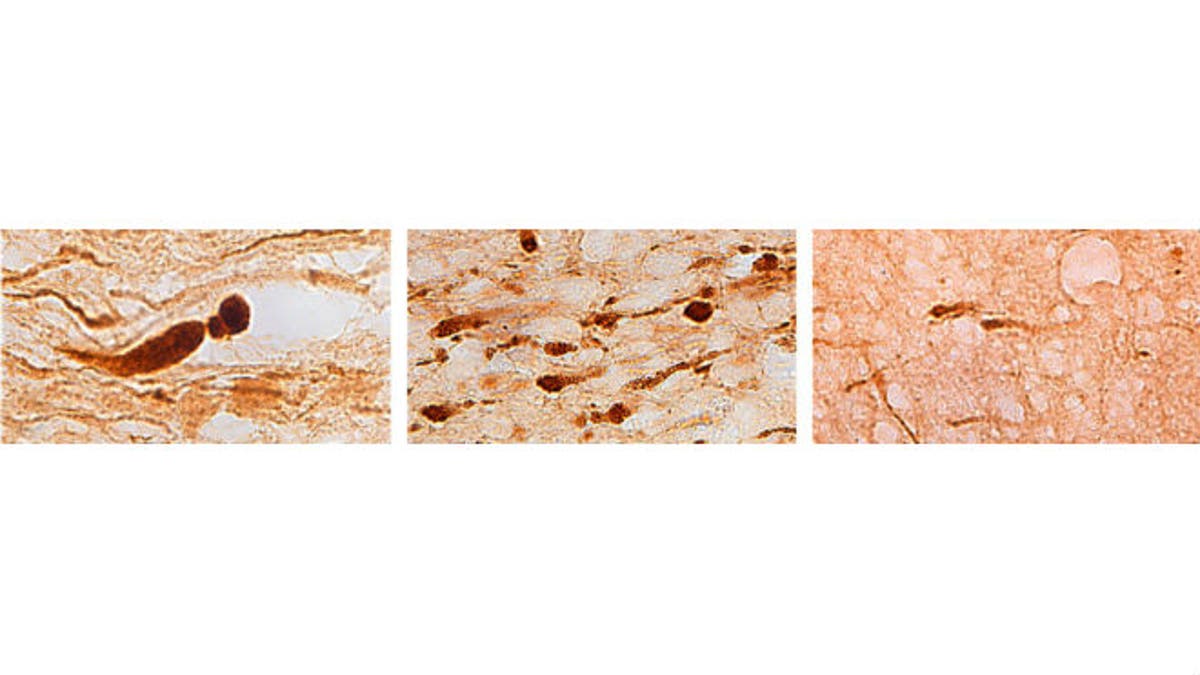

Brain sections from three different individuals show (left) axons with large, bulb-shaped lesions characteristic of a motor vehicle crash; (center) many smaller lesions characteristic of a blast injury; and (right) fewer lesions characteristic of an opiate overdose. (Credit: Vassilis Koliatsos)

New research shows that veterans who survived explosive blasts have distinct brain changes, suggesting that these impacts may be to blame for many of the psychological and social problems that vets face upon returning home.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine examined the brains of five male U.S. military veterans, ages 23 to 28. All subjects had survived improvised explosive device (IED) attacks but later died of other causes, including methadone overdoses that may have been accidental. The drug is commonly prescribed for soldiers’ chronic pain, a gunshot wound to the head, and multiple organ failure. The veterans’ brains were compared to those of 24 people who died from a range of causes including heart attacks and motor vehicle crashes.

Using a molecular marker, researchers tracked a protein called APP as it traveled from one nerve cell to another by an axon, a long nerve fiber. If axons are broken by injury, APP and other proteins clump at the break and cause swelling.

Researchers found that axonal swellings look differently, depending on the injury. In the brain of a death caused by a car accident, the swellings are large and bulb-shaped. In those that died of methadone overdose, the swellings are small.

Looking at the brains of the vets, in four of the vie, researchers found that the axonal bulbs were medium-sized and arranged in an unusual, specific honeycomb pattern near blood vessels.

“We identified a pattern of tiny wounds, or lesions, that we think may be the signature of blast injury. The location and extent of these lesions may help explain why some veterans who survive IED attacks have problems putting their lives back together,” senior study author Dr. Vassilis Koliatsos, a professor of pathology, neurology, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, said in a press release.

Researchers did not find signs of the neurodegenerative disease known as punch-drunk syndrome— which is caused by multiple concussions— but did observe specialized cells near the damaged axons. These microglia cells are involved in brain inflammation.

Additionally, the distinctive lesions were found in a number of places in the veterans’ brains, including the frontal lobes, the region responsible for decision making, memory, reasoning, and other executive functions. Researchers believe the lesions could be fragments of nerve fibers that broke at the time of the blast and slowly deteriorated or that they may have been weakened by the blast and later were broken by some later insult like a concussion or drug overdose.

“When you look at a brain, you are looking at the life history of an individual who may have a history of blasts, fighting, substance abuse or all of those,” Koliatsos said in the press release. “If researchers could study survivors’ brains at different times after a blast — a week, a month, six months, one year, three years —that would be a significant step forward in figuring out what actually happens over time after a blast.”

Researchers noted that IED survivors are often treated for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, substance abuse, and adjustment disorders and that their findings should provide background for future work in understanding blast neurotrauma and its effects.

“It’s important to understand that at least a portion of these difficulties may have a neurological foundation,” he said.

The research was published in November 2014 in Acta Neuropathologica Communications.