(Quirk Books)

There are great pairings - Adam and Eve, Antony and Cleopatra, Gumby and Pokey - and then there are sublime ones - Linguine alle Vongole, Tortellini con Panna, Orechiette con Cime de Rapa. But switch them around - orechiette in cream, tortellini with clam sauce, linguine with broccoli rabe - and you end up with dishes that should never exist.

Pairing the right pasta with the right sauce is intuitive for Italians. “It’s their birthright,” says designer and author, (Caroline) Caz Hildebrand, who, along with co-author Jacob Kennedy, has attempted to decipher the code in their new book, “The Geometry of Pasta.”

The cookbook uses history, geography, agriculture, texture, mouth feel and graphic design to explain which pastas go with which sauces and why. Besides familiar standbys like ravioli and lasagna, there’s corzetti, embossed with fruitwood stamps; tortiglioni, small diagonally-grooved tubes; and torchio, torched-shaped pasta for which Kennedy whipped up a meaty bone marrow and tomato sauce that’s “not for the faint-hearted or those at risk of a heart attack.”

Other examples of pasta arcana include strozzapreti - Italian for “priest stranglers,” whose name was inspired by priests who ate them so eagerly that they were apt to choke- and garganelli, thin, rolled, concentrically-ribbed tubes, which look exactly like their namesake. Garganel means esophagus in Emilia-Romagna.

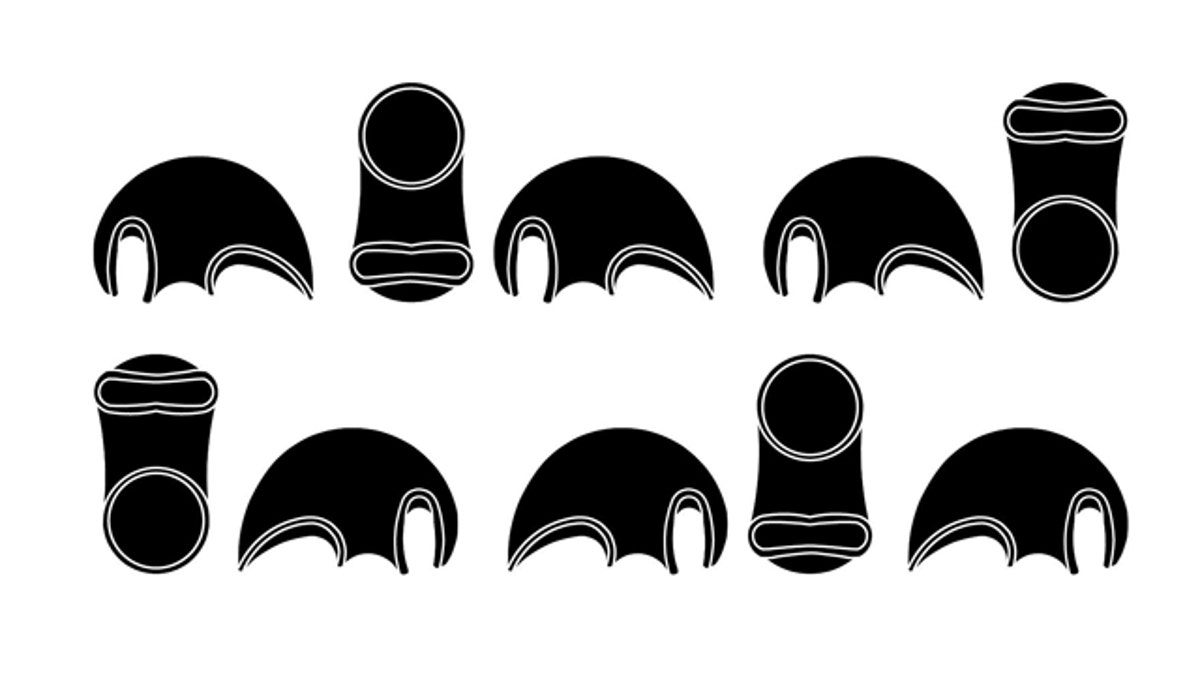

For Hildebrand the interest started with a poster for plumbing grommets, “one of those things with black, silhouetted shapes of rubber sealers,” she says. It struck her, “as a great way to communicate about shapes.” You didn’t need to know the code number for the one you wanted, you just had to look at the shapes, she says. That became the book’s visual standard and explains why “The Geometry of Pasta” looks as much like Op-Art as a cookbook.

Chic graphic black and white illustrations give it the feeling of a hip industrial design manual. “I think a book of 150 photos of plates of pasta would be very boring,” says Hildebrand, who feels that cookbook photography can set people up to fail. “It’s hard to achieve what you see in a photograph.” Illustrations appeal to and free the imagination. Most are instantly understandable like penne and conchiglie (shells). Others like canederli, a golf-ball sized bread, egg, butter, onion and pancetta dumpling from Italy’s Alpine region, take a little more effort.

There are about 300 different types of pasta, she says, and around 1200 names, “the triumph of hope over experience,” she jokes. “If you’re Italian, you just know by osmosis which pastas go with which sauce.” No self-respecting Italian would ever eat Spaghetti Bolognese or Vongole with Penne. Says Hildebrand, “there were rules and I wanted to understand them.”

Jacob Kennedy, chef and owner of Bocca di Lupo, one of London’s top eateries, developed the book’s recipes by, “spending a year traveling in Italy and eating like an absolute pig. I learned a fair bit there,” he says. It was like old times. Kennedy’s mother was raised in Italy; he summered there and speaks Italian like a native. His most basic rule-of-thumb: pasta from a region is good with sauce from that region.

Fish flavors go with smooth-textured pasta like linguine or pacchieri - huge, hollow, tubes that unlike manicotti are never stuffed. Ridged pastas like rigatoni grasp hearty sauces well. Chunky sauces are good with tightly-spiraled, torpedo-shaped trofie. Soup requires pastinas - small pastas, like quadrettini or riso. Heavy, thick sauces go perfectly with a filled-pasta like angolott - veal, pork and sage-stuffed semi-circles. Think: delicate pasta, light sauce; heavier pasta, thicker sauce.

Kennedy recommends eating thick, rustic, “pre-industrial” pastas like bucatini (a spaghetti-sized hollow tube) and cavatelli when made from fresh, not dried, pasta due to their density. “By the time the inside is beginning to cook the outer surface edges will have turned to mush. If you can’t get it fresh don’t eat it at all,” he recommends. Later pastas reflected Italy’s love of design, and have a decidedly industrial esthetic: eliche (“screws”) and fusilli (“spindles”); gomiti (“crank shafts”); lancette (“clock hands”); trivelli (“drills”) and radiatore (“radiators.”)

While Kennedy recreated classic sauces for most recipes, certain shapes inspired new creations like a “warming” red pepper and whiskey sauce for radiatore, and Lumache alle Lumache, snail-shell shaped pasta with snail sauce. There’s the pureed greenbean, cream and cinnamon sauce for green bean-sized gemelli, and “Frankfurter and Fontina Sauce” for ruote (“wheels”) with directions to fry the frankfurters in butter until they start to brown and “smell like a hotdog stand.”

Despite the rules it lays out, you come away from The Geometry of Pasta feeling that pairing pastas with sauces will always be best understood intuitively. Take dischi volanti (“flying saucers.”) James Bond fans will see them and remember that Thunderball villain Emilio Largo named his ship the “Disco Volante.” Others will see them as little alien spaceships. Kennedy sees them as the perfect vehicle for an oyster, Prosecco and tarragon sauce. “My feeling is that anything in the world worth cooking can be the most delicious thing in the world if cooked with a good hand, understanding and love.”

Even UFOs.