added. “The answer is yes. I would do it all over again.”